The Great Pause Week 82: Cars that Solve for Climate

"We may see a largely carbon-free road transportation system by 2030."

There were omens in the 1880s that rough times lay ahead for buggywhip makers and blacksmiths. The smart money was backing future unicorns like Gustave Trouvé, Gottlieb Daimler, Armand Peugeot, and Karl Benz.

In

1896, Benz designed and patented his boxermotor for the Motorwagen.

Three years later, Benz was the largest car company in the world. Nimble

wagon- and coach-makers like Studebaker switched horses midstream and

started building kerosene cars and electrics, hoping to catch Benz. The

carmakers’ downstream ecosystem, from harness-makers to oats and manure

haulers, never saw it coming.

|

Benz Patent Motorwagen 1885 |

Of the

13,000 carriage makers operating in the U.S. in 1890, only a handful

were still in business by 1920. Model T’s delivered 4x the speed, 10x

the distance per day, with the cargo capacity of four horses at one

tenth the cost of one. By 1913, assembly line innovations from Ransom

Olds and Henry Ford had taken the costs of cars below the breakeven

point for the carriage. An entire 6000-year-old industry was put out to

pasture. The 93 million acres in the US used to produce feed for horses

and mules shrank to just 5 million in 20 years.

“Humankind has traveled for centuries in conveyances pulled by beasts, why would any reasonable person assume the future holds anything different?”

— Carriage Monthly, 1904

As I was delving into the precision fermentation issue a few weeks ago, I had my mind changed about something besides cows: self-driving cars. I have been reading the stories of autonomous Teslas attacking emergency vehicles. Would you really trust one of those at a school crosswalk?

|

Daimler Lastwagen 1896 |

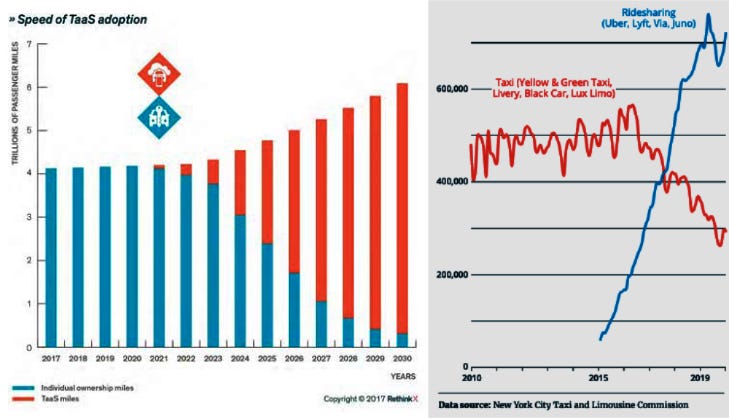

In May 2017, RethinkX published a Seba Technology Sector Disruption Report, Rethinking Transportation 2020–2030. Some key findings:

- Within 10 years of regulatory approval of autonomous vehicles (AVs), 95% of U.S. passenger miles traveled will be served by on-demand autonomous electric vehicles owned by fleets, not individuals.

- The average American family will save more than $5,600 per year in transportation costs, equivalent to a wage raise of 10%. This will keep an additional $1 trillion per year in Americans’ pockets by 2030, potentially generating the largest infusion of consumer spending in history.

- Uber, Lyft and Didi are already engaged, and others will join this high-speed race. Winners-take-all dynamics will force them to make large upfront investments to provide best in class software and the highest possible level of service.

- Million-mile vehicle lifetimes (drivetrains are already there), and far lower maintenance, energy, finance and insurance costs. Far fewer cars will be needed in the U.S. vehicle fleet, and therefore there will be no supply constraints to building out rapidly.

- Transport-as-a-service

will be four to ten times cheaper per mile than buying a new car and

two to four times cheaper than operating an existing vehicle in five

years. It will be similar for the cargo fleet.

…the same processes and dynamics that drive S-curve adoption of new products at a sector level repeat at the level of civilizations.

— James Arbib, Introduction to Rethinking Humanity

- By 2030, individually owned internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles will still represent 40% of the vehicles in the U.S. vehicle fleet, but they will provide just 5% of passenger miles, contributing to cleaner, safer and more walkable communities.

- Many municipalities will see free transportation as a means to improve citizens’ access to jobs, shopping, entertainment, education, health and other services within their communities.

- Productivity gains as a result of reclaimed driving hours will boost GDP by an additional $1 trillion. As fewer cars travel more miles, the number of passenger vehicles on American roads will drop from 247 million to 44 million, opening up vast tracts of land for other, more productive uses.

- Demand for new vehicles will plummet: 70% fewer passenger cars and trucks will be manufactured each year. This could result in total disruption of the car value chain, with car dealers, maintenance and insurance companies suffering almost complete destruction.

- Oil demand will peak at 100 million barrels per day by 2020, dropping to 70 million barrels per day by 2030. This will have a catastrophic effect on the oil industry through price collapse (an equilibrium cost of $25.4 per barrel).

- Approximately 70% of the potential 2030 production of Bakken shale oil would be stranded. So too offshore sites in the United Kingdom, Norway and Nigeria; Venezuelan heavy-crude fields; the Canadian tar sands; and infrastructure such as the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines.

- Assuming a concurrent disruption of the electricity infrastructure by solar and wind, we may see a largely carbon-free road transportation system by 2030.

- While the geopolitical importance of oil will vastly diminish, the importance of lithium, cobalt, neodymium and other elements will rise.

|

Adoption Rates: Autonomous Vehicles; Ride Share |

Already some of Seba’s estimates are proving overly conservative. Four years ago RethinkX estimated electrics would be 60% of the vehicles in the U.S. vehicle fleet by 2030. In Norway, electrics are already 72% of cars on the road and it is only 2021. Ford has announced that all the cars and trucks they will sell in Europe in 2030 will be electric. GM has said it will produce only EVs by 2035.

Blinded by the Light

Of course all this depends on regulatory approval and customer adoption. My question — would you really trust one of those at the school crosswalk? — turns out to be the swinging hinge on the whole proposition of autonomous vehicles. Tesla claims that their cars with autopilot engaged were between six and nine times safer than the average human-driven car in 2020. That was before ‘Full Self Driving’ (FSD) Teslas started kamakazi-ing into police cars, fire trucks and ambulances (17 injuries and one death in 12 crashes to date). It may be that segregation will have to come first — separate lanes, separate highways, separate safety rules for AVs.

— Steve Ballmer, CEO of Microsoft, April 2007“There’s no chance that the iPhone is going to get any significant market share. No chance.”

There is really no need to look back a century for disruptive change. Many of us alive today witnessed what happened to newspaper publishing when Google created AdWords in 2000 or how the music industry counted success in album or CD units sold until Spotify came along and showed that the number of plays per song was where the money was. AirBnB hit hotels. Uber devastated the taxi. Smartphones killed Garmin, Eastman Kodak, the Walkman, and some would say democracy. An EV doesn’t just take kids to soccer practice, it can power your house for a few days in an emergency (or a few weeks if you live in India).

Sales of internal combustion engine vehicles peaked in 2019 and were declining but fortunes suddenly changed in late 2021 when VW, Honda, Ford, GM, and Toyota halted assembly lines due to semiconductor chip shortages. Resale values on used vehicles were at zero or below in many regions and used car dealerships had been closing until they were rescued by climate change. The worst drought in over 50 years struck Asia and a lack of monsoon rains forced Taiwanese chipmakers — 63 percent of the global market — to ration water. It didn’t just stall car production, it stalled new products from Apple, Samsung and Xbox. These lapses and rescues are short-lived however, because the revolution will not be denied.Tony Seba says disruptors tend to come from outside an existing industry because “Incumbent mindsets, incentives, practices, and business models blind existing businesses to the new reality. They double down on the old model rather than create the new.”

Paul Hawken’s new blockbuster, Regeneration: Ending the Climate Crisis in One Generation, ranks climate solutions in much the way his earlier bestseller, Drawdown, did. “EVs and Mobility” come in second in 2030 with 38 billion tons of CO2 avoided or removed (behind “Tropical Forest Restoration”’s 40 GtCO2) but slips into number one with 122 Gt by 2040 and soars ahead of the pack with 226 billion-ton drawdown potential by 2050. When you consider that all man-made emissions summed are now approximately 40 GtCO2 per year (and still rising), this means that a significant part of those could be avoided or withdrawn by transportation changes alone, just in this decade — and 5 times that by 2050.

The new system can be fundamentally different to the old in terms of the structure of the value chain, how value is delivered (business model), the metrics and incentives that drive consumers (demand), producers and investors (supply), and policymakers (regulation).***As we enter the most disruptive decade in human history, with every sector of the economy on the cusp of disruption, this failure matters. Whether we are planning investments, education, social and environmental policy, or infrastructure spending, narrow linear mindsets blind us to the emerging possibilities and the pace and scale of change approaching — society is hurtling towards the future with a blindfold on.

— Tony Seba

These kinds of smart tech transformations — in communications, food, energy, and transportation — are changing everything, rapidly, including, maybe even, the climate.

Insha’Allah إِنْ شَاءَ ٱللَّٰهُ,

__________________________

The COVID-19 pandemic has destroyed lives, livelihoods, and economies. But it has not slowed down climate change, which presents an existential threat to all life, humans included. The warnings could not be stronger: temperatures and fires are breaking records, greenhouse gas levels keep climbing, sea level is rising, and natural disasters are upsizing.

As the world confronts the pandemic and emerges into recovery, there is growing recognition that the recovery must be a pathway to a new carbon economy, one that goes beyond zero emissions and runs the industrial carbon cycle backwards — taking CO2 from the atmosphere and ocean, turning it into coal and oil, and burying it in the ground. The triple bottom line of this new economy is antifragility, regeneration, and resilience.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

#GenerationRestoration

“There

are the good tipping points, the tipping points in public consciousness

when it comes to addressing this crisis, and I think we are very close

to that.”

— Climate Scientist Michael Mann, January 13, 2021.

Want to help make a difference while you shop in the Amazon app, at no extra cost to you? Simply follow the instructions below to select “Global Village Institute” as your charity and activate AmazonSmile in the app. They’ll donate a portion of your eligible purchases to us.

How it works:

1. Open the Amazon app on your phone

2. Select the main menu (=) & tap on “AmazonSmile” within Programs & Features

3. Select “Global Village Institute” as your charity

4. Follow the on-screen instructions to activate AmazonSmile in the mobile app

Comments

I didn't read anywhere their taking account of the ecological consequences or even potential to rewire society as fast as they predict, not the monetary consequences of extreme debt/assets or even debt to GDP global. All set to hang up: global BLUE SCREEN.

Maybe it's time for the fourth revision of your collapseniks chart from 2014; there are quite a few new players like Seba on the scene now. Have you moved from lower left quadrant, technoskeptic doomer along with such worthies as Greer, Eisenstein, Foss, Heinberg, Orlov, Bardi, Lovelock, Odum and Tainter?