A Human Tsunami

"Migration of the displaced as an Anthropocene augury"

One in every 97 people in the world is now displaced, a refugee or migrant. At the same time, across Spain and Italy entire towns have been abandoned for lack of people.

|

Honduran migrants walk to the U.S. through Mexico. |

In 2018 and 2019, Afghanistan experienced its worst drought of the 21st century. It left more than 14 million people food insecure. The war had displaced 3.5 million Afghans from their homes and farms. After the fall of Kabul in 2021, more than half a million Afghans applied for asylum in Europe, adding to the already 2.6 million Afghan refugees around the world. In February 2022, the United States announced it had determined to permanently remove and give to charity the $9.5 billion it had impounded from the Afghan Central Bank in 2021. That crashed the banks, taking the life savings of millions of Afghans, and with the simultaneous suspension of billions in IMF, World Bank, and bilateral assistance, the lifeline of Afghans sheltering abroad and the salaries for hundreds of thousands of security and civil service employees and aid workers abruptly ended. This has led to a severe food and medical crisis, in which 8 million Afghans are now thrown onto the brink of famine and hospitals can no longer afford staff salaries or medical supplies amidst the Covid pandemic. It is a completely man-made crisis, done with the stroke of a pen.

It is expected that as many Afghans as can will leave their country and attempt to cross into Europe. England has determined that the Channel will become its moat, fortified at every port with razor wired walls and guard towers. Its strategy recalls Pharaoh Ramesses II in 1276 BCE. Faced with an onslaught of Palestinian and Syrian “sea people” escaping drought, rather than build tent cities to house them and employ their labor to build more pyramids, the Pharaoh simply trapped and sank their boats and sent his chariots to drive survivors back into the sea. The same tactics were used again by Ramesses III in 1200 BCE, raining flaming arrows on approaching ships then setting archers onto any survivors who made it to shore.

Can you imagine scenes like that in Brighton Beach or Camber Sands? What about South Miami Beach? Malibu? Byron Bay? Consider the size of the human tsunami. At least 100 million people, half of them children, have already fled their homes. Fully half the population of Ukraine — 22 million people — are now displaced. The United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees (UNHCR) is funded entirely by donations. Since it can’t hope to transport, house, feed, medically attend to and gainfully employ that many people, it relies on the generosity of receiving nations, where increasingly the politics is souring on immigration.

By 2030, about 250 million people may experience high water stress in Africa, with up to 700 million people displaced as a result

— IPCC Working Group II, 2022.

During the Syrian War in 2015 and 2016, 1.2 million first-time asylum-seekers arrived in Europe. Sweden took in 156,110, Norway 30,470 and Denmark 20,825. In Sweden, they became 1.6% of the population. In Norway, bicycles piled up at Storskog because Russian rules prohibited border crossings on foot, so refugees crossed on cheap, one-way bikes — 5500 of them left behind there in a rusting pile. Germany received over one million first-time asylum applications.

|

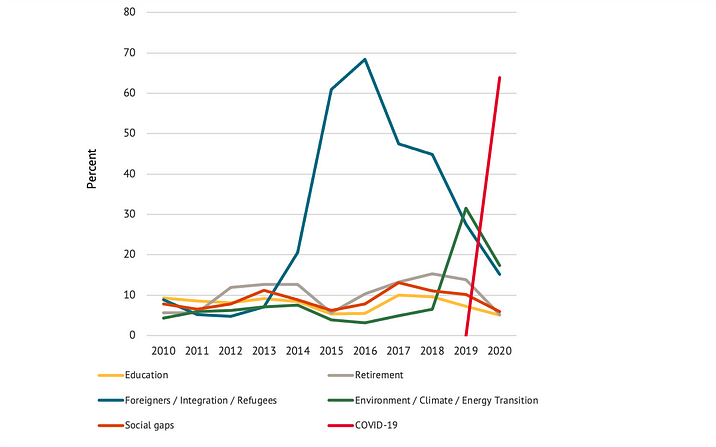

Ranking of most common concerns in Germany 2010–2020, |

In 2021, 190,800 asylum applications were submitted to Germany’s Federal Office for Migration and Refugees. It was the calm before the storm. ClimateRefugees.org reported March 3, 2022:

Climate scientists point to climate change and an ongoing La Niña — a climate pattern resulting in dryer weather for the Horn of Africa — as the cause. Those same climate scientists also predict a 90% chance that the upcoming March, April, May rainy season in the Horn of Africa will be depressed resulting in a fourth consecutive failed rainy season for Somalia. With this information, the International Organization for Migration’s (IOM) Displacement Tracking Matrix analysis projects the current drought will go on to displace between 1,036,000 to 1,415,000 over the next six months.

Syrians in the Nordics

By 2015, the Syrian crisis had led thousands to attempt to cross the Mediterranean in ramshackle vessels. Many drowned. Some ended up in Greek or Italian detention centers or camped at Eastern European borders. Some managed to reach countries further north that were more accepting. The visual images displayed on print media and television were striking and heartbreaking. It led many in Europe to debate the need for compassion over concerns for economic stability and security. In the end the northernmost nations chose to invest in the migrants.

Prior to 2015, Sweden had taken a comparatively liberal approach to immigration and prized cultural diversity. Newcomers were given equal social rights to citizens. But the 2015 refugee crisis so overwhelmed Sweden that the immigration issue became politicized.

Sweden, Norway and Denmark, although accepting more than their share of the burden, tried to avoid appearing attractive to migrants and entered the European “race to the bottom,” with more restrictions on access to social services, education, work, and health care. While holding its foot above the brake, Sweden provided municipalities extra funds for housing projects and food aid. All municipalities were required to settle a certain number of the newcomers and coordinate their language and orientation programs. New regulations entitled migrants to permanent residency if they succeeded in obtaining work or otherwise became self-sufficient.Denmark, long hawkish on immigration, clenched up even more. It cut migrants’ integration allowance. It passed a so-called “jewelry regulation, ” allowing police to confiscate refugees’ valuables without sentimental value exceeding €1340, in order to let them know they were expected to support themselves from work, not from sale of their heirlooms.

Seven hundred million people. For context the entire population of Africa is 1.4 billion. That means by 2030 half the continent of Africa could be displaced as a result of climate change.

— Mark Raulerson, Climate Refugees

Partly as a result of these reluctant resettlements, within five years the Swedish and Norwegian economies were booming. They were doing much better than countries with more restrictive immigration policies. They had wiped away the problem of an aging demographic and filled the ranks of the working class with energetic innovators who would pay into their welfare systems. In 2020–21, Sweden minted six new unicorns (private startups worth more than US$1 billion).

Instead of border forces, immigration control, and detention camps, the northern countries invested in migrant families to help them integrate smoothly into their new homes. They offered more than housing and work. They gave them language classes, buddy systems, health care, and child care. Not surprisingly, the impacts were hugely positive. The choice of compassion provided both economic stability and security.

Motivating Factors

Because of the fertility decline, Europe is estimated to soon be losing about 1.4 million working age people per year. 1.4 million per year is higher than the highest influx from Syria during the crisis. Arguably, they need those refugees in Europe. But Europeans are also looking over the horizon.

Beyond personal security and freedom from autocratic management, population density creates stresses to land, water, food supply, and ecosystem health. Climate change then becomes a force multiplier. And let’s be honest, it is not additive, it is multiplicative. The IPCC Special Report on Climate Change and Land warned:

In some situations, exceeding the limits of adaptation can trigger escalating losses or result in undesirable transformational changes such as forced migration, conflicts or poverty. Examples of climate change induced land degradation that may exceed limits to adaptation include coastal erosion exacerbated by sea level rise where land disappears, thawing of permafrost affecting infrastructure and livelihoods, and extreme soil erosion causing loss of productive capacity.

The agency also said that areas with rapidly growing populations are at much higher risk than regions where populations are smaller and stable, something we are now seeing playing out from Central America to Eurasia and Northern Africa.

- UNHCR says there are over 4.1 million Iraqis in need of humanitarian assistance.

- The Bangladeshi government relocated Rohingya refugees to an island in the Bay of Bengal.

- About 4.6 million Venezuelans have become migrants as a result of shortages of food and medicine and lack of security.

- Unprecedented drought has created 2.3 million South Sudanese refugees, 80% women and children.

- The Democratic Republic of Congo is hosting over 500,000 refugees from nearby countries including Burundi, the Central African Republic and South Sudan. At the same time, it is estimated that 5 million people in DRC are internally displaced, and over 918,000 have fled to neighboring countries like Angola, Rwanda, Tanzania and Zambia.

- In November 2020, when armed conflict broke out in the northern region of Ethiopia known as Tigray, about 60,000 people fled to nearby Sudan but some 2 million are internally displaced and 4.5 million need assistance. The UNHCR reports that more than 3,000 people are leaving Tigray for Sudan every day.

- In the central Sahel, which includes Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso, an estimated 13.4 million people, of which five million are children, are in need of assistance. Refugee outmigration has begun affecting neighboring Chad and Mauritania and coastal countries Benin, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire and Togo.

- At the end of 2021, more than 200,000 people in Central African Republic became displaced in less than two months.

- Somalia sent 750,000 refugees to Kenya, Yemen and Ethiopia but more than 2.6 million people are still internally displaced.

- The Burundi refugee crisis is the least funded in the world, with refugee camps in Tanzania, Rwanda, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo overflowing since 2015.

- On top of all that, in the space of less than one month, more than half the population of Ukraine — 22 million — became displaced from their homes or in severe need.

Despite all of the above, Yemen is likely the worst humanitarian crisis in the world. More than 24 million people are in need. 3.6 million have become internally displaced. Almost two-thirds of the population is on the brink of famine.

If this seems like an onrushing tsunami, consider that last year China posted the lowest fertility rate it’s ever seen — 1.3 children per woman. That portends a crash in the population of China by about 730 million. China alone could absorb the present refugee crisis.

All of sub-Saharan Africa is responsible for less than two per cent of the carbon emissions currently heating the earth; the United States is responsible for twenty-five per cent.

— Bill McKibben, In a World on Fire

One in every 97 people in the world is now displaced. That number will grow. At the same time, fertility rates around the world are crashing very quickly. Many economists are warning that the overdeveloped world is in a population crisis of its own, about to default on promises of pensions and security for the elderly because of a shrinking working class to pay for them.

The time it took for the UK to reduce from 6 children per woman to 4.5 was 80 years. Rwanda recently did that in about five years. Iran dropped from about 4.5 to 2.1 in about 11 years. There is a reason we’re seeing a rapid acceleration in the declines in fertility. Global literacy increased from 40 to 80 percent between the 1960s and 2015. Women were the largest part of that. They took more control over their family planning.

Washing machines and kitchen appliances also mattered. Thanks in large part to distributed solar panels, some 650 million people in India got access to electricity for one sixth of the entire CO2 emissions footprint of the UK. That access to electricity between 1981 and 2011 translated directly into more girls becoming literate, which meant fewer children per woman in the next generation, and fewer still in the generation after that. That change came at a carbon cost of about one third of a ton CO2/year/person, which is not nothing, but it replaced oil and coal which were far worse and India gained a solar manufacturing and installation industry.

Some of the cultural issues swirling around migration may not be the same issues in the future as we saw in the past. We’ve been migrating at different parts of our history so consistently that migration is almost part of the definition of humans. Today it’s been politicized and weaponized and we’re very territorial and it’s all wrapped up in our national identities and things like that; tribal jealousy.

South Korea is demolishing schools because they have no children to teach. Germany is demolishing whole neighborhoods. In remote rural areas across Spain and Italy entire towns have been abandoned.Mekondjo Zefelino, who, despite having a disability, crawled for 106 miles alone to reach Namibia in search of food.

— Mark Raulerson, Climate Refugees

Shall we watch the slow death of communities in wealthy countries, or would we rather be doing the right thing for migrants? Now that we’re moving out of the Holocene period, we don’t really know what the carrying capacity of Earth is for our kind. We know it will be less than it was. It will matter more how much each of us consumes than how many of us there are. There are graceful paths for that descent and there are brutal ones. Which we choose will dictate the kind of world we’ll create for our children and all who come after. “Kind” is the operative word in that sentence.

References:

Al Jazeera, Poland begins work on $400m Belarus border wall against refugees (Jan 22, 2022)

Behrens, P. “Population, Consumption & Climate Change,” Nick Breeze ClimateGenn (Feb 7, 2022)

Hagelund, A., After the refugee crisis: public discourse and policy change in Denmark, Norway and Sweden, Comparative Migration Studies 8:13 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0169-8

Keita, S. and H. Dempster, Five Years Later, One Million Refugees Are Thriving in Germany, Center for Global Development (December 4, 2020)

Lee, R. A Humanitarian Emergency: The Collapse of Afghanistan’s Banking System, Center for Strategic and International Studies (Dec 17, 2021)

Taylor, D., Two-thirds of UK asylum seekers on small boats had hypothermia or injuries, The Guardian (Feb 14, 2022)

World Vision, The most urgent refugee crises around the world (Mar 06, 2021)

Zivardar, E., I have experienced Australia’s detention policy first-hand — it’s time to end it, The Guardian (Mon 14 Feb 2022)

The Green Road

Towns, villages and cities in the Ukraine are being bombed every day. As refugees pour out into the countryside, they must rest by day so they can travel by night. Ecovillages and permaculture farms have organized something like an underground railroad to shelter families fleeing the cities, either on a long-term basis or temporarily, as people wait for the best moments to cross the border to a safer place, or to return to their homes if that becomes possible. So far there are 66 sites in Ukraine and 265 around the region. They are calling their project “The Green Road.”

The Green Road also wants to address the ongoing food crisis at the local level by helping people grow their own food, and they are raising money to acquire farm machinery, seed, and to erect greenhouses.

Those wishing to make a tax-deductible gift can do so through Global Village Institute by going to http://PayPal.me/greenroad2022 or by directing donations to greenroad@thefarm.org.

There is more info on the Global Village Institute website at https://www.gvix.org/greenroad

The COVID-19 pandemic has destroyed lives, livelihoods, and economies. But it has not slowed down climate change, which presents an existential threat to all life, humans included. The warnings could not be stronger: temperatures and fires are breaking records, greenhouse gas levels keep climbing, sea level is rising, and natural disasters are upsizing.

As the world confronts the pandemic and emerges into recovery, there is growing recognition that the recovery must be a pathway to a new carbon economy, one that goes beyond zero emissions and runs the industrial carbon cycle backwards — taking CO2 from the atmosphere and ocean, turning it into coal and oil, and burying it in the ground. The triple bottom line of this new economy is antifragility, regeneration, and resilience.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger or Substack subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

#RestorationGeneration #ReGeneration

“There are the good tipping points, the tipping points in public consciousness when it comes to addressing this crisis, and I think we are very close to that.”

— Climate Scientist Michael Mann, January 13, 2021.

Want to help make a difference while you shop in the Amazon app, at no extra cost to you? Simply follow the instructions below to select “Global Village Institute” as your charity and activate AmazonSmile in the app. They’ll donate a portion of your eligible purchases to us.

How it works:

1. Open the Amazon app on your phone

2. Select the main menu (=) & tap on “AmazonSmile” within Programs & Features

3. Select “Global Village Institute” as your charity

4. Follow the on-screen instructions to activate AmazonSmile in the mobile app

Comments

You noted that "we don’t really know what the carrying capacity of Earth is for our kind", but we do know enough that it is only a fraction of 7.8 billion. And even with the rapid declines in fertility you described, there is no chance that the 7.8 billion will be reduced to carrying capacity without billions of premature deaths. Cruel as it sounds, the best thing that could happen for the trillions of people yet to be born during the lifetime of our species is that those premature deaths happen as soon as possible, before the climate is utterly ruined.

Indeed, the best thing that could happen is that all the affluent people in modern countries die prematurely, well before the poor migrants who have done virtually nothing to ruin the earth. Unfortunately, those affluent moderns are not likely to agree. Even those of us who are perfectly aware of the best course of action are subject to a form of Augustinian hesitation, "Oh, Master, make me poor and frugal - but not yet!"

But even if we can't get comparatively rich people to die before their time, there is no good reason to turn poor people into more rich people. At this stage of the anthropocene, that type of kindness is misplaced. Rich countries should continue reducing their populations as fast as possible and just suffer the consequences of a lack of workers on their economies and go without the wonderful benefits of living in a multicultural society. Welcoming migrants is good for the migrants and good for the people accepting them, but we dare not do it.

We can help poor people in 'developing' nations make better lives for themselves through family planning and knowledge transfer, if there are things they don't already know about sustainable living (information about ecological horticulture, perhaps), and by sending them food that would otherwise go to animals, but that's about it.