Can trees beat machines?

"Forests are the largest terrestrial carbon sink for the planet, both from the production of tree biomass and soil carbon storage"

Treebeard, some call me.

Pippin: And whose side are you on?

Treebeard: Side? I am on nobody’s side, because nobody is on my side, little Orc.

— Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers

The first ‘World Scientists Warning to Humanity’ dates back to 1992, when more than 1700 scientists, including most living Nobel laureates, called on humankind to halt environmental destruction and make fundamental changes to the relationship with the natural world. On August 31, 2022, these scientists issued another urgent “warning to humanity,” this time about the global impact of tree extinctions.

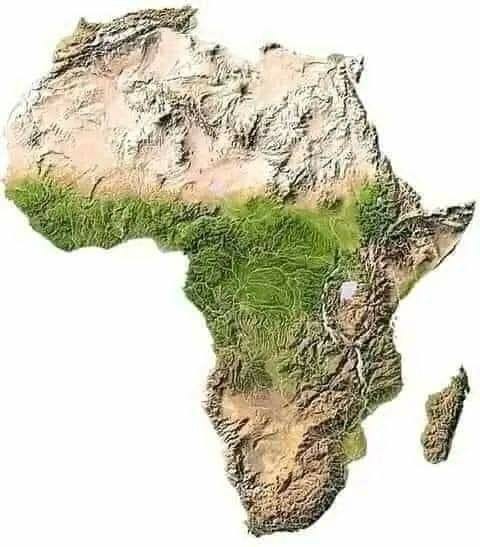

A third of the world’s tree species are currently threatened with extinction. That scale extinction will lead to major biodiversity losses in other species and alter the cycling of carbon, water and nutrients in the world’s ecosystems. Tree extinction will also undermine the livelihoods of the billions of people who depend on trees and their benefits. There are over 15,000 species of trees in the Amazon alone that are threatened, many yet to be named.

Last week I paid a call on an old tree friend I had planted here at The Farm 20 years ago. Ginkgo biloba is the last living species in the order Ginkgoales, over 290 million years old. Lately, Ginkgo is experiencing something of a comeback, thanks to its value in medicine, known to the Chinese since at least the 11th century. Ginkgo seeds, leaves, and nuts are traditionally used as cognitive enhancers and to treat dementia, asthma, bronchitis, and kidney and bladder disorders. I planted two of them but one was too close to our public campground and succumbed to abuse while still a juvenile. The other has now become an esteemed elder of the forest community, even while only 20.

When I explain my natural climate solutions strategy to audiences I often get pushback, particularly from those who think machines will save us and have little appreciation for biophysical economics. The common arguments are:

- Tree planting is all well and good, and forest conservation is even better, but at best it is carbon neutral, once the forests are well established;

- Forested areas produce less food than cleared space and therefore exacerbate world hunger;

- The amount of land required to be planted to remove the gigatons of annual human greenhouse gas emissions, expressed as carbon-dioxide equivalents (40 GtCO2e/y), is well beyond the available land surface area of the planet, and because of sea level rise, that area is shrinking;

- Climate change will threaten any forests you plant — by wildfire, droughts, floods, pests and pathogens; and

- There is no guarantee future people won’t just cut all those forests down to make space for producing food, fuel, timber, and human habitat.

I will try to address each of these points in summary, although any one of them could merit its own essay.

Treebeard: “You must understand, young Hobbit, it takes a long time to say anything in Old Entish. And we never say anything unless it is worth taking a long time to say.”

Tree planting is all well and good… but at best carbon neutral

This canard is the closest to being true. Forests are the largest terrestrial carbon sink for the planet, both from the production of tree biomass and soil carbon storage. Tree biomass carbon storage occurs fastest among juvenile trees and then levels out for old growth, while soil storage is greatest for old growth and less for juvenile trees. Naturally, the deeper the roots of a tree, the farther down carbon exudates are excreted to feed the soil food web, and while some will make their way to the surface and thence to the atmosphere on shorter time scales, more will be deep sequestered for centuries to millennia. In the present climate emergency, timescales matter. The leaf and branch — or dead trunk at end of life — biomass that litter the forest floor, unless converted to recalcitrant carbon molecules (biochar), will return to the atmospheric/oceanic carbon cycle by microbial digestion and excretion or fire. But, established forests are not carbon neutral. They continuously bank deposits of carbon underground. The duration or “permanence” of carbon sequestration can also be enlarged by incorporating more durable wood products and biochar into the built environment and industrial economy.

Forested areas produce less food than cleared space

The Scientists’ Warning says, “All trees can be considered as ecosystem engineers, providing a food resource, shelter, refuge and microclimate for many other species and their associated interactions.” It goes on to say, “Consequently, the loss of trees and the resulting extinction cascades are significant factors in the declines of insect abundance and diversity…” ie: global food supply. Trees are also an important source of essential foods in the form of nutrient-dense fruits, vegetables and nuts. Approximately 53% of the fruit and 100% of the nuts available for consumption globally are produced by trees. Have you been drinking almond or cashew milk lately? As we phase out climate-damaging beef and dairy, expect to see much more of these products on your grocery shelves. Consider also that some forest mushrooms (shiitake) have protein of equal quality to milk, eggs, or meat, with fewer negative health impacts.

The amount of land required to be planted is well beyond the available land surface area … and shrinking

In 2015, Frank Michael and I published a paper called Climate Ecoforestry that looked at the requirements of drawing down either 40 GtCO2e/y or the legacy 2.5 TtCO2e using only forestry. We determined that you would need to plant 200 Mha/yr (equivalent to 4 Spains) to get a net drawdown of 11 GtCO2/y initially and 50 GtCO2/y by year 24. Assuming a reasonable curtailment of man-made emissions over the coming century, we concluded that a pre-industrial atmospheric stasis was recoverable before 2100 solely by tree planting. Is there enough space? Yes. Don’t forget that prior to human influence, forests covered an order of magnitude more land than they do today. Urban forests are all the rage, and for good reason. Silvopasture, agroforestry, conservation easements, and rewilding are all growth practices. They can expand even faster with the appropriate incentives. Our extensive calculations can be downloaded, modeled and vetted to your heart’s delight.

Climate change will threaten any forests you plant…

Yes. It will. This is why forests cannot be viewed as something apart from human ecosystems. Humans will always have a role in planting, cultivating, and regeneratively managing forests.

There is no guarantee future people won’t just cut all those forests down…

The Scientists’ Warning says:

Worldwide, more than 1.6 billion people live within 5 km of a forest, a figure that includes approximately 250 million (40%) of the world’s most extreme poor (Miller et al., 2020; Newton et al., 2020). Many of these people depend on products and services provided by trees to support their livelihoods. The 60 million indigenous people who live in forest areas are especially dependent on trees and the condition of forest ecosystems (SCBD, 2010). Trees can contribute to meeting energy, health, housing, income and nutritional needs, as well as nonmaterial aspects of livelihoods such as community relations, culture and spirituality (Miller et al., 2020). For example, in India, more than a quarter of the population (i.e. 275 million people) are dependent on forest resources for subsistence and income generation (Milne, 2006).

***

Close linkages between human well-being and tree resources also create the possibility of abrupt decline or collapse occurring simultaneously in both social and ecological systems (Barrett et al., 2011). Effective conservation of trees can reduce such risks to human livelihoods and can help people to avoid increased impoverishment. This can be achieved through the role of trees in furnishing food, fodder, fuel and other products when alternatives are not available, providing a form of ‘safety net’ to livelihoods (Marshall et al., 2006). This is especially important to the rural poor because they often do not have access to other forms of insurance, and they often rely on other livelihood activities that are vulnerable to external shocks such as drought (Noack et al., 2019).

Conversely, investment in tree resources through approaches such as forest protection, sustainable use and domestication can provide potential routes out of poverty (Marshall et al., 2006). This can be achieved directly through the sale of tree products and indirectly by enhancing soil fertility, water regulation and the provision of other ecosystem services that support food production and other livelihood requirements (Miller et al., 2020). For example in Mexico and Bolivia, Marshall et al. (2006) showed that nontimber forest products can provide cash income in subsistence communities where families may have no other cash-generating opportunities. Accumulation of cash savings, through the commercialization of tree products, can provide a vital ‘stepping stone’ to a nonpoor life.

Perhaps even more important as we enter an ever-warming Anthropocene is the psychological impact. This summer, drought and a string of heat waves hit Europe, China and the US. This heat in turn caused psychiatric hospitalizations, increased rates of suicide, and domestic violence, according to validating research. Using artificial intelligence to identify about 75 million hate messages on Twitter, scientists analyzed how the number of hate tweets spiked when local temperatures increased. Aggressive behavior online made for violence offline, including mass shootings, lynchings, and ethnic cleansing, according to the Council on Foreign Relations. The reason urban forests are being replanted now is because they have been proven to cool cities. But they also cool tempers.

Human origins trace back to trees. As we descended and stood upright, and cut down forests to build golf courses or attempted to assuage our primal urges to look out over the savannah by putting balconies on high-rise apartments, we lost an essential connection to our own nature. As we return to being forested civilizations — essential now to climate survival — we’ll regain more than atmospheric equilibrium.

We’ll regain our humanity.

Towns, villages and cities in the Ukraine are being bombed every day. As refugees pour out into the countryside, they must rest by day so they can travel by night. Ecovillages and permaculture farms have organized something like an underground railroad to shelter families fleeing the cities, either on a long-term basis or temporarily, as people wait for the best moments to cross the border to a safer place, or to return to their homes if that becomes possible. So far there are 62 sites in Ukraine and 265 around the region. They are calling their project “The Green Road.”

The Green Road also wants to address the ongoing food crisis at the local level by helping people grow their own food, and they are raising money to acquire farm machinery, seed, and to erect greenhouses. The opportunity, however, is larger than that. The majority of the migrants are children. This will be the first experience in ecovillage living for most. They will directly experience its wonders, skills, and safety. They may never want to go back. Those that do will carry the seeds within them of the better world they glimpsed through the eyes of a child.

Those wishing to make a tax-deductible gift can do so through Global Village Institute by going to http://PayPal.me/greenroad2022 or by directing donations to greenroad@thefarm.org.

There is more info on the Global Village Institute website at https://www.gvix.org/greenroad

The COVID-19 pandemic has destroyed lives, livelihoods, and economies. But it has not slowed down climate change, which presents an existential threat to all life, humans included. The warnings could not be stronger: temperatures and fires are breaking records, greenhouse gas levels keep climbing, sea level is rising, and natural disasters are upsizing.

As the world confronts the pandemic and emerges into recovery, there is growing recognition that the recovery must be a pathway to a new carbon economy, one that goes beyond zero emissions and runs the industrial carbon cycle backward — taking CO2 from the atmosphere and ocean, turning it into coal and oil, and burying it in the ground. The triple bottom line of this new economy is antifragility, regeneration, and resilience.Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger or Substack subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

The Great Change is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Comments