Stephen Gaskin 1935-2014

"Eventually, Stephen will be reborn as a great oak, standing atop this knoll."

I heard a voice from heaven, saying unto me, Write, from henceforth blessed are the dead which die in the Lord: even so saith the Spirit: for they rest from their labours.

— Book of Common Prayer (1662)

As the trailing “mmmm” in my ahhhAAauuuuMMmmm moving slowly from the back of my throat forward to pinched lips dissolves into the chorus of birds and tree frogs I am left again in their raucus company, listening only to my breath and their voices. It is difficult to rise from meditation here in this beautiful spot, so I have begun noting my thoughts.

It is one week today since The Farm bid goodbye to Stephen Gaskin. I am seated in a forest glade at the highest point on the western Highland Rim of Middle Tennessee — 1120 feet above sea level. The sun has just risen and the forest is alive with birdsong and butterflies.

I remember this place from 40 years earlier, when it was open field and we were cultivating it for wheat, corn and soybeans. I drove the two-horse cultivator here. In 1973 I moved off Schoolhouse Ridge, where Stephen was my closest neighbor, up to Hickory Hill, a short hike from where I’m now sitting. The oaks there, top-graded in the 1940s, are now bigger than two people can stretch around and touch hands.

The birdsong here is very diverse. It’s an emergent forest and these trees are no more than 30 years. The self-selection, after The Farm quit commercial agriculture in the mid-1980s, favors flowering varieties like dogwood, wild cherry, persimmon, juniper and sumac, efficient resource scroungers in these ridge-top soils and part of the early succession stage that is reclaiming Shoemaker Field. Species common in early seres – growth rate maximized (R-selected) – usually focus on rapid extraction of resources and intense photosynthetic production even at the cost of efficient nutrient use. These colorful, scented and attractive pioneers will be replaced later by a more stable and balanced (K-selected) sere of locust, ash, sourwood, oak and hickory, much as we see on the other ridges. The bacterially dominant soils, useful for crops of vegetables and grains, will give way to fungal-dominant soils, and these speedy pioneers will be shaded out, die and decompose to provide space and supplies for succession.

All things garden. The rains will remove the traces of the clay that’s been turned when the grave was dug. Small saplings will send their roots down to consume any nutrient value in his body. Eventually, Stephen will be reborn as a great oak, standing atop this knoll, just near the summit of what the geodesic map calls Mt. Summer.

It was almost exactly 43 years ago this week that I stretched out on a giant boulder in Tuckerman’s Ravine in the White Mountains of New Hampshire and began turning the pages of Monday Night Class, a collection of transcripts of Stephen’s talks from 1967-70 published by a San Francisco co-op called Book People. What struck me as I read through the un-numbered, purple-inked pages was less about the philosophy or the Haight Ashbury scene than about a deeply penetrating sense of “these are my thoughts,” and “somebody has been having the same take on it as I do,” and “this guy is really good.”

A year later I was doing a through hike of the Appalachian Trail (a similar experience to that of Cheryl Strayed in Wild, soon to be a Reese Witherspoon film) and decided to stop at The Farm. I never left. I am here still. And the reason is something very close to what happened to me reading Monday Night Class. I was struck by how familiar it seemed. How right.

In a way that succession from R-sere to K-sere is an apt metaphor for The Farm and its relationship with Stephen. When we were probing for a way out of the militaristic mindset of the ‘50s, the exploitive brainfog of the adolescent ad age, with nihilistic consumerist growth madness auguring planetary ecocide, we found in Stephen amazing attributes of clarity, charisma (not a word he would've condoned), courage and willingness to step up to leadership and point us all towards a saner way to be, collectively. We pioneered, like weeds in barren soil, and birthed a new culture. We forged a steady-state, bioregional alternative to petrocollapse and the Venus Syndrome. We made it work, and we made it fun.

But that early stage of pioneering is no more sustainable than trying to live in a lifeboat. The juvenile growth phase is characterized by rapid morphological change (settling the land, building roads, water systems, schools, homes, businesses, etc., fighting off predators, and consuming your seed matter — our inheritances, our youth, our cheap fossil sunlight). For us, the limits to growth were slammed into by the early ‘80’s, and we found ourselves still inextricably tied to the larger economy (hospitals, energy, commerce, taxes), mired in debt (in no small measure from Stephen’s fearlessness — example: when on impulse he purchased a lemon semitractor-trailer without adequate inspection — and the Farm mechanics awarded him a Golden Bolt).

Historian Donald Pitzer has called what we experienced “developmental communalism.” Having a shared purse and not keeping score works great for R-sere societies, but once they have established they cannot keep growing without overrunning both resources and patience. At some scale they become less governable and corruption creeps in.

We had overgrown our rudimentary infrastructure and reached a crossroads — go back to something smaller and more pure by way of quaint example, or tune in, step up, and try to change the world by up-blending. As a rural commune we had made too many claims on underlying resources — a reckoning was required. Whether we wanted to be more mainstream or not, it had to happen. Given the mounting debts and legal threats, we could not keep the land otherwise. In 1984 we had our “Changeover” that revised the agreements. It was a new deck of cards.

When I first arrived in November, 1972, Stephen and his entourage were just leaving on a speaking and book/album launch tour. I spent most of that winter experiencing the trials and tribulations of an experimental community that did not have, nor seem to need, much leadership or organization. I would say one of my perennial disagreements with Stephen was over his strong antipathy to organization. It was evident to me, as a young paralegal eager to see everything made legally robust and bulletproof, that Stephen was determined to undermine anything that smacked of central authority or codifed rules. He did not want community by-laws or covenants, but eventually allowed me to gather up our “agreements,” so we could list those in the Supreme Court appeal about cultivation of marijuana for religious use (the appendix appears in a book published as The Grass Case). It took more than ten years before we eventually formed a “Constitutional Committee” to draw up by-laws for The Farm.

I would say one of my perennial disagreements with Stephen was over his strong antipathy to organization. It was evident to me, as a young paralegal eager to see everything made legally robust and bulletproof, that Stephen was determined to undermine anything that smacked of central authority or codifed rules. He did not want community by-laws or covenants, but eventually allowed me to gather up our “agreements,” so we could list those in the Supreme Court appeal about cultivation of marijuana for religious use (the appendix appears in a book published as The Grass Case). It took more than ten years before we eventually formed a “Constitutional Committee” to draw up by-laws for The Farm.

The Supreme Court brief has a delightful hippy flair, describing the agreements of the religious society and showing early pictures of the community. Stephen, as head of his own legal team, insisted that no "legal technicalities" be employed in the defense strategy, even though he might well have been acquitted on the unlawful warrant and bad search. Instead, as the brief illustrates, he wanted to tell the "system" simply what the truth of the matter is — that government has no business interfering with how people come to God. He gave a year of his life — behind bars, in prison — for the privilege of raising the point in that way.

Like any man, he made mistakes, sometimes catastrophic, with consequences that affected the many who relied on his judgment. He excelled not just in strong leadership but in boneheaded stubbornness, which might work well in situations requiring courage under stress, but not when what is needed is to anneal energy in a fractious group. Stephen was just a man. But what an extraordinary man he was. When he died the remembrances came cascading in.

In Stockholm, Right Livelihood Award Founder Jakob von Uexkull reflected,

Mark Madrid, a long-time resident of The Farm and part of the Muscogee Nation in Oklahoma, said:

Martin Holsinger, now a radio show host in Nashville, said:

Lois Latman recalled:

Elizabeth Barger, who publishes The Farm Freedom Press, wrote:

Spider Robinson, science fiction author, wrote:

Those who knew the man well knew his heart was as big as the moon. You don’t have to take my word for it. Here is a short video clip from 1974. (If it doesn't display properly, go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ht9z1ingSZc)

I think watching this video in the community center at Sunday services, just following the meditation, was the peak for me of many powerful experiences of the past weekend. Being someone who does public speaking now I am always watching moves and picking up on technique. That short talk defies any such dissection. It was from the heart from someone who was absolutely at the top of his game. The talk pulled together the "three-legged stool" of social justice, ecology and steady-state economics. It addressed ecological limits as though it were 40 years later. Remarkable especially when you put that scene in the context of Stephen in 1974, when he was serving time in the State Penitentiary. He walked out of the pen in cuffs, changed to that white turtleneck and embroidered jean jacket, was driven down to The Farm, spoke and then turned around and went right back the other way, into cuffs and stripes again, day-furlough ended. There was not the slightest trace of that context at all in the delivery, just the larger message, with sure, steady voice, straight from the heart. Awesome.

If I have any gripes about the uplinked video I wish that it could have started 3 or 4 minutes earlier. Stephen says nothing. He rises from the meditation. He picks up the microphone. He looks up. He catches eyes here and there. He looks back down, seeming to think about what he might say. He looks up again, looks around. Breathes. Smiles. Looks thoughtful. Looks back down. This goes on a long time. I understand why it was deleted but again, I am a public speaker now. I would find it very difficult to share so much “dead air time” with an audience. He had absolute confidence that people would forgive him while he gathered his thoughts to speak, and so said nothing. And then he was ready, and the tape begins.

After morning service in the community center, his partner Ina May hosted a reception at Stephen’s home, where he had passed quietly after being bedridden and in progressive decline for many months. He was still in good humor and wisecracking to the end.

At the morning service, his oldest daughter, Dana, spoke first, after the video.

Stephen confounded many in his family* and the community by asking his son to carry his body deep into the forest and bury it in an unmarked grave. This place.

This is not a biographical sketch. Others have done that more will still do that. I cannot attempt that here. When I'm first got to know Stephen I was 25 and he was someone I looked up to, a wise elder who was not afraid to admit his mistakes or foibles. Now I am 67, and I know he was right most of the time. As someone who walked in his footprints to learn what he knew and was inspired to exceed even what I thought in my wildest imagination might be possible, I have nothing but gratitude.

All I can say is, goodbye friend, it has been really, really great.

*In the comments that follow Dana Gaskin Wetig writes, "the rest of the family has been offered no proof that Stephen asked to be buried in an unmarked grave."

|

| Stephen Gaskin, at The Farm in 2013 |

— Book of Common Prayer (1662)

As the trailing “mmmm” in my ahhhAAauuuuMMmmm moving slowly from the back of my throat forward to pinched lips dissolves into the chorus of birds and tree frogs I am left again in their raucus company, listening only to my breath and their voices. It is difficult to rise from meditation here in this beautiful spot, so I have begun noting my thoughts.

It is one week today since The Farm bid goodbye to Stephen Gaskin. I am seated in a forest glade at the highest point on the western Highland Rim of Middle Tennessee — 1120 feet above sea level. The sun has just risen and the forest is alive with birdsong and butterflies.

I remember this place from 40 years earlier, when it was open field and we were cultivating it for wheat, corn and soybeans. I drove the two-horse cultivator here. In 1973 I moved off Schoolhouse Ridge, where Stephen was my closest neighbor, up to Hickory Hill, a short hike from where I’m now sitting. The oaks there, top-graded in the 1940s, are now bigger than two people can stretch around and touch hands.

The birdsong here is very diverse. It’s an emergent forest and these trees are no more than 30 years. The self-selection, after The Farm quit commercial agriculture in the mid-1980s, favors flowering varieties like dogwood, wild cherry, persimmon, juniper and sumac, efficient resource scroungers in these ridge-top soils and part of the early succession stage that is reclaiming Shoemaker Field. Species common in early seres – growth rate maximized (R-selected) – usually focus on rapid extraction of resources and intense photosynthetic production even at the cost of efficient nutrient use. These colorful, scented and attractive pioneers will be replaced later by a more stable and balanced (K-selected) sere of locust, ash, sourwood, oak and hickory, much as we see on the other ridges. The bacterially dominant soils, useful for crops of vegetables and grains, will give way to fungal-dominant soils, and these speedy pioneers will be shaded out, die and decompose to provide space and supplies for succession.

All things garden. The rains will remove the traces of the clay that’s been turned when the grave was dug. Small saplings will send their roots down to consume any nutrient value in his body. Eventually, Stephen will be reborn as a great oak, standing atop this knoll, just near the summit of what the geodesic map calls Mt. Summer.

|

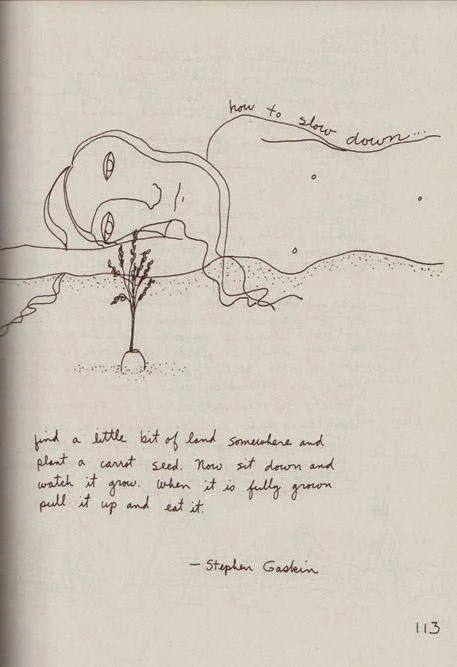

| From Living on Earth by Alicia Bay Laurel |

It was almost exactly 43 years ago this week that I stretched out on a giant boulder in Tuckerman’s Ravine in the White Mountains of New Hampshire and began turning the pages of Monday Night Class, a collection of transcripts of Stephen’s talks from 1967-70 published by a San Francisco co-op called Book People. What struck me as I read through the un-numbered, purple-inked pages was less about the philosophy or the Haight Ashbury scene than about a deeply penetrating sense of “these are my thoughts,” and “somebody has been having the same take on it as I do,” and “this guy is really good.”

A year later I was doing a through hike of the Appalachian Trail (a similar experience to that of Cheryl Strayed in Wild, soon to be a Reese Witherspoon film) and decided to stop at The Farm. I never left. I am here still. And the reason is something very close to what happened to me reading Monday Night Class. I was struck by how familiar it seemed. How right.

In a way that succession from R-sere to K-sere is an apt metaphor for The Farm and its relationship with Stephen. When we were probing for a way out of the militaristic mindset of the ‘50s, the exploitive brainfog of the adolescent ad age, with nihilistic consumerist growth madness auguring planetary ecocide, we found in Stephen amazing attributes of clarity, charisma (not a word he would've condoned), courage and willingness to step up to leadership and point us all towards a saner way to be, collectively. We pioneered, like weeds in barren soil, and birthed a new culture. We forged a steady-state, bioregional alternative to petrocollapse and the Venus Syndrome. We made it work, and we made it fun.

But that early stage of pioneering is no more sustainable than trying to live in a lifeboat. The juvenile growth phase is characterized by rapid morphological change (settling the land, building roads, water systems, schools, homes, businesses, etc., fighting off predators, and consuming your seed matter — our inheritances, our youth, our cheap fossil sunlight). For us, the limits to growth were slammed into by the early ‘80’s, and we found ourselves still inextricably tied to the larger economy (hospitals, energy, commerce, taxes), mired in debt (in no small measure from Stephen’s fearlessness — example: when on impulse he purchased a lemon semitractor-trailer without adequate inspection — and the Farm mechanics awarded him a Golden Bolt).

Historian Donald Pitzer has called what we experienced “developmental communalism.” Having a shared purse and not keeping score works great for R-sere societies, but once they have established they cannot keep growing without overrunning both resources and patience. At some scale they become less governable and corruption creeps in.

We had overgrown our rudimentary infrastructure and reached a crossroads — go back to something smaller and more pure by way of quaint example, or tune in, step up, and try to change the world by up-blending. As a rural commune we had made too many claims on underlying resources — a reckoning was required. Whether we wanted to be more mainstream or not, it had to happen. Given the mounting debts and legal threats, we could not keep the land otherwise. In 1984 we had our “Changeover” that revised the agreements. It was a new deck of cards.

When I first arrived in November, 1972, Stephen and his entourage were just leaving on a speaking and book/album launch tour. I spent most of that winter experiencing the trials and tribulations of an experimental community that did not have, nor seem to need, much leadership or organization.

I would say one of my perennial disagreements with Stephen was over his strong antipathy to organization. It was evident to me, as a young paralegal eager to see everything made legally robust and bulletproof, that Stephen was determined to undermine anything that smacked of central authority or codifed rules. He did not want community by-laws or covenants, but eventually allowed me to gather up our “agreements,” so we could list those in the Supreme Court appeal about cultivation of marijuana for religious use (the appendix appears in a book published as The Grass Case). It took more than ten years before we eventually formed a “Constitutional Committee” to draw up by-laws for The Farm.

I would say one of my perennial disagreements with Stephen was over his strong antipathy to organization. It was evident to me, as a young paralegal eager to see everything made legally robust and bulletproof, that Stephen was determined to undermine anything that smacked of central authority or codifed rules. He did not want community by-laws or covenants, but eventually allowed me to gather up our “agreements,” so we could list those in the Supreme Court appeal about cultivation of marijuana for religious use (the appendix appears in a book published as The Grass Case). It took more than ten years before we eventually formed a “Constitutional Committee” to draw up by-laws for The Farm.The Supreme Court brief has a delightful hippy flair, describing the agreements of the religious society and showing early pictures of the community. Stephen, as head of his own legal team, insisted that no "legal technicalities" be employed in the defense strategy, even though he might well have been acquitted on the unlawful warrant and bad search. Instead, as the brief illustrates, he wanted to tell the "system" simply what the truth of the matter is — that government has no business interfering with how people come to God. He gave a year of his life — behind bars, in prison — for the privilege of raising the point in that way.

Like any man, he made mistakes, sometimes catastrophic, with consequences that affected the many who relied on his judgment. He excelled not just in strong leadership but in boneheaded stubbornness, which might work well in situations requiring courage under stress, but not when what is needed is to anneal energy in a fractious group. Stephen was just a man. But what an extraordinary man he was. When he died the remembrances came cascading in.

In Stockholm, Right Livelihood Award Founder Jakob von Uexkull reflected,

"Stephen Gaskin received the first Right Livelihood Award in 1980 for the work of PLENTY International. The name says it all: Stephen believed that there is plenty for all if we share. PLENTY aid projects have been very effective because they were run by people who understood the differences between misery, poverty and voluntarily living simply from personal experience. Stephen represented a different, hopeful vision of America. He has inspired several generations by showing how materially simple and spiritually rich lives are possible today and can guide us to a sustainable future."Manitonquat (Medicine Story) said Stephen, whose Right Livelihood Award was in part for his work with indigenous peoples, was a "pioneer thinker and inspiration in our work to change the world by way of more human, more compassionate communities consciously created and fashioned to activate our human need to be helpful and make life more wonderful for all people."

Mark Madrid, a long-time resident of The Farm and part of the Muscogee Nation in Oklahoma, said:

“In our Mvskoke culture, there is the Micco (the one) the Empv'nvke (the Speaker) and the tvs'tvnvke (Security/ Enforcers). He was the Speaker, voicing the peoples mind.”Dan Sallberg wrote:

“It was January, 1971 and I was 21 years old. My daughter was a month old. I was unemployed. We were living on welfare and food stamps. I volunteered to be a receptionist at the Pasadena Free Clinic, just for something to do. I found an interview with Stephen Gaskin in a copy of Mademoiselle Magazine. I’m pretty sure it had something to do with the school-bus caravan lecture tour. I know I read the whole interview. I forget most of it. But there was one part that changed my life forever. Mr. Gaskin advised anti-establishment hippies to get off welfare and stop mooching off the establishment, and to get involved in positive, alternative activities that would create a better world. A month later I was the graveyard dishwasher and janitor at a 24-hour a day vegetarian restaurant called H.E.L.P. (Health through Education creates internal Love which manifests Peace within) Restaurant on the corner of 3rd and Fairfax in Los Angeles. Three months later we got off welfare. I stayed in the natural foods business for another 15 years until it outgrew me and I eventually became a math and science teacher for students with special needs. Thank you, Stephen”Apple Co-founder Steve Wozniak said:

"In every walk of life we take care of each other and owe all that we achieve to friends and family. How we treat other humans is much more important than creating products and wealth. Our principles in life should always be much more important than that. As much as we can teach others, our actions and examples pass on the goodness in our heads to others. Thank you for inspiration at a critical time in my life when I was deciding what sort of person I wanted to be."

Martin Holsinger, now a radio show host in Nashville, said:

“The Farm as ‘Stephen’s family monastery’ for all its imperfections, was the best home I ever had, an experience I have been trying in vain to recreate ever since it came unglued in the early 80’s. Thank you, Stephen, for helping me and so many others live in a better world, even if only for a few years, and thank you for pointing me to Buddhism, which in so many ways has carried on the changes in me that you helped initiate. Thank you for my first marriage, for my children, my grandchildren, and my soon-to-be great grandchild. My children, and their children, are here because of you. Thank you for encouraging me to maintain a friendly but uppity attitude towards authority/mainstream culture. I am who I am because of you, and I have always been grateful to you for that.

Lois Latman recalled:

“One thing I remember about Stephen is him giving away two houses that the construction crew built for him and his family in the early 70's. The first one that got built on second road, he wouldn't move into, but gave it to a group of single mothers. The second one, Kissing Tree, he gave to my Uncle Bill and his caregivers. Stephen remained in an army tent with his family, which he eventually replaced by a house on the same site. He did not want to live above the means of the rest of the community.”

|

| Altar to Stephen that appeared in San Francisco on Dia de los Muertos, 2014 |

“Many of us remember that he said he was not “the leader” but a teacher who might teach us something that would be useful to us. I think he did that a while ago. The Farm has been moving forward for some time since his retirement. The teachings are good and the spirit is strong. The place we call The Farm remains as a growing marker for the experiment to continue.”

Spider Robinson, science fiction author, wrote:

“Stephen spent most of every day scheming ways to make this world a better, kinder place—with an unusually high success rate. I consider him one of the wisest, most compassionate men I’ve ever met, and the most generous. Without him Jeanne and I would never have been chosen Celebrity Judges for the 2001 Amsterdam Cannabis Cup, one of the happiest gigs we ever had, and the first time we ever seriously impressed our daughter with her parents’ fame. Our own Nova Scotia commune, the Moonrise Hill Gang, basically existed because a bunch of us had heard about what Stephen was doing, and wanted to emulate it ourselves. It didn’t work because we had no Stephen.

“But I suspect we may have to wait awhile before someone emerges to become the next Stephen.

“He was one of the best human beings I ever met, flawed like all humans, but fundamentally good to his shoes, and unless we get really lucky, we won’t see his like again soon.”The “newsers,” as Stephen would call them, as usual, got the obits wrong. Some, like The Tennessean and the Washington Post landed not far from the mark. The Post quoted Stephen saying of the Changeover, “I’m a beatnik. I honestly liked it better when it was a circus… But I also like being solvent.” Others, like CNN and The New York Times were wildly disrespectful, hammering on the 1971 drug bust (ironically, since Tennessee recently became the 4th US State to legalize marijuana cultivation), the number of Green Party votes he got in the Presidential primary, or other distractions. In all, more than 100 newspapers around the world ran stories.

Those who knew the man well knew his heart was as big as the moon. You don’t have to take my word for it. Here is a short video clip from 1974. (If it doesn't display properly, go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ht9z1ingSZc)

I think watching this video in the community center at Sunday services, just following the meditation, was the peak for me of many powerful experiences of the past weekend. Being someone who does public speaking now I am always watching moves and picking up on technique. That short talk defies any such dissection. It was from the heart from someone who was absolutely at the top of his game. The talk pulled together the "three-legged stool" of social justice, ecology and steady-state economics. It addressed ecological limits as though it were 40 years later. Remarkable especially when you put that scene in the context of Stephen in 1974, when he was serving time in the State Penitentiary. He walked out of the pen in cuffs, changed to that white turtleneck and embroidered jean jacket, was driven down to The Farm, spoke and then turned around and went right back the other way, into cuffs and stripes again, day-furlough ended. There was not the slightest trace of that context at all in the delivery, just the larger message, with sure, steady voice, straight from the heart. Awesome.

If I have any gripes about the uplinked video I wish that it could have started 3 or 4 minutes earlier. Stephen says nothing. He rises from the meditation. He picks up the microphone. He looks up. He catches eyes here and there. He looks back down, seeming to think about what he might say. He looks up again, looks around. Breathes. Smiles. Looks thoughtful. Looks back down. This goes on a long time. I understand why it was deleted but again, I am a public speaker now. I would find it very difficult to share so much “dead air time” with an audience. He had absolute confidence that people would forgive him while he gathered his thoughts to speak, and so said nothing. And then he was ready, and the tape begins.

After morning service in the community center, his partner Ina May hosted a reception at Stephen’s home, where he had passed quietly after being bedridden and in progressive decline for many months. He was still in good humor and wisecracking to the end.

At the morning service, his oldest daughter, Dana, spoke first, after the video.

“To say my father was charismatic is a gross understatement. His compelling charm and strength of conviction is how we all got here, how this place came to be. As a kid I thought I had to stand in line to be with him, take my turn like everyone else. I was in my teens before he told me different.

Stephen and Dana, 1962

My dad shared his love of books and reading with me early. When I got tired of kids books, he handed me Doc Strange comic books, Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse, the Tolkein trilogy, Theodore Sturgeon’s More Than Human, Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, and Parmahansa Yogananda’s, Autobiography of a Yogi, which read like science fiction. I’m so grateful to him for introducing me to the joys of getting lost in stories and for sharing his favorites with me.

My dad loved heroes. In the face of difficulty, he’d proclaim, "Here I've come to save the day!" from the Sergeant Preston of the Yukon radio show. And he always tried to do that, save the day - "Out to Save the World" was his stated destination. I’m grateful to have grown up around people who believed that making meaningful change is possible. Plenty International, the Farmer Veteran Coalition, and many other farm-grown organizations continue that important work.

Most of you know that my dad was a Marine and served in Korea. When he came home in 1954, he had the shakes, shellshock, what we know now as Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. My mom says he tried drinking it away – luckily his stomach wouldn’t take that. Marijuana helped him with stress relief for decades. That and his favorite ‘trash:’ Candy Corn, Circus Peanuts, Red Hots, Necco Wafers, and Heath Bars, saw him through.

Stephen and Dana, 1968

My dad loved cars as much as he loved road trips. I’ve been through every state but Alaska on road trips with my dad, and down to Guatemala twice. He loved adventure. I am comforted by the thought that this new adventure is just another road trip for him: The ultimate road trip. Like Swami Beyondananda says, "The bad news: There is no key to the universe. The good news: It was never locked."

Stephen confounded many in his family* and the community by asking his son to carry his body deep into the forest and bury it in an unmarked grave. This place.

This is not a biographical sketch. Others have done that more will still do that. I cannot attempt that here. When I'm first got to know Stephen I was 25 and he was someone I looked up to, a wise elder who was not afraid to admit his mistakes or foibles. Now I am 67, and I know he was right most of the time. As someone who walked in his footprints to learn what he knew and was inspired to exceed even what I thought in my wildest imagination might be possible, I have nothing but gratitude.

All I can say is, goodbye friend, it has been really, really great.

*In the comments that follow Dana Gaskin Wetig writes, "the rest of the family has been offered no proof that Stephen asked to be buried in an unmarked grave."

Comments

Thank you for this very fitting tribute. My condolences to you, to the Gaskin family and to the Farm Community.

Best, Dana Gaskin Wenig