The Great Pause Week 67: The Social Lives of Forests

"The places of greatest biodiversity are a result of, rather than in spite of, long human disturbance of the environment."

Over the past few weeks we have been taking a deeper dive into biophysics, looking at energy and climate returns on investments in renewables and drawdown tech, landscape restoration, and lifestyle change. Trillionization is well underway, as predicted at the time of the Paris Agreement, but I am not the only one to say most of that money will be scandalously wasted.

During the pandemic, novelist MacKenzie Scott, Jeff Bezo’s ex, gave away $10.7 billion of her settlement to a suite of charities that reduce the wealth and power gaps of the type that companies like Amazon widen, only to discover she made more that twice that much in that same period, thereby widening her personal wealth and power gap. Her ex-husband is much more sensible about getting rid of his wealth — he throws it into outer space where there is no possibility of it ever coming back to make him richer.

We can try to draw lessons from history, but projecting those into an uncertain future never before experienced by hominids is risky, and as MacKenzie Scott learned, this is not your daddy’s money system anymore, either. That said, some things really are eternal, and biophysical economics is one.

When early Europeans first arrived to North America they thought they were in a wilderness. Seeing no roads, cities, or sports arenas (all of which existed farther inland or in other times), they considered the human inhabitants “savage,” uncivilized, and little more than animals that they could perhaps train to perform menial labor.

As we know now, the habitation pattern of the Americas in 1492 was as advanced as anything in Europe then, and although of different design than European municipalities, was perhaps more realistically futuristic than science fiction concepts of glass skyscrapers with flying cars or domed colonies on Mars. But, like the speech of a whale to a whaler, the patterns revealed were incomprehensible to the conquerors, and so dismissed.Had these people and their ideas not been bludgeoned to bloody mist like so many whales, passenger pigeons and buffalo, we could have learned much from their arts, sciences, languages, and phenological observations.

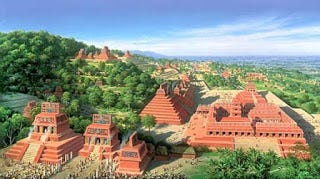

Archaeobiological data are used to explore the agricultural basis of the Jama-Coaque II archaeological culture that inhabited the western coastal lowlands of Ecuador between approximately AD 400 and AD 1430. Analyses of archaeobotanical and archaeofaunal assemblages recovered from 14 archaeological sites throughout the valley implicate an extensive native agroforestry system. The quantitative and qualitative composition of assemblage diversity suggest the accumulation and deposition of restricted categories of plants and animals whose ecologies reveal the possibility of a landscape managed through a form of pre-Columbian agroforestry that combined domesticated annuals, perennial tree crops, and useful forest taxa.

— Stahl and Pearsall 2012

What Magellan, Raleigh, Drake, Cabeza de Vaca, Cartier, Coronado, DeSoto, Cabot, Hudson, Gilbert, Smith, Cook and Zheng He discovered in the Age of Discovery were not wildernesses (as they reported to their respective monarchs) but subtle, extremely productive, and advanced human ecologies. Through the cultivation of landscape, First Nations shaped their environments to be continuously abundant, enduring, and interconnected. They observed the natural productivity of a landscape, tweaked it slightly to make it more friendly, and lived within, rather than against it.

Of course, there were cases where thoughtless or ill-conceived human activities reduced biodiversity. We have fossil and historical records of the extinctions of megafauna. Yet many native landscapes preserved today in remote areas or national parks, and appreciated for their high biodiversity, provide scientific evidence of human use and respectful management over millennia. To quote one archaeological study of the Amazon basin, the places of greatest biodiversity “are a result of, rather than in spite of, long human disturbance of the environment.” What the original inhabitants began with was often less productive and biologically diverse than what resulted but the final products of generations were exquisitely elegant.

|

The Lost Colony, design by William Ludwell Sheppard, engraving by William James Linton. |

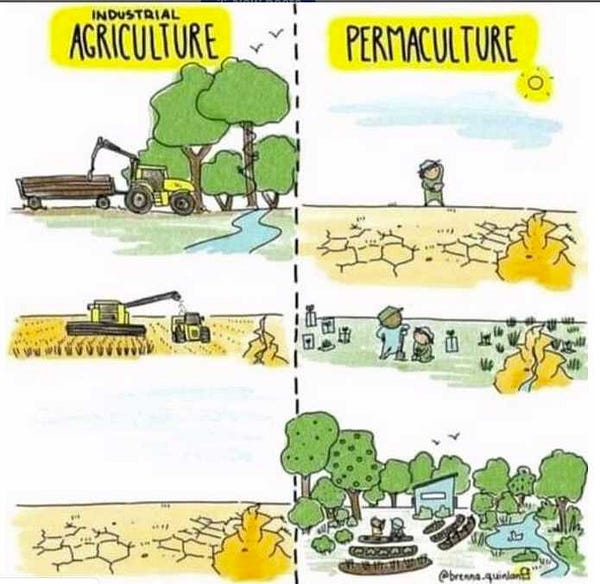

In Amazonia: the historical ecology of a domesticated landscape, Clark Erickson explained how the land use practice Europeans called “slash and burn” actually worked:

Slash-and-burn agriculture is characterized by low labor inputs, limited productivity per land unit, and short period of cultivation followed by longer periods of fallow or rest. … In addition to basic food crops, useful fruit and palms are often transplanted to the clearing. As fields fall out of cultivation because of weeds and forest regrowth, the plots continue to produce useful products, long after “abandonment”.

In 2007, while in Manaus to attend a conference on the terra preta soils, I paid a call at the university to meet Charles Clement. The professor was a man about my age, thin, with greying hair, who, just before our interview, had been busy taking pollen samples and radiocarbon dating them to better understand the ancient human influence on successional tropical forests.

I came to better appreciate his work when, after teaching a permaculture design course to a Kuna group in the Darien Peninsula of Colombia, I bouldered a steep river bed through dense forest for several miles before arriving at a mountain valley lush with fruit trees and many understory food and medicinal plants. It had not been humans that had planted this, or “nature” in a limited sense, but the monkeys who now tended and renewed their garden as they swung from tree to tree, harvesting calories and defecating seeds.Similarly, in many indigenous cultures, local farmers’ perception of cultivated and wild is not separated by a bright line. Erickson explains:

Anthropogenic forests are filled with fruit trees, an important component of agroforestry. Eighty native fruit trees were domesticated or semi-domesticated in Amazonia (Clement 2006). Fruit trees, originally requiring seed dispersing frugivores attracted to the juicy and starchy fruits, became increasingly dependent on humans through genetic domestication and landscape domestication for survival and reproduction. In addition, humans improved fruit tree availability, productivity, protein content, sweetness, and storability through genetic selection. Oligarchic forests, characterized by a single tree species, often a palm, provide mass quantities of protein and building materials, and food for the game animals. In the Bolivian Amazon, thousands of kilometers of the burití palm, the Amazonian tree of life, contributes protein and materials for buildings, basketry, weapons, and roofing. Forest islands of chocolate trees are agroforestry resource legacies of the past inhabitants of the region.

Agroforestry and rotational milpa — patch clearance and regeneration — draws in and nourishes game animals that become another source of protein, fiber, and hides. Their decaying dung and processed bone and blood become fertilizer, transporting minerals from areas of abundance to areas of scarcity. For this reason, it is common for indigenous peoples to “plant for the deer;” to grow more food than necessary in order to attract and nourish game. They cultivate more than corn. They cultivate an ecology.

As a result, “garden hunting” is particularly efficient. Many game animals of Amazonia would have a difficult time surviving without a cultural and historical landscape of human gardens, fields, orchards, and agroforestry. The biodiversity of animals can also be enhanced by domestication of landscape. In coastal Ecuador, Stahl (2000, 2006) reconstructs biodiversity and the character of the anthropogenic environment through the remains of diverse animals in garbage middens of 4,000-year old settlements. The majority of identified animals thrive in a disturbed mosaic environment with light gaps, edges, old gardens and field clearings.

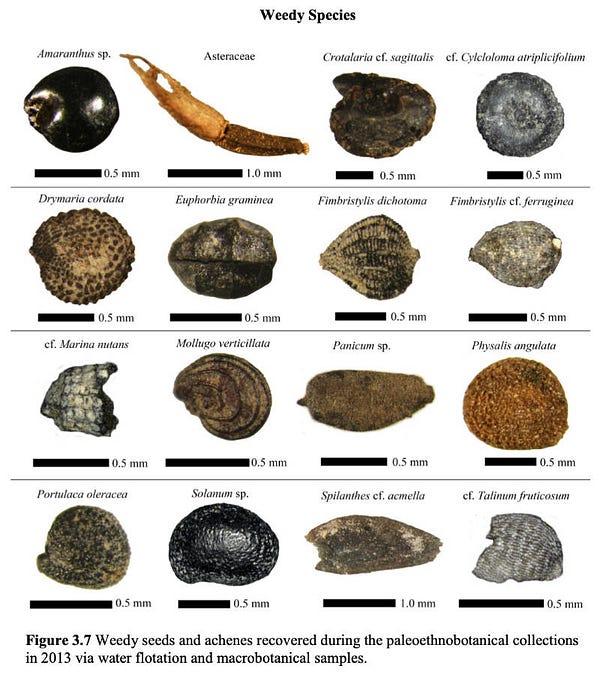

A 2013 dig at the Classic Maya archaeological site Joya de Cerén in El Salvador focused on the analysis of plant remains near a sacbe (causeway) that were preserved under volcanic ash around AD 650. Finding agroforestry guilds, biochar fertilizers, and traditional maize, squash, agave and bean varieties was not surprising, but the researchers scratched their heads at the abundant “weeds.” It had been previously thought that the Cerén residents had well-maintained agricultural fields with few weeds or intrusive plants present among their annual crops.

Various theories were advanced and discarded: the weeds were post-Conquest (ruled out by dating); they were were persistent perennials (they were not); they indicated change in soil fertility (not supported); lack of labor available to remove weeds with wooden and stone tools (no indication). Of the 16 different weedy species recovered (image), the majority are actually annual plants that would have been relatively easy to manage, if so desired. The study concluded:

Perhaps the paleoethnobotanical results from Cerén suggest a difference in the way weedy plants were conceptualized by the ancient Maya compared to modern views on the plants. According to Steggerda (1941), the main goal of agriculture in the Yucatan was to “use the land constantly and keep it covered, as far as possible, with useful plants instead of with useless weeds.” Alternatively, the species referred to as ‘weeds’ in this study may have been viewed quite differently by the ancient Maya than they are by people today. The plants were not necessarily seen as useless materials to the Cerén residents. The gathering of tolerated weedy species considered edible, or quelites, is a common supplement to Milpa agricultural systems.***The act of weeding an agricultural field is not an emphasized portion of the agricultural cycle in Kekchi villages in Belize (Wilk 1997). There, weeding is a casual side job when doing something else and is generally only a focus on when a particularly dangerous variety of weed is present, such as those with thorns or spines. The Kekchi Maya do not view weeds as a threat to crops once they have already begun growing and therefore their removal would be futile.***Stepp and Moerman (2001) have shown that the Tzeltal Maya in Chiapas actually utilize a high frequency of weedy species for medicinal purposes. … All of the weedy species recovered from Cerén have known uses nutritionally, medicinally, or for other purposes. Farmers have a tendency to design a system of farming that yields the highest return per hour of work (Sanders 1973: 332) and collecting materials from the useful shrubs growing in the milpa may have been a way to increase the rate of return. Unfortunately, the contexts in which the Cerén samples were collected cannot verify that the Maya were aware of these uses for the weedy plants, but their strong presence suggests they held positive relationships with the villagers where they were certainly tolerated.

One creature’s weed is another’s manna. To lawn care addicts, milkweed is a noxious invasive. To migrating monarch butterflies, it may spell the difference between survival and extinction. Humans were an equal partner in the ecology of Cerén and the burití palm forests of Bolivia. Perhaps our role is to plant and harvest, or perhaps it is merely to observe and record. Either way, once humans are removed, the system is diminished.

That is really the open secret of climate solutioneering. Despite desperate searches by X-Prize, Gates, the Bellona Foundation, and many others, the way out of this has been hiding in plain sight.

If we plant monoculture forests of pine or eucalyptus to pelletize and feed gigawatt-scale power stations, we will lose soils, microbes, all the forest creatures, and part of our own humanity. We can manufacture forests of aluminum trees in Iceland but the amount of CO2 they’d withdraw in a century might be less than is produced by a single volcanic eruption. Then, too, we’d want to ask how much CO2 went into producing metals, rare earths, and chemical catalysts for those devices. We can pave the plains with solar PV, elevated on poles to allow for shaded alley crops and grazing animals, but the tempests to come make that scheme vulnerable and once more, there would be questions of EROI and depleted non-renewables.“Where are the supersonic aircraft? Where are the millions of delivery drones? Where are the high speed trains, the soaring monorails, the hyperloops, and yes, the flying cars?”

— Mark Andreessen in April 2020, refuting the idea of a damaged post-pandemic global economy.

But once we begin to speak of mixed-age, mixed-species forest ecosystems with humans included, all that changes. Take away the herbicides and pesticides. Add chinampas, marine permaculture, rooftop and vertical gardens, and eradicate food waste — we can still feed the world.

Estimates of the decline of the native human population of the Americas over the first century and a half following the Columbian Encounter range from 80 to 99.2 percent — from 50 to 1000 million in 1492 (estimates vary) to approximately 8 million in 1650 (and still fewer in later centuries) — caused by outbreaks of Old World diseases, slavery, and violent ethnic cleansing. As unspeakable as was the infliction of atrocities of such magnitude on the human population, far greater was the all-out assault on biodiversity imposed by the switch to “modern, civilized, progressive” land use practices and agrochemistry.

The self-inflicted biodiversity loss carries a punishment proportional to the crime.

|

Bill Gates’ nuclear yacht, Earth 300 |

References

Ambrósio Moreira, P., Mariac, C., Zekraoui, L., Couderc, M., Rodrigues, D.P., Clement, C.R. and Vigouroux, Y., 2017. Human management and hybridization shape treegourd fruits in the Brazilian Amazon Basin. Evolutionary Applications 10(6), pp.577–589.

Bardi, Ugo, Sara Falsini, and Ilaria Perissi. “Toward a general theory of societal collapse: a biophysical examination of Tainter’s model of the diminishing returns of complexity.” BioPhysical Economics and Resource Quality 4, no. 1 (2019): 3.

Barton H., Denham T., Neumann K., Arroyo-Kalin M. 2012. Long-term perspectives on human occupation of tropical rainforests: An introductory overview, Quaternary International, Volume 249.

Belsky, J.M., 2017. The Social Lives of Forests: Past, Present, and Future of Woodland Resurgence, by Susanna B. Hecht, Kathleen D. Morrison, and Christine Padoch, eds. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Crutzen, P. J. and W. Steffen. 2003. How long have we been in the Anthropocene era? Clim. Change 61, 251–257.

Erickson, Clark L. 2008 “Amazonia: the historical ecology of a domesticated landscape” in The Handbook of South American Archaeology, pp. 157–183. Springer, New York.

Iriarte J., Elliott S., Maezumi S.Y., Alves D., Gonda R., Robinson M., Gregorio de Souza J., Watling J., Handley J., 2020 The origins of Amazonian landscapes: Plant cultivation, domestication and the spread of food production in tropical South America, Quaternary Science Reviews, Volume 248.

Odum, Howard T., and Elisabeth C. Odum. “The prosperous way down.” Energy 31, no. 1 (2006): 21–32.

Sanders, W. 1973 The Cultural Ecology of the Lowland Maya: A Re-evaluation, in The Classic Maya Collapse, ed. T. P. Culbert, pp. 325–336. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Slotten, V.M., 2015. Paleoethnobotanical remains and land use associated with the sacbe at the ancient Maya village of Joya de Cerén (Doctoral dissertation, University of Cincinnati).

Stahl, P.W. and Pearsall, D.M., 2012. Late pre-Columbian agroforestry in the tropical lowlands of western Ecuador. Quaternary International, 249, pp.43–52.

Steggerda, M. 1941 Maya Indians of Yucatan. Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication 531.

Stepp, J. R. and D. E. Moerman 2001 The importance of weeds in ethnopharmacology. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 75: 19–23.

Tainter, Joseph, The Collapse of Complex Societies. London: Cambridge University Press (1988).

Wilk, R. R. 1997 Household Ecology: Economic Change and Domestic Life Among the Kekchi Maya in Belize. Northern Illinois University Press, Dekalb, Illinois.

___________________

The COVID-19 pandemic has destroyed lives, livelihoods, and economies. But it has not slowed down climate change, which presents an existential threat to all life, humans included. The warnings could not be stronger: temperatures and fires are breaking records, greenhouse gas levels keep climbing, sea level is rising, and natural disasters are upsizing.As the world confronts the pandemic and emerges into recovery, there is growing recognition that the recovery must be a pathway to a new carbon economy, one that goes beyond zero emissions and runs the industrial carbon cycle backwards — taking CO2 from the atmosphere and ocean, turning it into coal and oil, and burying it in the ground. The triple bottom line of this new economy is antifragility, regeneration, and resilience.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

#GenerationRestoration

“There are the good tipping points, the tipping points in public consciousness when it comes to addressing this crisis, and I think we are very close to that.”

— Climate Scientist Michael Mann, January 13, 2021.

Want to help make a difference while you shop in the Amazon app, at no extra cost to you? Simply follow the instructions below to select “Global Village Institute” as your charity and activate AmazonSmile in the app. They’ll donate a portion of your eligible purchases to us.

How it works:

1. Open the Amazon app on your phone

2. Select the main menu (=) & tap on “AmazonSmile” within Programs & Features

3. Select “Global Village Institute” as your charity

4. Follow the on-screen instructions to activate AmazonSmile in the mobile app

Comments

It is absolutely Not the Time to Build, but the time for renewal and revision. The time to build (if we make it that far) will be in another 25 years.

You've got it right, Albert. Time to Plant (forest gardens) is more apt.