Antifragile Food Systems

"The alpha person at a gathering of "high

status" persons is usually the waiter.

"

In the film, No Escape, Owen Wilson and Lake Bell's

characters play a stereotypical USAnian couple, Jack and Annie Dwyer, cast

abroad like fishes out of water. He is a corporate engineer in charge of

putting a water plant into a fictional Southeast Asian country. She is the

dutiful wife, bringing along to the temporary assignment two young children and

their favorite kitchen appliances.

In the film, No Escape, Owen Wilson and Lake Bell's

characters play a stereotypical USAnian couple, Jack and Annie Dwyer, cast

abroad like fishes out of water. He is a corporate engineer in charge of

putting a water plant into a fictional Southeast Asian country. She is the

dutiful wife, bringing along to the temporary assignment two young children and

their favorite kitchen appliances.

In Antifragile: Things that Gain from Disorder, Nassim Nicholas Taleb

distinguishes antifragile from words like robust or resilient by saying that

when something is antifragile, it benefits when things go bad. Taleb is a

recovering Wall Street quant trader. He understands hedges and shorts, and

indeed, wrote the textbook on dynamic hedging in 1997. His subsequent books, Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of

Chance in Life and in the Markets (2001) and The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (2007)

redefined at how traders look at risk and how people should think about risk in

life choices.

In Antifragile: Things that Gain from Disorder, Nassim Nicholas Taleb

distinguishes antifragile from words like robust or resilient by saying that

when something is antifragile, it benefits when things go bad. Taleb is a

recovering Wall Street quant trader. He understands hedges and shorts, and

indeed, wrote the textbook on dynamic hedging in 1997. His subsequent books, Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of

Chance in Life and in the Markets (2001) and The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (2007)

redefined at how traders look at risk and how people should think about risk in

life choices.

Those who study the evolution of

consciousness suggest that the shift may have occurred, with or without sacred

plant intervention, about 10 millennia ago when the brain had a hundredth

monkey moment and, like Kubrick's apes before the shiny monolith, transformed

bone shillelaghs into plows and space stations.

Those who study the evolution of

consciousness suggest that the shift may have occurred, with or without sacred

plant intervention, about 10 millennia ago when the brain had a hundredth

monkey moment and, like Kubrick's apes before the shiny monolith, transformed

bone shillelaghs into plows and space stations.

In the 1960s, "a picture began to emerge that showed that foraging communities were able

to remain in equilibrium at carrying capacity when undisturbed." Where the

ratio of population to productive land area is favorable, foraging generally

provides greater return on labor invested than tilling and herding. Once the

ratio becomes unfavorable, tilling and herding are not only more effective, but

necessary. To any foraging society, therefore, two disciplines are required.

They must regenerate land resource and restrain population growth. Soil

fertility sí, human fertility no.

In the 1960s, "a picture began to emerge that showed that foraging communities were able

to remain in equilibrium at carrying capacity when undisturbed." Where the

ratio of population to productive land area is favorable, foraging generally

provides greater return on labor invested than tilling and herding. Once the

ratio becomes unfavorable, tilling and herding are not only more effective, but

necessary. To any foraging society, therefore, two disciplines are required.

They must regenerate land resource and restrain population growth. Soil

fertility sí, human fertility no.

In permaculture, we speak

of harmony and stress and some see those as opposites, but in a more tantric Buddhist interpretation they can be viewed as a symbiotic pair. Stress is the bending of a system

away from its natural pattern, making it fragile. Harmony is the restoration of

balance and connections, inherently antifragile. Natural succession is a cycle

of disturbance, experimentation, and equilibrium. There is no steady state,

there is only the constancy of change.

In permaculture, we speak

of harmony and stress and some see those as opposites, but in a more tantric Buddhist interpretation they can be viewed as a symbiotic pair. Stress is the bending of a system

away from its natural pattern, making it fragile. Harmony is the restoration of

balance and connections, inherently antifragile. Natural succession is a cycle

of disturbance, experimentation, and equilibrium. There is no steady state,

there is only the constancy of change.

In the film, No Escape, Owen Wilson and Lake Bell's

characters play a stereotypical USAnian couple, Jack and Annie Dwyer, cast

abroad like fishes out of water. He is a corporate engineer in charge of

putting a water plant into a fictional Southeast Asian country. She is the

dutiful wife, bringing along to the temporary assignment two young children and

their favorite kitchen appliances.

In the film, No Escape, Owen Wilson and Lake Bell's

characters play a stereotypical USAnian couple, Jack and Annie Dwyer, cast

abroad like fishes out of water. He is a corporate engineer in charge of

putting a water plant into a fictional Southeast Asian country. She is the

dutiful wife, bringing along to the temporary assignment two young children and

their favorite kitchen appliances.

When civil war suddenly

erupts before they have even gotten past jet-lag and they find themselves in an

urban killing field, hunted by machete-wielding guerillas who are really angry

about the way Jack's corporation has stolen and monetized their water rights,

they must run for their lives, which they do for the next hour or more of

screen time.

That's the plot, but the

film is less about why the couple got into their predicament or why this small

country has decided to murder all its foreign tourists than how Jack and Annie

and their children absorb the changed circumstances, adapt to their precarious

situation, and do what it takes to survive. Theater audiences are rooting for

them, despite their complete lack of preparation.

In Antifragile: Things that Gain from Disorder, Nassim Nicholas Taleb

distinguishes antifragile from words like robust or resilient by saying that

when something is antifragile, it benefits when things go bad. Taleb is a

recovering Wall Street quant trader. He understands hedges and shorts, and

indeed, wrote the textbook on dynamic hedging in 1997. His subsequent books, Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of

Chance in Life and in the Markets (2001) and The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (2007)

redefined at how traders look at risk and how people should think about risk in

life choices.

In Antifragile: Things that Gain from Disorder, Nassim Nicholas Taleb

distinguishes antifragile from words like robust or resilient by saying that

when something is antifragile, it benefits when things go bad. Taleb is a

recovering Wall Street quant trader. He understands hedges and shorts, and

indeed, wrote the textbook on dynamic hedging in 1997. His subsequent books, Fooled by Randomness: The Hidden Role of

Chance in Life and in the Markets (2001) and The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable (2007)

redefined at how traders look at risk and how people should think about risk in

life choices.

If Jack and Annie had read

either Fooled by Randomness or The Black Swan, they would not have been

thrown into such profound stupor when the country they had landed in suddenly

dissolved into anarchy and savage brutality. These things, or equally

unpredictable things, are to be expected, even predicted.

Antifragile goes a step

beyond and asks how one can be prepared to benefit from Black Swan events.

Taleb gives the example of biological and economic systems. Efficiency and

optimization are the final stages of succession — a mature ecology. They

are also fragile. Inefficient redundancy is robust. Degeneracy is antifragile.

The early sere following some disturbance is filled with fast-growing,

thick-stemmed "weeds" that require few soil nutrients or supporting

microbial diversity. If there is not much sun, too much wind or rain, poorly

suited pioneers will fall aside and those better selected will dominate.

Fragile systems hate

mistakes. Antifragile systems love them. Postmodern thinking, almost completely

divorced from nature, is built on a scaffold of prior delusions. Medieval Europe,

grounded in a theological storyline that is unwavering (like hard-core Evangelical

Christianity or Sunni Islam) is more robust. But the pre-European Mediterranean

seafaring cultures — pantheistic, surrounded by random dangers and ubiquitous

risk (pirates, police states, conscription, volcanoes) and utterly free

enterprise, was antifragile. People in that time exchanged rites and gods the

way we do ethnic foods. Like Silicon Valley, ideas and gods failed fast, failed

often, but occasionally winners emerged.

Taleb casts this into

mathematical metaphors: the fewer the gods the greater the dogma and higher the

risk of conflict and loss. For atheists n=0; Sunni purists n=1; monophysites

n=1-2; Greek Orthodoxy n=3-12; pagans, wiccans and most native peoples n=infinite.

Whose religion is more fragile and likely to occasion bad things happening?

Jack and Annie Dwyer are

in the fragile, corporate employment class. They are pampered. They did well in

school. They don't need to know a word of the language of the country they have

been sent to. They complain if there is no a/c in the room or the limo doesn't

arrive on time. They are intellectual tourists. Their antifragile counterpart

is a slacker — fläneur is the word Taleb uses — the creative loafer with a

large library or an X-box. Taleb says the alpha person at a gathering of

"high status" persons is usually the waiter.

Engineering and corporate

middle management are fragile professions. Financially robust professions in

the run-up to ponzicollapse would be dentists, dermatologists, or minimum wage

niche workers. Antifragile jobs in the overtopping and onset of decline are

payday check cashing tellers, taxi drivers and nomadic fishermen. The Roma,

living parasitically at the urban edges of European cities, are antifragile,

but have vulnerability to travel restrictions. When Sweden closed its border

crossings and started doing screening of incoming migrants, Denmark had to

follow or risk being swamped with migrants denied entry to Sweden. Holland,

Germany and France did the same. This is not a good thing for gypsies, but they

are resilient enough to make do with one country at a time and antifragile

enough to exploit weaknesses in border security and even turn that into new

opportunities and enterprises.

What is an antifragile

food system? This becomes especially important as we enter an era of rapid

climate change and civil disintegration. A decade ago in "From Foraging to

Farming, Explaining the Neolithic Revolution" (J Econ. Surveys 19:4:561-586, 2005), Jacob Weisdorf at the

University of Copenhagen reviewed the main theories about the

prehistoric shift from hunting and gathering to agriculture. The transition,

also known as the Neolithic Revolution, was necessary precursor for capitalism,

industrialization and the monotheistic religion of economic growth. Hunting and

foraging societies were egalitarian and communal. Farming and herding societies

are vested, competitive and hierarchical.

The Neolithic Revolution augured slavery, which began as agricultural serfdom and abides today as

the "jobs" system. Taleb opines that in the days of Suetonius, 60

percent of prominent educators (grammarians) were slaves. Today the ratio is

97.1 percent and growing.

Charles Darwin in The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication (1868)

said:

The savage inhabitants of each land, having found out by many and hard trials what plants where useful ... would after a time take the first step in cultivation by planting them near their usual abodes.... The next step in cultivation, and this would require but little forethought, would be to sow the seeds of useful plants.

Did it really take several million years

for our upright hominid ancestors to get the idea they could domesticate plants

and animals, or had they known that much longer and invariably decided it was a

bad idea?

One hypothesis is that the extinction of

large herding animals by Paleolithic hunters led to farming. This is discounted

by the fact that the loss of the former did not coincide with the gain of the

latter, either geographically or chronologically. Another theory is that we

were forced into farming by population pressure, but that is countered by the

fact that the first domestications took place in resource-abundant societies. Moreover,

dietary stress would have marked the skeletons of foragers and studies have

failed to show any nutritional stress immediately prior to plant domestication.

Another theory is that the rise of

agriculture came from ‘competitive feasting;’ the idea that culinary diversity

conferred social status and therefore resulted in competition to create

delicacies. Let's call this gourmetgenesis.

Unfortunately for foodie anthropologists, it appears that early domestication

unambiguously consisted of a small number of important staples rather than appetizers,

pastries and confections.

Those who study the evolution of

consciousness suggest that the shift may have occurred, with or without sacred

plant intervention, about 10 millennia ago when the brain had a hundredth

monkey moment and, like Kubrick's apes before the shiny monolith, transformed

bone shillelaghs into plows and space stations.

Those who study the evolution of

consciousness suggest that the shift may have occurred, with or without sacred

plant intervention, about 10 millennia ago when the brain had a hundredth

monkey moment and, like Kubrick's apes before the shiny monolith, transformed

bone shillelaghs into plows and space stations.

More recent work suggests that climate

shifts not only contributed to the Paleolithic large mammal extinctions and may

have caused psychedelic mushrooms, vines and cacti to extend their ranges and

abundancies, but also permitted more reliable predictions about weather,

which allowed crops to be grown more consistently.

Some ancient Greeks thought that this process

was cyclical, and that eventually good weather would lapse and we would return

to hunting and foraging. Medieval Christianity embedded the meme that the

process is linear, an inexorable progression of human civilization from

brutality to refinement.

Weisdorf notes:

Farming [is] still assumed to have been clearly preferable to foraging. But, in the 1960s, this perception was to be turned upside down. Evidence started to appear which suggested that early agriculture had cost farmers more trouble than it saved. Studies of present-day primitive societies indicated that farming was in fact backbreaking, time consuming, and labor intensive.

In the 1960s, "a picture began to emerge that showed that foraging communities were able

to remain in equilibrium at carrying capacity when undisturbed." Where the

ratio of population to productive land area is favorable, foraging generally

provides greater return on labor invested than tilling and herding. Once the

ratio becomes unfavorable, tilling and herding are not only more effective, but

necessary. To any foraging society, therefore, two disciplines are required.

They must regenerate land resource and restrain population growth. Soil

fertility sí, human fertility no.

In the 1960s, "a picture began to emerge that showed that foraging communities were able

to remain in equilibrium at carrying capacity when undisturbed." Where the

ratio of population to productive land area is favorable, foraging generally

provides greater return on labor invested than tilling and herding. Once the

ratio becomes unfavorable, tilling and herding are not only more effective, but

necessary. To any foraging society, therefore, two disciplines are required.

They must regenerate land resource and restrain population growth. Soil

fertility sí, human fertility no.

In Resilient Agriculture: Cultivating Food Systems in a Changing Climate

(New Society 2015), Laura

Lengnick gives her take on the progression from foraging to pastoralism to

agriculture:

Foraging and the early farming systems that followed it propose very different solutions to the same basic question facing all animals: How best to allocate the available time and resources to acquire food? All things being equal, animals (including humans) tend to solve this effort-allocation problem by maximizing the capture of calories, protein and other desired foods in a way that yields the most return with the greatest certainty in the least time for the least effort. Moderate, reliable returns are usually preferred over fluctuating high returns. It turns out that, for a long time, foraging was a good solution to the effort-allocation problem facing early humans. But climate change changed everything.

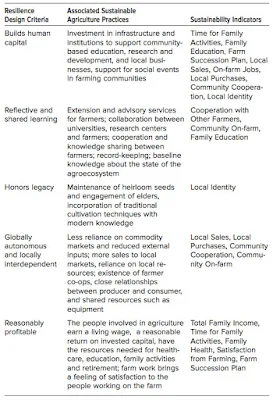

|

| Lengnick, Resilience Design Criteria for Agroecosystems |

Lengnick describes the

strategies employed by native peoples of North America. They foraged and

hunted, sustainably used irrigation, amended with fish scraps and animal manures as

fertilizers, rotated grain and legume crops and selected and improved their

seeds. She looks at the Mohawk, Cherokee, Mandan and Hohokam as representative

of the North American Northeast, Southeast, Northern Great Plains and

Southwest. She then turns to the practices brought by European colonists,

before and after the arrival of petroleum, modern machines and chemicals.

Regional specialization continues today, based more on industrial infrastructure

than soils or suitability, but climate has thrown in a monkey wrench, much the

way it did 8-12,000 years ago.

From the

summer of 2013 through late winter 2014, Lengnick interviewed 25 award-winning

sustainable producers from across the United States. All had been farming in

the same location for at least 20 years, many for 30 and some for 40 years or

more. Many expressed concerns about the path the food system has taken over the

last 50 years and their frustrations with scientific, economic and regulatory

policy. Listening to their stories is like sitting around a campfire with two

dozen Joel Salatins.

At the Happy Cow Creamery,

artisanal dairyman Tom Trantham told Lengnick,

Really, we see some drought and hot temperatures every year. This year (2013) is the first year that we haven’t really had a drought. This year it has been really wet. We had the rain, but we also didn’t have the sun, so we had two big problems. I’m 72 years old, and I’ve never seen as much rain in a year in my life, anywhere. It really affected my crops. Our hay was 9 percent protein. It would normally have been 18 or 20. Like I say, never in my life have I endured that much rain.

|

| Lengnick, Resilience Design Criteria for Agroecosystems |

Lengnick's distillation of

their advice is sage. Produce food as part of an ecosystem. Adapt by going back

to letting nature do what nature does best. Lengnick calls this "adaptive

management," but what she is speaking of is what the UN has been calling

"eco-agriculture, and it contains a suite of tools and practices that not

only provide greater food security but can, scaled quickly enough, undo the

worst of the Fossil Age's climate karma.

For Lengnick,

Functional diversity and response diversity describe the capacity of the agroecosystem to maintain healthy function of the four farming system processes (energy, water, mineral, community dynamics) and other ecosystem services. Functional diversity describes the number of different species or assemblages of species that participate in agroecosystem processes to produce ecosystem services. Response diversity describes the diversity of responses to changing conditions among the group of species or species assemblages that contribute to the same ecosystem function. Agroecosystems designed with high functional and response diversity have the capacity to produce ecosystem services over a wide range of environmental conditions.

Like Taleb, Lengnick identifies the

fragility of monocultural, industrial farming practices:

Appropriately connected agroecosystems will build relationships that enhance functional and response diversity. Many weak (i.e., not critical to function) connections are favored over a few strong (i.e., critical to function) connections. Agroecosystems that rely on a few strong connections for critical resources reduce their resilience to events that disrupt those connections; in contrast, many weak connections enhance response capacity.

In permaculture, we speak

of harmony and stress and some see those as opposites, but in a more tantric Buddhist interpretation they can be viewed as a symbiotic pair. Stress is the bending of a system

away from its natural pattern, making it fragile. Harmony is the restoration of

balance and connections, inherently antifragile. Natural succession is a cycle

of disturbance, experimentation, and equilibrium. There is no steady state,

there is only the constancy of change.

In permaculture, we speak

of harmony and stress and some see those as opposites, but in a more tantric Buddhist interpretation they can be viewed as a symbiotic pair. Stress is the bending of a system

away from its natural pattern, making it fragile. Harmony is the restoration of

balance and connections, inherently antifragile. Natural succession is a cycle

of disturbance, experimentation, and equilibrium. There is no steady state,

there is only the constancy of change.

In another month we leave

for Belize to teach the 11th annual Permaculture Design Course at

Maya Mountain Research Farm (seats still available here). Personally, it will be our 50th time instructing the

standard 72-hour Design Course. We often say, when we teach in such places, it

is not the people that are the instructors there, it is the land. In this case

it is land that has been refined, articulated, complexed and restored to if not

the Paleolithic model, then to a Neolithic transitional stage, where both

domestic and wild systems co-exist in a riot of cascading productivity.

If the Dwyer family had

taken this workshop, or read Lengnick's book, they would not have been caught

by surprise when their world of modern illusions suddenly dissolved. They would

probably never have gotten into that situation to begin with.

Comments