The Great Pause Week 38: Corn Science Objectors

"There are no simple answers, only simple questions."

During the 2020 US election cycle, which now seems so long ago, a televised virtual debate took place in the State of Iowa. The incumbent Senator, Joni Ernst, first gained national attention in 2014 for a televised campaign ad comparing the castration of hogs to cutting spending in Washington. “Let’s make ’em squeal,” she proclaimed.

Her reputation was then cemented when she delivered the opposition party response to President Obama’s State of the Union Address in 2015, introducing herself to the nation ”as a young girl [who] plowed the fields of our family farm.”

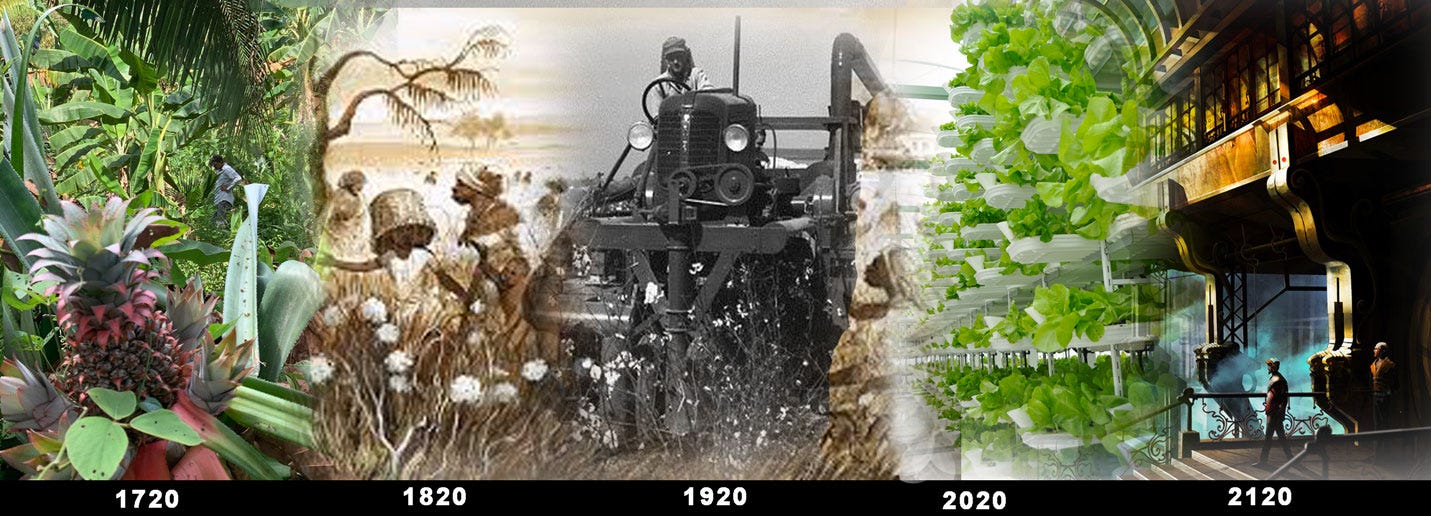

Iowa‘s deep grassland soils churned out an abundant supply of corn and wheat for two centuries until the advent of chemical fertilizer, which destroyed soil fertility at an historically unprecedented rate — far faster than in the wasting of the Fertile Crescent of Mesopotamia or the Nile Valley in the time of the Pharaohs. About 90 percent of Iowa’s surface area is dedicated to farming, but its real wealth lay below that, in the meters of black earths built by eons of grazing and manuring buffalo, lightning strikes, and glacier ebbs and flows.

Today the state’s top 5 agricultural products, in order of cash receipts, are corn, hogs, soybeans, cattle and dairy. So, it came as no surprise that a candidate for statewide office would be asked about the casuistry of commodity prices. Ernst’s challenger, Democratic candidate Theresa Greenfield, who also grew up on a farm, was asked to estimate the “break-even” price of corn.

“It’s going for about $3.68, 3.69” Greenfield said, reciting from memory the latest per bushel price on the Chicago commodities exchange. She added that “break-even” would depend on how much debt a farmer was carrying.

Turning to Ernst, the moderator asked the same question about soybeans. The Senator answered $5.50, well below the actual price of $10.05. Soybeans had not sold for $5.50 per bushel since 2006. They had not sold below $8.50 since mid-2007. Although Ernst won the election a few weeks later, the misstep was a political setback for her at the time and probably cost her some votes.

The underlying story, a tale of lost fertility and lock-in consumer addiction, with Earth’s climate and human extinction hanging in the balance, is far more interesting.

Let’s begin with the price of a bushel of corn. The reference bushel — not whole corn, cob and all, but shucked kernels — weighs 55 pounds or 25 kg. A homesteader farm family in 19th century Iowa would perhaps spend 100 man-hours, on average, to till, sow, cultivate, harvest, transport, shuck, store seed, and cover crop to obtain each bushel. There might be variations in output depending on the quality of land, rainfall, whether the family had a horse or mule, whether they owned a mechanical shucker, and so forth, but chances are the fertilizer was applied by a family cow browsing the stalks in the field in the winter and there were no bank loans involved in operating the farm. Certainly the same would be true for the indigenous peoples — Ho-Chunk/Winnebago, Missouria, Otoes, Kaw, Omaha, Osage, Ponca, Hidatsa, Ioway/Baxoje, Mandan, Dakota, Arikara, Pawnee, Shawnee, Illinois, Kickapoo, Paoute, Mascouten, Meskwaki, Sauk, Wyandot,Potawatomi, Ojibwe/Chippewa, Odawa, and Comanche — for whom bank loans, machines, and chemicals would have been alien concepts when it came to planting corn.

Of course, 100 hours labor for $3.68 would have been a real bargain for the corn’s consumers, but money did not always change hands. Part of the harvest, or even all of it, never left the family farm. Even in years when it was not profitable to sell, the corn could be fed to livestock and/or made into cornbread and porridge. The price of Iowa corn in 1898 was $0.29/bu, or $8.99 adjusted to today’s dollar. Today the bushel price is half that, thanks to industrialization of agriculture.

In 1898, no one used corn to make floor wax, plastic toys, diapers, or drywall. It was too valuable. It was food. It took the Green Revolution of the 20th Century to turn it into the ubiquitous material feedstock we know today.

Before the 20th Century it was not a normal routine to transport and sell the part of a crop needed to be saved for seed for the following year to a grain storage elevator, and to use a portion of those receipts to pay off a bank loan so you could take another loan to buy the seed back from the elevator when it was time to plant again. Of course, all of that was made possible by cheap fossil fuels that allowed large grain trucks to travel to and from every farm and for silos to dehydrate the grain with hot air blowers. No one paid for the damage to the atmosphere.

By far the best book I have read on the Green Revolution is The Wizard and the Prophet by Charles Mann. It tells the story through the careers of two individuals. Norman Borlaug worked relentlessly to start the revolution, for which he won a Nobel Prize in 2005. William Vogt was one of the original thinkers behind the environmental movement, at one point the director of Planned Parenthood, and a strong proponent of population control and rewilding. They lived at the same time, looked at the same problems, even met once, but came to opposite conclusions about what was needed. Vogt was a ‘prophet’, averring that technological solutions are ultimately hubris, that humanity should try to live in harmony with nature, scale back, and strive for sustainability and regeneration. Mann means ‘prophet’ in an almost derisive sense — the old man in the sackcloth and sandwich boards railing against the sins of the world. History may well prove Vogt a prophet in the other sense — a man well ahead of his time, accurately forecasting what would later come to be.

Borlaug was a technophile. He found ready support from the Rockefeller Foundation and many governments for his cornucopian vision of a limitless human prospect. He almost never wanted for funds to carry out large scale projects and was in part responsible for spreading to factories around the world the Haber-Bosch process of making nitrogen, rapidly hybridizing seed into genetic monocultures, and modernizing agriculture to resemble an automotive assembly line.

Once you understand the concept of carrying capacity, it becomes clear that there are two ways of addressing the problem of finite natural resources. One is to limit population growth and improve the efficiency (reduce waste) of resource utilization. The other is to artificially increase the availability of resources, for example by using science to increase crop yield. But physics is a zero-sum game, and so, therefore, is biology. A sudden benefit to one species is an assault on another. Chemical production of nitrogen unemploys nitrogen-transforming microbiota, effectively sterilizing soil. As farms lose those bacteria they also lose an entire food chain, an unseen ecosystem, and also the myriad unrecognized benefits other elements of that system provide and receive. In place of the natural world, the product of co-evolutionary processes of billions of years, you get a mechanical laboratory experiment, made possible only by the one-off abundance of cheap fossil energy and the reliability of a benign climate.

Borlaug assumed that once oil ran out, and it was by no means certain in the 50s and 60s when his revolution was unfolding that oil would ever run out, it would be replaced by some other technological leap — fusion perhaps, or genetically engineered biofuels. The balance that held back these alterations was derided as limits to growth, which were inconceivable. His vision was blinkered by the seeming success of the industrial revolution.

Social costs went unnoticed. Chemical fertilizers, GM seed, herbicides, and pesticides work miracles in the first few years they are applied, multiplying crop yields and cutting labor costs for those who can leverage large bank loans and hope the weather cooperates. These chemicals come with a suite of mechanical devices that favor more massive farms. When banks foreclose, small farmers are dispossessed, fenceposts are knocked down and fields are graded for the larger players with larger machines.

Government policies encouraged farms to make the switch, as Borlaug intended, but once the fiscal casino owners were in the system, the newly-minted large farm owners found themselves on a financial treadmill. Each year newer machines, more chemicals and patented seed were needed just to keep production stable. Sterilization of soil, favorable conditions for weeds and predatory insects, and mounting debt to lenders compelled even large farmers to default and banks to foreclose and sell to corporate operators. Generational patriarchs committed suicide and lands became no longer productive enough for further investment. Even a fair amount of good lands were abandoned to residential and commercial sprawl to pay inheritance taxes. That was the epidemic Borlaug unwittingly unleashed. Vogt had predicted it.

If you believe consumer affluence is the goal and science and technology have the answers, you’re with Norman Borlaug and the wizards. But there are no simple answers, only simple questions. While science and technology can speed energy throughput to increase food production, there are always costs. Speeding energy throughput speeds entropy. The Green Revolution has done more than destroy farmland and dissolve family farms. It is concentrating financial wealth, driving species to extinction, warming the planet, depleting non-renewable resources, acidifying the oceans, damaging the ozone, and wrecking vast ecosystems beyond easy recovery.

Likewise, while conservation and environmental protection programs have been valuable, by themselves they have never been able to compete with planet-destroying human impulses for a very simple reason: they don’t produce the food or energy needed to supply the ever-expanding global population of humans. Which introduces us to the central player in this tragedy.

Next week we will take a closer look at an Amish farmer in Ohio named John Eli Miller. The Amish take their name from the protestant reformer Jakob Ammann (1644–1712) who broke away from the Swiss Brethren movement and required his followers to “forsake the world” by practicing separation not only from mainstream society, but from more lenient divisions of the Anabaptist Christians, such as Mennonites and Hutterite Brethren. Ammann stood opposed to long hair on men, shaved beards, and clothing that manifested pride. He demanded social avoidance — shunning — of those who had committed offenses such as lying or prideful behavior. He insisted on conscientious objection to military service. Today we associate the Amish with their limited use of power-line electricity, telephones, and automobiles, as well as their distinctive “plain” clothing. Ammann did not, however, insist on moderation in family planning and for that reason, the 350,665 present-day members of Old Order Amish churches in North America — up from 166,500 in 2000 — are experiencing a farming crisis in 2020.

While they would have differed mightily on issues of technology and finance, on the question of human population, Borlaug had much in common with Miller.

_________________________________

The COVID-19 pandemic has destroyed lives, livelihoods, and economies. But it has not slowed down climate change, which presents an existential threat to all life, humans included. The warnings could not be stronger: temperatures and fires are breaking records, greenhouse gas levels keep climbing, sea level is rising, and natural disasters are upsizing.

As the world confronts the pandemic and emerges into recovery, there is growing recognition that the recovery must be a pathway to a new carbon economy, one that goes beyond zero emissions and runs the industrial carbon cycle backwards — taking CO2 from the atmosphere and ocean, turning it into coal and oil, and burying it in the ground. The triple bottom line of this new economy is antifragility, regeneration, and resilience.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

Comments