Search This Blog

We are in a crisis in the evolution of human society. It’s unique to both human and geologic history. It has never happened before and it can’t possibly happen again. Albert Bates, author of The Financial Collapse Survival Guide and Cookbook, brings you along on his personal journey.

Posts

Showing posts from July, 2017

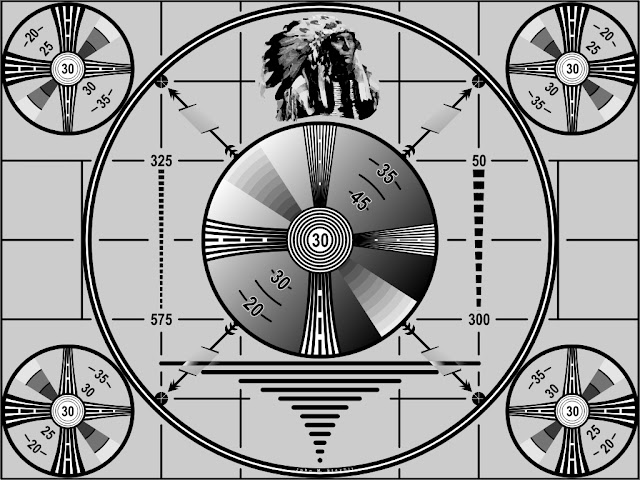

The Gospel of Chief Seattle: Written For Television

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps