The Great Pause Week 42: Taintered Passages

Desiderio Hernández Xochitiotzin, Murales de Tlaxcala

Covid should make us aware, however, of the potential for a novel virus or some other lethal infectious agent to bring global civilization to abrupt collapse; full stop. Had vaccines not been discovered, and had natural disasters simultaneously combined to produce widespread famines, this pandemic might have resembled the Black Death or a similar historic collapse that can unfold more rapidly than herd immunity can develop. Because Covid is only lethal in a small number of cases compared to those that are mild and confer immunity, however, a full-on collapse comparable to the fall of Rome in the 6th century or the feudal system in the 14th was never likely. Nonetheless, the zoonotic potential remains for that destiny to be fulfilled in our lifetimes.

A full scale SolarWinds cyberattack could have met Diamond’s defined threshold for collapse. It might still.

Last month I looked at the writings of environmental sociologist William R. Catton. This week I’ll dive into a parallel stream developed by the other scientist I sat down next to in that row of fold-down auditorium seats in DC on a brisk May day in 2006: anthropologist Joseph Tainter, author of The Collapse of Complex Societies (1988).

By studying the collapse of a number of monumental civilizations, Tainter teased out many causes of collapse and how they combine in synergistic ways. His analysis is illuminating when one tries to parse how nations like the US, UK and Sweden were laid low by Covid while others, like Iceland, Senegal, and New Zealand, sailed through nearly unscathed.

Collapse is seldom entirely the result of external or natural forces. Most often it comes from latent social forces, or entropies, that are brought to crisis by some triggering event. Iceland, Senegal, and New Zealand are tight-knit cultures with deep reserves of social capital. When New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern called upon her “team of 5 million” to go into voluntary lockdown, they went, even if somewhat grudgingly, until they saw what following the advice of epidemiologists had got for them compared to other countries, and then the grudges wore off. In Senegal, graffiti artists painted Covid murals on city walls, warning the population to mask and supporting healthcare personnel. In the USA and a number of other countries, the inferiority of pay-to-play health care systems, deep-seated racial and social inequality, absence of rumor control and rational leadership, and many other, by now well-commentated flaws, ran up death tolls needlessly. Recklessly.

The end of the Covid pandemic, which at this writing is still a ways off into the future, will not be the end of the problems it exposed. Knowing about them does not equate to doing something about them. By largely ignoring them, as we are predisposed towards, we set ourselves up for still greater calamities to come. One of Tainter’s contributing factors is obstructed feedback.

When you fire the head of your Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency and put in a lackey, you have no feedback to tell you that most of the Fortune 500 companies and half the government agencies have been breached by a hack attack of unknown origin, and so it can go on for months, quietly seeding malware.

I am writing this just as BREXIT is playing out upon the European stage even as the Covid pandemic rages across the UK and Northern Europe, graduating into its first Northern winter. Iceland, Senegal, and New Zealand may seem remote, economically, but they are hopelessly tethered to what happens elsewhere because all depend heavily on imports and exports.

In 2019, Iceland’s trade deficit amounted to around a billion euros. In 2020, its exports decreased 5.6 % while imports increased 7.5 %, which must have been a strain, except that since the financial implosion of 2008 they have become accustomed to running annual trade deficits and their lenders have tolerated it. Senegal is a net exporter of oil, phosphate, gold and fish. However, the country is dependent on the import of fuels, foodstuffs and capital equipment. Its sales from mineral, oil, and ocean exploitation are not able to keep pace with the demands of its growing population, causing a persistent trade deficit of 500 million. New Zealand’s trade sheet is always predictably seasonal — surpluses of 300 to 500 million in summer and fall; deficits of 800 million to a billion in winter and spring. Although its exports were down 4.4% in 2020, its imports were down an even greater 12.6%, so it managed austerity well (kudos again to Jacinda Ardern). It would be difficult to find a correlation between trade balance and pandemic response among these examples, but it is not difficult to say that all of these countries are fully integrated into the global economy and will be equally affected by what comes next.

So, what does come next? Tainter would likely say all of the nations in the world today, and their integrated network, can be described as “complex” societies. Complexity requires a substantial caloric subsidy to be maintained, which can be denominated in fossil energy, consumption of resources, or other forms of wealth.

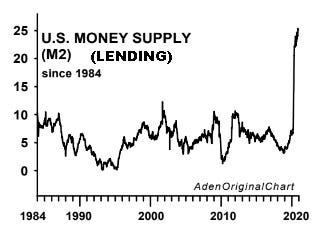

When a society confronts a “problem,” such as a devastating pandemic, it tends to create new layers of complexity to address the challenge, whether within existing agencies or by creating entirely new ones. Operation Warp Speed to develop a vaccine is an example of a new layer, and it was far more complex than, for instance, the Apollo moon landing program, in terms of numbers crunched, persons employed, or moneys spent. The physical resources required were “borrowed” in the sense that the US issued Treasury bonds (which the Fed purchased), and the European Central Bank or the Bank of China did the equivalent, and they lent the money to governments, companies, or consortia to produce results. While there was little immediate drawdown of real calories from food inventories, oceans, or oil refineries, these bonds were IOUs for future calories. The world went into caloric debt to fund Operation Warp Speed and all other parts of the pandemic response.

This entire exercise laid bare the hoax being perpetrated by politicians who claim there is no money to pay for a Green New Deal to address the climate emergency, because the trillions borrowed to respond to the Covid crisis were far more, cash wise, than anyone had dreamed of asking for to begin pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere by safe natural means, or by sponsoring the experimental phase of new carbon drawdown economy. Still, borrowing from the future to spend now always carries consequences. Sooner than you expect, those debts come due.

Such debts are of little concern in a period of rapidly expanding resources, such as following discovery of two entire continents, each larger than Europe, populated only by inhabitants without gunpowder, Andulusian war horses, Toledo steel or any natural immunity to measles; or in 1595 in Balakhani, Azerbaijan, when Allah Yar Mammad Nuroghlu dug a 35m deep well to extract black oil, forever altering the balance of sunlight calories bouncing back to space or stored within our planet’s rock, by Watts per square meter as it turned out. It is only when such one-off expansions of carrying capacity begin to contract that debts to the future intrude and creditors come knocking.

In Collapse, Tainter identifies seventeen examples of rapid collapse and applies his model to three case studies: The Western Roman Empire, the Maya civilization, and the Chaco culture.

As Roman agricultural output slowly declined and population increased, per-capita caloric availability dropped. The Romans “solved” their deficit not by borrowing but by investing in their military and expanding. They conquered their neighbors to gain more grain, metals, slaves, and armies. However, as they grew, the cost of maintaining supply lines, communications, garrisons, civil government, etc. grew faster. Eventually, as their currency devalued and their overstretched borders were overrun, the Romans learned lex minoratio redit — the law of diminishing returns. Hitler sent armies into Poland and Czechoslovakia for the same reason — too many people on too little land — and began strategic exterminations in conquered territories to make room for future Aryans. He followed Caesar’s dictum but neglected to read up on lex minoratio redit.

Complexity by itself produces diminishing returns. Conquest can be counterproductive, and as we saw last week, civilizations more often fall by their own hand — by neglect of the ecosystems that support them.

Terminal stages have many common elements. Shortages in things like land close to to urban centers drive up real estate prices, displacing service classes, which drives wage demand, illegal immigration, and poverty. Military conflict over depleting resources militarizes society at home. Intense, authoritarian efforts to maintain cohesion foster push-back by the oppressed populations. General strikes. Populist demagogues. Cabals. Elite escape refuges. There is seldom a catastrophic die-off; more often there is merely a fragmentation. In both the Mayan and Roman collapses, the welfare of the people improved by a devolution to rural simplicity. Tainter is not entirely a pessimist. While the cycle itself cannot be thwarted, he believes innovation can stave off the worst parts of contraction phase.

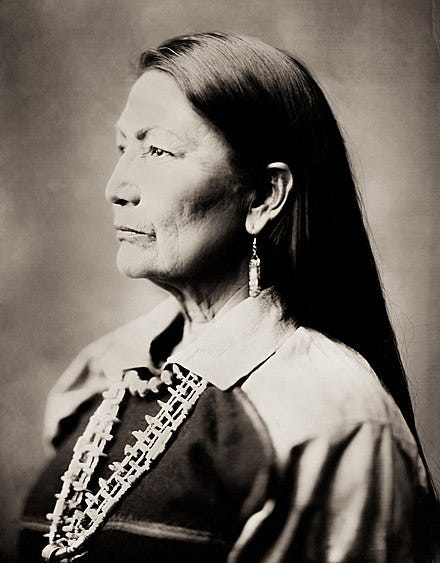

Joe Biden’s pick for Interior Secretary, Debra Haaland, is 35th generation Laguna Pueblo. Her very existence is proof that the collapse of Chaco culture did not augur extinction of the Pueblo peoples. If the Senate runoff election in Georgia goes well enough for her to be confirmed, Haaland will oversee about one-fifth of the land in the United States, 476 dams and 348 reservoirs, 410 national parks, monuments, seashore sites, 544 national wildlife refuges, much of Alaska, and the well being and demands of 574 federally recognized tribes, Hawaiians, Native Alaskans, Pacific Islanders, and the populations of other occupied territories that have been engaged in an unfulfilled civil rights, land and water struggle since at least the mid-1950s.

Harvard Lampoon cartoonist and Hasty Pudding cross-dresser Jorge Agustín Nicolás Ruiz de Santayana said, “those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” While the pandemic of 2020–21 did not bring with it the collapse of complex civilization, it was one more small nail in an already fashioned coffin. A harbinger, if we care to notice.

This holiday season let us rejoice that we were bowed but not broken by the calamities that beset us in 2020. We have been given a learning moment. Pray we will use it.

_____________

The COVID-19 pandemic has destroyed lives, livelihoods, and economies. But it has not slowed down climate change, which presents an existential threat to all life, humans included. The warnings could not be stronger: temperatures and fires are breaking records, greenhouse gas levels keep climbing, sea level is rising, and natural disasters are upsizing.

As the world confronts the pandemic and emerges into recovery, there is growing recognition that the recovery must be a pathway to a new carbon economy, one that goes beyond zero emissions and runs the industrial carbon cycle backwards — taking CO2 from the atmosphere and ocean, turning it into coal and oil, and burying it in the ground. The triple bottom line of this new economy is antifragility, regeneration, and resilience.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

Comments