H is for Hopium

"My hope derives from a different lived experience. Ecovillages are not imaginary."

One of the Easter eggs in Elizabeth Kolbert’s latest masterwork, H is for Hope, is the uncredited cameo in the audiobook by Christiana Figueres, UN midwife of the Paris Agreement, reading her own quote. There was barely a trace of her Costa Rican accent to give her away — you’d have to know her or have listened to her podcast.

A long-time environmental reporter for The New Yorker, Kolbert won the General Nonfiction Pulitzer Prize for The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History in 2015. I loved her Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature, and Climate Change. I devour everything she writes.

Each of the 26 chapters of the new book begins with a letter of the alphabet. Chapter D is particularly striking. It is just 9 words or 12 seconds in the audiobook.

Despair.

Despair is unproductive.

It is also a sin.

I could compare that to haiku but it does not follow the traditional form. It is more of a koan. One mediates to grasp a deeper meaning but there is not much to grasp. It is just simple and straightforward. In a later chapter (R is for “Republicans”), Kolbert relates that in the summer of 2022, when New York City was suffering a sweltering heat wave, The New York Times asked several thousand residents to name the most important problem facing the nation.

USAnians are not despairing — that would be unproductive — they are ignoring. According to 1 Corinthians 14:38 (“If anyone does not know, he will not be known”), ignorance is also a sin.

Addictive, overindustrialized, consumerist culture will not find some magical technofix to rescue it from climate change. Sustainability should always be questioned by first asking, “What is it you are trying to sustain?”Cutting

emissions to near zero (they’ve steadily increased every year since the

Kyoto Protocol passed in 1997, with only a brief pause in 2021) might

arrest further warming (color me skeptical on that), but weirding

weather, catastrophic sea level rise, and the high rate of natural

calamities would continue.

Electrification of everything, re-sourcing electricity, and tapping gravity, wind, wave, and geothermal will all smooth the transition to a more viable human future, but as Kolbert points out, that won’t mean a transition back to an addictive, over-industrialized, consumerist culture. It will not Make America Great Again. It will be a transition to something vastly different than our biological evolution has prepared us for. There are, she says, unknown unknowns.

We are being dragged into this unknowable future, either kicking and screaming or quietly protesting, but we can’t avoid it. That ship has sailed. The greatest challenge will be altering our behavior to comport with newly discovered realities. The more nimble we become, the better for everyone and all our relations.

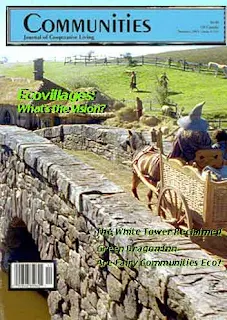

“Changing habits” in its simplest iteration, could be merely to return to the typical lifestyle of homo before smartphones, electricity, and the widespread use of coal and oil. With recently acquired skills and knowledge — of plants, nutrition, regenerative farming, renewable energy, and natural building — it need not be the hard daily grind of some feudalistic earlier age but could be more like The Shire. Meet me at the Inn of the Prancing Pony in Bree on the Great East Road, and we will share some Old Toby pipeweed.

Crafting a Narrative

In her book, N stands for narratives:

“Narratives are socially constructed stories that make sense of events thereby lending direction to human action.” So observes a paper published recently in the journal Climatic Change by a team of European researchers. Climate change narratives, the team notes, typically foreground doom and gloom. Often they emphasize risk. If they are not retailing the latest warming-related disasters — fires, floods, food shortages — they’re predicting a future filled with even grimmer warming-related disasters — bigger fires, more severe flooding, and famines that threaten entire regions. This approach, the researchers argue, can be counterproductive.

Narratives of fear can become self-fulfilling prophecies. If people believe that things will only get worse they feel overwhelmed. If they feel overwhelmed, they’re apt to throw up their hands, thus guaranteeing that things will only get worse. A diet of bad news leads to paralysis which yields yet more bad news. What’s needed instead, the paper goes on, are narratives that empower people to act. Such narratives tell a positive and engaging story. They articulate a vision of where we want to go and outline steps that could be taken to arrive at this metaphorical destination. Positive stories can also become self-fulfilling. People that believe in a brighter future are more likely to put in the effort required to achieve it. When they put in that effort, they make discoveries that hasten progress. [my emphasis] Along the way they build communities that make positive change possible. Particularly compelling by the researchers’ account are win-win narratives. Some win-win narratives demonstrate how people can reduce emissions and, in the process, make money. Others center on more intangible goals such as creating a better world.

Perhaps I love this passage so much because it describes the strategy I latched onto 52 years ago when I chose to join a proto-ecovillage in Tennessee and help make it go, rather than pursue the destiny my parents had in mind when they sent me to grad school. But intentional communities are not simple, or easy. They are utopian visions clad in the hairsuit of opposition to society. Your vision for a better world runs against the cultural current. Never doubt the power of the forces arrayed to bring about your failure.

Assuming the ecovillage/eco-district/ecoregion vision was to attract a larger following, what sort of personal sacrifices might still be entailed? Would you give up your car? Your dog? Your lawn? Where is the balance struck between a happy Shire narrative that would attract the multitudes and the practical necessities of adapting to and mitigating a now-changed and ever-worsening climate?

K is for Kilowatt

Kolbert writes:

Americans don’t have the world’s highest per capita emissions — that dubious honor goes to Kuwaitis and Qataris — but we’re up there. Per capita consumption in Thailand and Argentina runs to around two and a half thousand watts and emissions to around four tons. Ugandans and Ethiopians use 100 watts and emit a tenth of a ton. Somalis consume a mere 30 watts and emit just 90 pounds. This means that an American household of four is responsible for the same emissions as 16 Argentinians, 600 Ugandans, or a Somali village of 1600. These figures rarely feature in conversations about climate change in the U.S.

Studies undertaken with academic rigor at a number of ecovillages over the decades have shown that their ecological footprints are a fraction of the outer societies that surround them. Any random visitor would rank ecovillage residents very high on the happiness index. But consider what residents may be asked to forego:

- 1 USAnian = 16 tCO2/y

- 1 Argentinian = 4 tCO2/y, about the same as an ecovillager.

- 1 European Dog = 0.63 tCO2/y (avg); 1.1 tCO2/y (large) [Yavor 2020], so one ecovillager (or Argentinian) has about the same climate footprint as 4 European dogs.

- 1 Tree = minus 0.024 tCO2/y (US Forest Service). To offset the average European dog (or one ecovillager) you would need to grow 167 new trees that would not have grown otherwise. This helps to explain why so many ecovillages establish their own forests. Alternatively, you could grow bamboo and sequester 1.3 tons of biochar per resident every year. (For reference, paving 23 feet of a blacktop road with biochar instead of asphalt will use 1.3 tons).

- 1 new Chevrolet (operating cost) = 4.6 tCO2/y [EPA].

- 1 Tesla (charging cost) = 0.5 tCO2/y [Calma, 2023].

Many ecovillages have car-sharing co-ops (although e-carts and e-bikes are more the norm). Since a fuel-efficient petrol-powered car has an annual footprint of 1.2 ecovillagers, there is a great incentive to switch to plug-in electrics like Teslas.

“Action is the antidote to despair” — Edward Abbey

- To build the standard single family house in the US (2022) = 51.7 tCO2 [Magwood 2024]. That is the equivalent of owning four dogs for their 13-year lives. If your house lasts you 50 years without major repair, you could retire the carbon footprint of its construction by simply not having a dog you might have otherwise had.

- Natural buildings = less than zero. The typical construction of buildings in ecovillages uses all natural materials, often from the site where the building sits. Any parts made of carbon (wood, hemp, straw, etc.) are successfully sequestered from the carbon cycle for the lifetime of the house and longer if recycled or pyrolyzed at the end of use.

It is easy to see that any US ecovillager living at the standard of living of an average Argentinian, sharing a car with a neighborhood (preferably an EV), having no pets and living in a natural building would have a fraction of the 16-ton impact of a typical USAnian clad head-to-toe in Christmas lights.

Life in ecovillages is also infinitely more enjoyable and it has nothing to do with bragging rights. The most important piece of the Kolbert revelation: “When they put in that effort, they make discoveries that hasten progress.”

Thank you for reading The Great Change. This post is public so feel free to share it.

O is for Objections

Kolbert diligently strives to be her own worst critic. Halfway through the book, she brings in Vaclav Smil for a reality check, noting that “the gap between wishful thinking and reality is vast.”

Smil argues, realistically, that most climate “solutions” presuppose “unreliable assumptions” that existing or non-existent technologies will be deployed at fantastic rates or that humanity’s ever-growing appetite for energy will suddenly be curbed. Smil labels such fantasies the academic equivalent of science fiction.

In a surprising mea culpa, Kolbert writes that “Everything I have written from ‘Despair’ onward is vulnerable to Smilian objections.” She then re-describes several previously described hopeful technologies and lists where their hidden faults lie.

Perhaps the greatest gap is the assumption that people can or will change, never mind in a rapid and orderly way. Somehow it is assumed that we will just give up our creature comforts to save the planet and our own species. We only need to be bashed hard enough to get our attention. Then we will rise to the challenge, or so the standard narrative goes.

In an April Fools Day post, James Hansen, Makiko Sato, and Pushker Kharecha of the Columbia University Climate Science, Awareness and Solutions program published a letter entitled “Hope vs Hopium in the acceleration of global warming.” There is much to like in the paper, including watching usually staid academics take the gloves off and come down hard on their naysaying opponents, but unfortunately, Hansen’s determined plan to irradiate the genes of any surviving generations with megaton nuclear bomb factories disguised as power plants sprinkled by the thousands around the world weakens his credibility. Perhaps that part of the letter was just a hamfisted April Fools Day joke.

The Hope vs Hopium concept, however, is spot on. Hansen says what we are seeing in the atmosphere and ocean at this moment is the first significant change in the global warming rate since 1970.

The Columbia team described how global absorbed solar radiation (ASR) has increased dramatically since 2010, more than 1.4 W/m2, equivalent to a CO2 increase of more than 100 parts per million (ppm). Actual atmospheric CO2 in that same period increased from 387 ppm to 420 ppm. The normal for interglacial earth atmosphere is 220–280 ppm CO2e, so we are way outside historical boundaries. Since more CO2 = hot, we are the proverbial frog in the boiling water.

Hansen et al describe the observed 2023–24 ocean surface warming as a phase change, suggesting that the entire climate system may be undergoing some fundamental shift to a higher temperature state for the planet. What had been equilibrium states during the ice ages and warm interglacials are no longer applicable. We have entered an entirely new domain. They say:

In his gloves-off fury, Hansen takes wild swings at Michael Mann (for refusal to concede that global warming is accelerating), Amory Lovins (for accepting donations from Shell and BP, among others) and “Big Green” environmental organizations (of whom he seems jealous because they are better at fundraising). “Big Green is green mainly as the shade of a dollar bill,” he complains.

What do Hansen and Kolbert have in common? Hope.

In both cases, their hope is tempered by long professional lives lived close to the center of public policy making. They have watched the sausages being made, and they know what the population is being fed. Maybe if people, particularly politicians, could just better understand the scope of the problem, they seem to be saying, the policies would change.

My hope derives from a different lived experience. I have been to The Shire. It’s real.

References

Bocco, Andrea, Martina Gerace, and Susanna Pollini. The Environmental Impact of Sieben Linden Ecovillage. Taylor & Francis, 2019.

Calma, J., Tesla’s carbon footprint is finally coming into focus, and it’s bigger than the company let on in the past, The Verge, 2023.

Carragher, Vincent, and Michael Peters. “Engaging an ecovillage and measuring its ecological footprint.” Local Environment 23.8 (2018): 861–878.

Climate Chat: “Hope vs Hopium,” 31 March 2024.

East, May. “Current thinking on sustainable human habitat: the Findhorn Ecovillage case.” Ecocycles 4.1 (2018): 68–72.

Fletcher, C., et al, Earth at risk: An urgent call to end the age of destruction and forge a just and sustainable future, PNAS Nexus, Volume 3, Issue 4, April 2024, page106, https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae106

Gerace, Martina, and Susanna Pollini. “Sieben Linden ecovillage.” The Environmental Impact of Sieben Linden Ecovillage. Routledge, 2019. 5–25.

Giratalla, Waleed. Assessing the environmental practices and impacts of intentional communities: an ecological footprint comparison of an ecovillage and cohousing community in southwestern British Columbia. Diss. University of British Columbia, 2010.

Hansen, James, Makiko Sato, Pushker Kharecha, Global Warming Acceleration: Hope vs Hopium, 2024.

Hansen J, Sato M, Hearty P et al. Ice melt, sea level rise and superstorms: evidence from paleoclimate data, climate modeling, and modern observations that 2 C global warming could be dangerous. Atmos Chem Phys 16, 3761–812, 2016.

Kolbert, Elizabeth. The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. A&C Black, 2014.

Kolbert, Elizabeth. Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, nature, and climate change. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2015.

Littlemore, Richard. Better than hope: in search of a defence against despair in the face of global climate change. Diss. Royal Roads University (Canada), 2019.

Magwood, C. The carbon footprint of the materials for new homes in the US, social media post, 2024.

Ware. B. The 5 most common regrets of the dying — and what we can learn from them, Stylist, Sep 2019.

The Great Change is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

There is a growing recognition that a viable path forward is towards a new carbon economy, one that goes beyond zero emissions and runs the industrial carbon cycle backwards — taking CO2 from the atmosphere and ocean and burying it in the ground. The triple bottom line of this new economy is antifragility, regeneration, and resilience.

Meanwhile, let’s end these wars. We support peace in the West Bank and Gaza and the efforts by the Center for Constitutional Rights, National Lawyers Guild, Government of South Africa and others to bring an immediate cessation to the war. Global Village Institute’s Peace Thru Permaculture initiative has sponsored the Green Kibbutz network in Israel and the Marda Permaculture Farm in the West Bank for over 30 years and will continue to do so, with your assistance. We aid Ukrainian families seeking refuge in ecovillages and permaculture farms along the Green Road and work to heal collective trauma everywhere through the Pocket Project. Please direct donations to these efforts at ecovillage@thefarm.org. You can read all about it on the Global Village Institute website (GVIx.org). Thank you for your support.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger, Substack and Medium subscriptions are needed and welcomed. For reasons unrevealed to us, Meta, Facebook and Instagram have blocked our accounts. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions can be made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

#RestorationGeneration

I am excited to teach the ecovillage approach to regenerative design. Join me and 15 other global changemakers in April 2024 for this online course.

I will also join a distinguished panel of ecovillage practitioners for a Fireside Chat April 18 from 1–2:30 pm EDT asking:

- What is an ecovillage? What is our personal definition?

- How has the term and form changed over the years?

- Are ecovillages a “solution” to climate change?

- What role can we imagine/hope that ecovillages might play in coming years?

Watch ic.org for details on how to join the free Zoom call.

Comments

Folks like James Hansen, with his push for nuclear power, and George Monbiot, with his push for synthetic food grown with nuclear power, are grasping at straws. They are just trying to think of a way to keep billions from premature death. That ship has sailed (on the River Styx).

The real question that needs tackling is how those millions who do survive the big dieoff can make a living on a Hothouse Earth.