The Great Pause Week 18: Midwinter Down Under

As difficult as coming to terms with living through an all-out global pandemic is, the looming near-term human extinction event that is rapid climate change has not gone away. We have to still keep our eye on the ball.

This pandemic will eventually pass into history. After all, we have had worse years. A volcanic eruption in Iceland in early 536 cast so much ash that the world went into 24-hour darkness for two years, with failed crops and spreading famine, and then a decade of record cold, and an outbreak of bubonic plague carried by fleas from starving rats that took almost half of the Byzantine Empire — 100 million dead.

Earth’s changing climate will forever change our future. And that assumes we can survive it. But like the pandemic, our best hope lies in prevention. Once it takes on a life of its own and gets beyond mere human control, that’s when things get bad. Joe Biden, who hopes to be the next POTUS, says we have 9 years to turn it around. That is childishly optimistic, but on the other side, his opponent says the threat is not even real; another Chinese hoax like the Kung Flu.

Tomorrow, July 17, I will be giving a talk in Cairns, Queensland, at the Australia New Zealand Biochar Initiative’s 4th Annual Conference and 2d Annual Study Tour. I won’t be teleporting there, needless to say, and bandwidth here in rural Mexico is too limited to depend upon for a live presentation via web, so I made a short video and biked over to a hotel yesterday to upload it.

Tomorrow, July 17, I will be giving a talk in Cairns, Queensland, at the Australia New Zealand Biochar Initiative’s 4th Annual Conference and 2d Annual Study Tour. I won’t be teleporting there, needless to say, and bandwidth here in rural Mexico is too limited to depend upon for a live presentation via web, so I made a short video and biked over to a hotel yesterday to upload it.

The video begins with a short walkabout through the construction zone that is my present home. Two weeks ago I started replacing my roof in anticipation of a stronger than normal hurricane season and the likelihood I may have to shelter in place rather than evacuate to some dangerously overcrowded hall of cots in an inland city.

I have taken off the aged palm thatch and replaced it with biochar-enriched superferrocement. As I write this, we are painting the new roof and applying a marine varnish. My home also serves as my office, and before the pandemic struck my attention was centered on our prototype Cool Lab in Belize, where I was working until March 15. When borders started to close, I had three choices where to spend these coming quarantine years: Maya Mountain Research Farm in Belize; Isla Holbox, Mexico; or The Farm ecovillage in Tennessee. I threw the Ching and here I sit.

Let me say a few more words about the Cool Lab. This is the pitch I am giving in Australia. Our Cool Lab project will attempt to demonstrate a carbon-dioxide removal (climate positive) microenterprise hub for the economic development of a rural Maya community in Belize’s Southern Toledo District, bordering Guatemala’s Petén region. The village is in mountain foothills along a river, and for many years has been receiving a steady influx of refugees from neighboring Guatemala, where a combination of bad governance and rapid climate change is uprooting many people in the highlands. They are leaving to avert starvation.

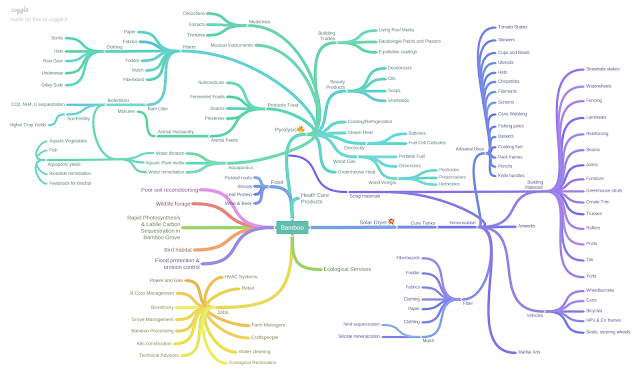

Our Cool Lab is a biorefinery. It will use hydrolysis and pyrolysis to turn woody wastes from local agroforestry (and also potentially dried biosolids from a village-scale sewage plant) into products and services we call a carbon cascade. The cascade might include leaf-protein fractionation from leafy wastes, electric production from coconut coir, rice husk, nut shells, and cacao pods, and novel drawdown commodities like wood vinegar distillates, and biochar in various forms fit for purpose. We might make densified wood shipping containers from bamboo, infused with home-brew bio-oil preservative. We might produce outdoor furniture and biochar-infused roofing tile from a separated stream of plastic waste.

Our Cool Lab is a biorefinery. It will use hydrolysis and pyrolysis to turn woody wastes from local agroforestry (and also potentially dried biosolids from a village-scale sewage plant) into products and services we call a carbon cascade. The cascade might include leaf-protein fractionation from leafy wastes, electric production from coconut coir, rice husk, nut shells, and cacao pods, and novel drawdown commodities like wood vinegar distillates, and biochar in various forms fit for purpose. We might make densified wood shipping containers from bamboo, infused with home-brew bio-oil preservative. We might produce outdoor furniture and biochar-infused roofing tile from a separated stream of plastic waste.

Because we have social and ecological goals, we are in the stage now of detailed surveys of the region — biodiversity, economic and demographic metrics, environmental issues, and cultural norms and preferences — to later serve as our baseline metric. And, because drawdown and climate change reversal are overarching goals, we will need to chart the carbon footprint of all phases of the program, with special attention to the long-term operational phase. Just the measuring of the process will consume millions of donor dollars.

We think that scale investment in monitoring is worth it because in coming years as the responses to the climate catastrophe grow increasingly frantic, trillions will be thrown at poorer solutions like BECCS, DACCS, solar radiation management, and ocean remineralization. Some fools may even throw more money down the nuclear rat hole.

Our objectives are low-tech, anti-fragile, and human-centered. By using tools of permaculture design, we place humans within a new context that will regenerate and sustain natural ecosystems. Humans are not a separate ecosystem, they exist within all the other overlapping ones and must meet their own needs with that in mind.

When we consider social goals we have to meticulously measure how those will impact on natural systems and the planet. In the next short while we will be moving from a polluting economic model to capturing more than our own emissions and ecosystem restoration. Any industries that can fit into this new paradigm will be welcome. Any that can’t will become obsolete.

Biochar offers many strategies that function at the gigaton scale to draw legacy carbon from the atmosphere and ocean. Rather than think in terms of one to four gigaton drawdown potential from agricultural applications for biochar, we need to start thinking in terms of 50 to 100 gigaton CO2 removal annually using biochar in all its versatile, socially and ecologically responsible ways. Global human greenhouse gas pollution today is around 40 gigatons annually in CO2-equivalent (although Covid is predicted to bring a 2 Gt reduction). So, we need to start thinking of drawing twice that much down each year, and putting it somewhere productive, not just down a well.

When most governments and think tanks talk of development today, they try to measure it in terms of economic growth, jobs, stock market highs and lows, gross domestic production, electrical generation, or resource extraction. Some of the more far-sighted use metrics like inclusion, intergenerational equity, longevity, and happiness. Yet, just as all politics is local, all economics is local. It comes down to how well any community — be it rural cluster of farms or an urban neighborhood — fends for itself. We are all going to witness this first hand during the economic recovery phase of the Covid crisis. Just as the infection was spotty at first, so the recovery will be one of pop-up successes and failures.

Our plan is to begin with some of the resource-poorest people on the planet — climate and political refugees — and help them to perform ecosystem regeneration. We will encourage and seed forward-thinking, community-based, regenerative microenterprises to meet their needs into the indefinite future.

We want to reverse climate change and build a new prototype for equalitarian, cooperative, human society at the same time. And, we appreciate your help.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. My latest book, The Dark Side of the Ocean, is nearing that moment. Please help if you can.

Comments