Operation Protective Edge: One Hundred Thirty Nine Square Miles of Sand, Part I

""Mr. Balfour, supposing I was to offer you Paris instead of London, would you take it?" He sat up, looked at me, and answered: "But Dr. Weizmann, we have London." "That is true," I said, "but we had Jerusalem when London was a marsh.""

Events in Gaza fill us with deep sadness. We have friends in both Israel and Palestine who are swept into this conflict without wanting it. To them, as to us, it seems a doorless, windowless room. There is no escape, no illumination, no good reason for being there and no way to leave.

To get out of this room, we have to understand how it was built and why it is here. We have to cut a window to let some light in, and then build a door from the inside out.

When we first visited Israel, in the summer of 1991, Gaza City was much like the other ocean-front cities of the Mediterranean — stone buildings and winding streets, a long seawall, lovely beaches. Even though it had just been through the 1987 Intifada, it retained the charm of Jappa and Haifa. Fishermen gathered before dawn and shoved out with the tide, returning at midday with their catches. Shopkeepers sold antiques and fine needlework from stores below their homes. Apart from the tanks, barbed wire and ubiquitous IDF soldiers, Gaza Beach was a tranquil paradise.

In 1991 a young guard assigned to the Gaza Beach internment camp wrote for The New York Review of Books, “One day, if there is a state called Palestine, its government will no doubt lease this piece of ground to some international entrepreneur who would set up a Club Med Gaza Beach.”

In 1948, Gaza City, and the “Gaza Strip” became the refuge of people fleeing war after their homes, olive groves, barns and villages were destroyed, their cattle and goats machine-gunned, and their water, sewage and electricity cut off. Then, in 1967, tanks arrived at the beach, and there was nowhere left to flee. Some lucky enough to escape went to Egypt, and when Egyptians were no longer willing to feed, house or employ the growing tide of refugees, they closed the border. Even then, Gazans dug long tunnels, or tried to cross by boat.

In 1991 that young Israeli prison guard wrote:

Back in 1894, a Jewish lieutenant in the French Army, Alfred Dreyfus, was tried for treason. He was wrongfully accused, which soon became apparent, but with the anti-Semitic right-wing having taken power in Paris, and the French public inflamed, the Army feared public accusations of Jewish favoritism if Dreyfus was tried and acquitted. Dreyfus was scapegoated — summarily convicted and sentenced to prison.

In Paris to cover the trial for the Vienna News Free Press, Theodor Herzl was shocked at the open anti-Semitism he witnessed. If anti-Semitism could flourish in the most tolerant and progressive country in Europe, Herzl reasoned, Jews would only be safe in their own state. If they had to design a nation, what might it look like? Herzl imagined a socialist paradise — no poor, no ruling class, food and shelter for everyone. He wrote a bestselling book, The Jewish State, promoting his ideas, which eventually went viral as Zionism. Herzl’s reaction to the right wing excesses in France gave birth, half a century later, to the utopian dream of Israel.

In the late 19th century, facing growing persecution in Eastern Europe and pogroms in Russia, Jews began flowing to Palestine for refuge. Near Jaffa an agricultural school, the Mikveh Israel, was founded. Russian Jews established the Bilu and Hovevei Zion ("Love of Zion") movements to assist settlers, who created self-reliant experimental agricultural communes that sought to get beyond the utopian “Holy Cities” of the Ashkenazi-Jews and not rely on donations from Europe.

The hardy arrivals, mostly from Russia — the First Aliyah, some 35,000 between 1882 and 1903 — revived the Hebrew language, developed drip irrigation, and greened the desert. They blended into and got along with the complex mix of Druze, Bedouin and Christian and Muslim Arabs. By 1890, Jews were a majority in Jerusalem. In 1909 residents of Jaffa established the first entirely Hebrew-speaking city, Ahuzat Bayit (later renamed Tel Aviv).

We have previously written of the seminal role of Lady Evelyn Balfour in the creation of organic gardening and the founding of the first Soil Association. We have not previously mentioned her very interesting uncle, Arthur James, First Earl of Balfour, British Prime Minister from 1902 to 1905.

Lord Balfour is also known for his noble mien — the Balfourian manner. A journalist of his time described it this way:

"The truth about Arthur Balfour," said George Wyndham, "is this: he knows there's been one ice-age, and he thinks there's going to be another."

We are fond of Balfour, not just because he was apparently a protocollapsenik, but also because in his later years he argued that Darwin’s premise of selection for reproductive fitness cast doubt on scientific naturalism — the belief that there are no supernatural entities or processes — because human cognitive facilities that would accurately perceive truth would be at a disadvantage against competing humans genetically selecting for evolutionarily useful illusions.

While Balfour tilted towards the supernatural as a boon to humanity, his thesis goes a long way to explain the great smoldering track of the Advertising Age through our species’ inate common sense and our presently diminished capacity to survive the coming Anthropocene extinction.

Long evolved discriminatory abilities that assisted distant future pattern recognition and might have helped our survival are being bred out by twerking, gangsta rap, and The Shopping Network, leaving only the comfort of our illusions.

Despite his belief in the futility of action, Balfour, in his manner, could not resist the urge to meddle in world affairs. Like a child with an anthill and a magnifying glass on a sunny day he found special interest in Zionists. Meeting Chaim Weizmann, a wealthy British Zionist, in 1906, Balfour asked Weizmann what he thought of the idea of a Jewish homeland in Uganda, a British Protectorate.

According to Weizmann's memoir, the conversation went as follows:

This prompted a letter from Alfred, First Earl Balfour to Walter, Second Baron Rothschild, a prominent funder of the first kibbutzim. Balfour wrote:

The overarching aim of Balfour was to gain support of both the Americans and the Bolsheviks for British aims in the Middle East. The Transjordan coast was strategically important as a check to Egypt at the Suez Canal, and there were already thoughts of a Mosul-Haifa pipeline to transport oil from Kirkuk. Two of President Woodrow Wilson's closest advisors, Louis Brandeis and Felix Frankfurter, were avid Zionists. Several of the most prominent Russian revolutionaries, including Leon Trotsky, were also. The Foreign Secretary wanted to keep both the USA and Russia in the war and used the potential separation of a Zionist state from Transjordan as bait.

In November 1918 the large group of Palestinian Arab dignitaries and representatives of political associations forwarded a petition to the British authorities in which they decried the hubris of the declaration. The document stated:

The British Mandate of Palestine was confirmed by the League of Nations in 1922 and came into effect in 1923. The boundaries of Palestine initially included modern Jordan, which was removed from the territory by Churchill a few years later. The United States, whose Senate refused to join Wilson’s League of Nations, signed a separate endorsement treaty.

Between 1919 and 1923, 40,000 Jews arrived in Palestine, mainly escaping the post-revolutionary chaos of Russia and Ukraine (the Third Aliyah) where over 100,000 Jews had been massacred. These immigrants were called halutzim (pioneers) because they were experienced in agriculture and quick to establish self-sustaining frontier towns. The Jezreel Valley and the Hefer Plain marshes were purchased through foreign donations, drained and converted to agricultural settlements. A socialist underground militia, the Haganah ("defense") sprang up to defend the outlying settlements.

Despite Palestinian Arab rioting in 1920 and 1922, 82,000 more Jewish refugees had arrived by 1929 (the Fourth Aliyah), fleeing pogroms in Poland and Hungary and rebuffed by the anti-Semitic United States Immigration Act of 1924.

The British governors of Palestine rejected the principle of majority rule or any other measure that would give the Arab population, who formed the majority, control over Jewish territory. The United States, whose strategic objective (oft quoted by comedian Robert Newman in A History of Oil) was “to bring democracy to the Middle East,” supported this policy, and still supports it today.

Following World War II, oil interests in the Middle East tilted western allies towards the Arabs. In an effort to win independence, underground Jewish militias waged a guerrilla war against the British. From 1929 to 1945, 110,000 Jews entered Palestine illegally (Bet Aliyah). Between 1945 and 1948, 250,000 Holocaust surviving Jews left Poland, Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia for refuge in Palestine. Most of these refugees were intercepted by the British and interred in squalid camps in Cyprus. Finally, under pressure from their Arab oil partners, the British had enough, and referred the whole matter to the United Nations.

Following World War II, oil interests in the Middle East tilted western allies towards the Arabs. In an effort to win independence, underground Jewish militias waged a guerrilla war against the British. From 1929 to 1945, 110,000 Jews entered Palestine illegally (Bet Aliyah). Between 1945 and 1948, 250,000 Holocaust surviving Jews left Poland, Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia for refuge in Palestine. Most of these refugees were intercepted by the British and interred in squalid camps in Cyprus. Finally, under pressure from their Arab oil partners, the British had enough, and referred the whole matter to the United Nations.

The UN, looking at the status quo on the ground, drew this map, which is probably the worst partition ever conceived.

On November 29, 1947, in Resolution 181 (II), the UN General Assembly recommended a plan to replace the British Mandate with separate "Independent Arab and Jewish States" and a "Special International Regime for the City of Jerusalem administered by the United Nations."

Neither Britain nor the UN took any action to implement the resolution and Britain continued detaining Jews attempting to enter Palestine. The British withdrew forces in May 1948, but continued to hold Jews of "fighting age" and their families on Cyprus until March 1949, anticipating what was about to happen.

What was about to happen was the delivery of the promised utopia to the Jews and a catastrophe for the Palestinians.

To be continued

|

| Operation Protective Edge, 2014 |

To get out of this room, we have to understand how it was built and why it is here. We have to cut a window to let some light in, and then build a door from the inside out.

When we first visited Israel, in the summer of 1991, Gaza City was much like the other ocean-front cities of the Mediterranean — stone buildings and winding streets, a long seawall, lovely beaches. Even though it had just been through the 1987 Intifada, it retained the charm of Jappa and Haifa. Fishermen gathered before dawn and shoved out with the tide, returning at midday with their catches. Shopkeepers sold antiques and fine needlework from stores below their homes. Apart from the tanks, barbed wire and ubiquitous IDF soldiers, Gaza Beach was a tranquil paradise.

In 1991 a young guard assigned to the Gaza Beach internment camp wrote for The New York Review of Books, “One day, if there is a state called Palestine, its government will no doubt lease this piece of ground to some international entrepreneur who would set up a Club Med Gaza Beach.”

In 1948, Gaza City, and the “Gaza Strip” became the refuge of people fleeing war after their homes, olive groves, barns and villages were destroyed, their cattle and goats machine-gunned, and their water, sewage and electricity cut off. Then, in 1967, tanks arrived at the beach, and there was nowhere left to flee. Some lucky enough to escape went to Egypt, and when Egyptians were no longer willing to feed, house or employ the growing tide of refugees, they closed the border. Even then, Gazans dug long tunnels, or tried to cross by boat.

In 1991 that young Israeli prison guard wrote:

In Gaza it’s all straightforward and clear. There’s no place to hide. And I think: What if someone were to sneak a hidden camera in here? If only Robert Capa were alive. If only Claude Lanzmann were to make a film here. He would see a bored soldier who sits and solves crossword puzzles chewing on his pencil, under the apparently innocent sign: “Compound Number 1,” while another soldier, one or our charming Sabra types, a youth from a Tel Aviv suburb, walks around with a wreath of handcuffs over his shoulder.

Then he might turn his camera on the forty-one prisoners whom we shove into the narrow filthy detention cell in the government building in Gaza. They are awaiting trial. Because they have no room to move, because they are squeezed one against the other from morning until noon like cattle, they press ever more tightly up against the bars on the door to the detention cell so as to gulp in a little air. And because the door is too narrow for them all, some collapse, and some crawl under the legs of others. And the seven or eight who are caught on the bars appear, without intending or knowing it, as a kind of living statue, a mute poster of protest against imprisonment and oppression.In that summer of 1991, near Dagania, the first kibbutz (1909), we laid wildflowers on the tomb of Theodor Herzl, the conceiver of Israel, and placed a small stone on the grave of Rachel, the country’s first Poet Laureate. We walked with elderly IDF veterans to see the foxholes they had dug at the Jordan River in May of 1948. We immersed ourselves in the history of this place, visiting the chapel on the Mount of Olives and the archaeological dig at Capernaum. We stood upon the rock from which the young Jesus of Nazareth was said to hail the fishermen in the Sea of Galilee, telling them to cast their net on the other side of the boat.

Back in 1894, a Jewish lieutenant in the French Army, Alfred Dreyfus, was tried for treason. He was wrongfully accused, which soon became apparent, but with the anti-Semitic right-wing having taken power in Paris, and the French public inflamed, the Army feared public accusations of Jewish favoritism if Dreyfus was tried and acquitted. Dreyfus was scapegoated — summarily convicted and sentenced to prison.

In Paris to cover the trial for the Vienna News Free Press, Theodor Herzl was shocked at the open anti-Semitism he witnessed. If anti-Semitism could flourish in the most tolerant and progressive country in Europe, Herzl reasoned, Jews would only be safe in their own state. If they had to design a nation, what might it look like? Herzl imagined a socialist paradise — no poor, no ruling class, food and shelter for everyone. He wrote a bestselling book, The Jewish State, promoting his ideas, which eventually went viral as Zionism. Herzl’s reaction to the right wing excesses in France gave birth, half a century later, to the utopian dream of Israel.

In the late 19th century, facing growing persecution in Eastern Europe and pogroms in Russia, Jews began flowing to Palestine for refuge. Near Jaffa an agricultural school, the Mikveh Israel, was founded. Russian Jews established the Bilu and Hovevei Zion ("Love of Zion") movements to assist settlers, who created self-reliant experimental agricultural communes that sought to get beyond the utopian “Holy Cities” of the Ashkenazi-Jews and not rely on donations from Europe.

The hardy arrivals, mostly from Russia — the First Aliyah, some 35,000 between 1882 and 1903 — revived the Hebrew language, developed drip irrigation, and greened the desert. They blended into and got along with the complex mix of Druze, Bedouin and Christian and Muslim Arabs. By 1890, Jews were a majority in Jerusalem. In 1909 residents of Jaffa established the first entirely Hebrew-speaking city, Ahuzat Bayit (later renamed Tel Aviv).

We have previously written of the seminal role of Lady Evelyn Balfour in the creation of organic gardening and the founding of the first Soil Association. We have not previously mentioned her very interesting uncle, Arthur James, First Earl of Balfour, British Prime Minister from 1902 to 1905.

Lord Balfour is also known for his noble mien — the Balfourian manner. A journalist of his time described it this way:

“This Balfourian manner, as I understand it, has its roots in an attitude of mind—an attitude of convinced superiority which insists in the first place on complete detachment from the enthusiasms of the human race, and in the second place on keeping the vulgar world at arm's length. It is an attitude of mind … of one who desires rather to observe the world than to shoulder any of its burdens.”

"The truth about Arthur Balfour," said George Wyndham, "is this: he knows there's been one ice-age, and he thinks there's going to be another."

We are fond of Balfour, not just because he was apparently a protocollapsenik, but also because in his later years he argued that Darwin’s premise of selection for reproductive fitness cast doubt on scientific naturalism — the belief that there are no supernatural entities or processes — because human cognitive facilities that would accurately perceive truth would be at a disadvantage against competing humans genetically selecting for evolutionarily useful illusions.

While Balfour tilted towards the supernatural as a boon to humanity, his thesis goes a long way to explain the great smoldering track of the Advertising Age through our species’ inate common sense and our presently diminished capacity to survive the coming Anthropocene extinction.

Long evolved discriminatory abilities that assisted distant future pattern recognition and might have helped our survival are being bred out by twerking, gangsta rap, and The Shopping Network, leaving only the comfort of our illusions.

Despite his belief in the futility of action, Balfour, in his manner, could not resist the urge to meddle in world affairs. Like a child with an anthill and a magnifying glass on a sunny day he found special interest in Zionists. Meeting Chaim Weizmann, a wealthy British Zionist, in 1906, Balfour asked Weizmann what he thought of the idea of a Jewish homeland in Uganda, a British Protectorate.

According to Weizmann's memoir, the conversation went as follows:

"Mr. Balfour, supposing I was to offer you Paris instead of London, would you take it?" He sat up, looked at me, and answered: "But Dr. Weizmann, we have London." "That is true," I said, "but we had Jerusalem when London was a marsh." He ... said two things which I remember vividly. The first was: "Are there many Jews who think like you?" I answered: "I believe I speak the mind of millions of Jews whom you will never see and who cannot speak for themselves." ... To this he said: "If that is so you will one day be a force." (Weizmann, Trial and Error, p.111, as quoted in W. Lacquer, The History of Zionism, 2003, p.188).Flash forward 8 years to November, 1914 and the retired Prime Minister is now British Foreign Secretary as his country is at war with the Ottoman Empire over oil and the Berlin-to-Baghdad railroad. A fellow cabinet official, Herbert Samuel, circulates a memorandum entitled “The Future of Palestine” to his colleagues. The memorandum begins with "I am assured that the solution of the problem of Palestine which would be much the most welcome to the leaders and supporters of the Zionist movement throughout the world would be the annexation of the country to the British Empire.”

This prompted a letter from Alfred, First Earl Balfour to Walter, Second Baron Rothschild, a prominent funder of the first kibbutzim. Balfour wrote:

“His Majesty's government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

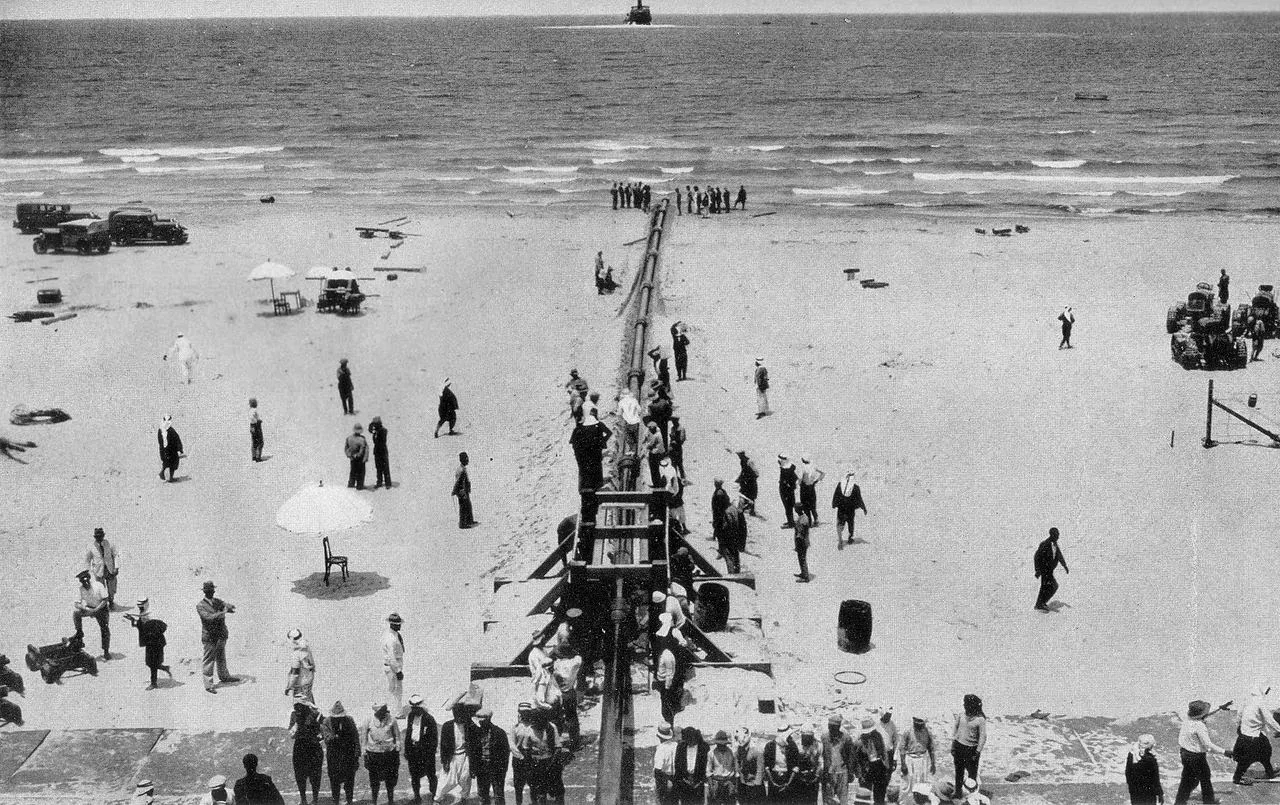

|

| Mosul-Haifa pipeline reaches the coast in 1938 |

“The gradual growth of considerable Jewish community, under British suzerainty, in Palestine will not solve the Jewish question in Europe. A country the size of Wales, much of it barren mountain and part of it waterless, cannot hold 9,000,000 people. But it could probably hold in time 3,000,000 or 4,000,000, and some relief would be given to the pressure in Russia and elsewhere. Far more important would be the effect upon the character of the larger part of the Jewish race who must still remain intermingled with other peoples, to be a strength or to be a weakness to the countries in which they live. Let a Jewish centre be established in Palestine; let it achieve, as I believe it would achieve, a spiritual and intellectual greatness; and insensibly, but inevitably, the character of the individual Jew, wherever he might be, would be ennobled. The sordid associations which have attached to the Jewish name would be sloughed off, and the value of the Jews as an element in the civilisation of the European peoples would be enhanced.

"The Jewish brain is a physiological product not to be despised. For fifteen centuries the race produced in Palestine a constant succession of great men - statesmen and prophets, judges and soldiers. If a body be again given in which its soul can lodge, it may again enrich the world.”— The Future of Palestine

In November 1918 the large group of Palestinian Arab dignitaries and representatives of political associations forwarded a petition to the British authorities in which they decried the hubris of the declaration. The document stated:

“[W]e always sympathized profoundly with the persecuted Jews and their misfortunes in other countries... but there is wide difference between such sympathy and the acceptance of such a nation... ruling over us and disposing of our affairs.”Winston Churchill sided with the Arabs, saying in 1922, “I do not attach undue importance to this [Zionist] movement, but it is increasingly difficult to meet the argument that it is unfair to ask the British taxpayer, already overwhelmed with taxation, to bear the cost of imposing on Palestine an unpopular policy.

|

| Arthur Balfour and his Declaration |

Between 1919 and 1923, 40,000 Jews arrived in Palestine, mainly escaping the post-revolutionary chaos of Russia and Ukraine (the Third Aliyah) where over 100,000 Jews had been massacred. These immigrants were called halutzim (pioneers) because they were experienced in agriculture and quick to establish self-sustaining frontier towns. The Jezreel Valley and the Hefer Plain marshes were purchased through foreign donations, drained and converted to agricultural settlements. A socialist underground militia, the Haganah ("defense") sprang up to defend the outlying settlements.

Despite Palestinian Arab rioting in 1920 and 1922, 82,000 more Jewish refugees had arrived by 1929 (the Fourth Aliyah), fleeing pogroms in Poland and Hungary and rebuffed by the anti-Semitic United States Immigration Act of 1924.

The British governors of Palestine rejected the principle of majority rule or any other measure that would give the Arab population, who formed the majority, control over Jewish territory. The United States, whose strategic objective (oft quoted by comedian Robert Newman in A History of Oil) was “to bring democracy to the Middle East,” supported this policy, and still supports it today.

Following World War II, oil interests in the Middle East tilted western allies towards the Arabs. In an effort to win independence, underground Jewish militias waged a guerrilla war against the British. From 1929 to 1945, 110,000 Jews entered Palestine illegally (Bet Aliyah). Between 1945 and 1948, 250,000 Holocaust surviving Jews left Poland, Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia for refuge in Palestine. Most of these refugees were intercepted by the British and interred in squalid camps in Cyprus. Finally, under pressure from their Arab oil partners, the British had enough, and referred the whole matter to the United Nations.

Following World War II, oil interests in the Middle East tilted western allies towards the Arabs. In an effort to win independence, underground Jewish militias waged a guerrilla war against the British. From 1929 to 1945, 110,000 Jews entered Palestine illegally (Bet Aliyah). Between 1945 and 1948, 250,000 Holocaust surviving Jews left Poland, Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia for refuge in Palestine. Most of these refugees were intercepted by the British and interred in squalid camps in Cyprus. Finally, under pressure from their Arab oil partners, the British had enough, and referred the whole matter to the United Nations. The UN, looking at the status quo on the ground, drew this map, which is probably the worst partition ever conceived.

On November 29, 1947, in Resolution 181 (II), the UN General Assembly recommended a plan to replace the British Mandate with separate "Independent Arab and Jewish States" and a "Special International Regime for the City of Jerusalem administered by the United Nations."

Neither Britain nor the UN took any action to implement the resolution and Britain continued detaining Jews attempting to enter Palestine. The British withdrew forces in May 1948, but continued to hold Jews of "fighting age" and their families on Cyprus until March 1949, anticipating what was about to happen.

What was about to happen was the delivery of the promised utopia to the Jews and a catastrophe for the Palestinians.

To be continued

Comments

It's my understanding that that's the case, and I think that lends a certain irony to the whole sad spectacle.