The Great Pause Week 79: Building Mouse Utopias

In September, 2020, a rodent named Magawa won the animal equivalent of Britain’s highest civilian honor for bravery because of his uncanny knack for uncovering landmines and unexploded ordnance. In 2016, he travelled from his home in Africa to Cambodia’s famed Angkor temples to begin his bomb-sniffing career. Trained to cover the area of a tennis court in 20 minutes, he detected and alerted his handlers to 71 landmines and 38 items of unexploded ordnance in his four year career. While Magawa may have saved countless people from death or maiming, scores of his fellow migrants may have saved even more. They were trained to sniff out asymptomatic tuberculosis patients.

Winning gold metals was better than discovering utopia for these rodents. That’s because utopia may not be all it is cracked up to be. Working with National Institute of Mental Health from 1954 to 1972, the American ethologist and behavioral researcher John B. Calhoun created what he considered the perfect mouse utopia — unlimited food and water, multiple levels, and private nesting areas.

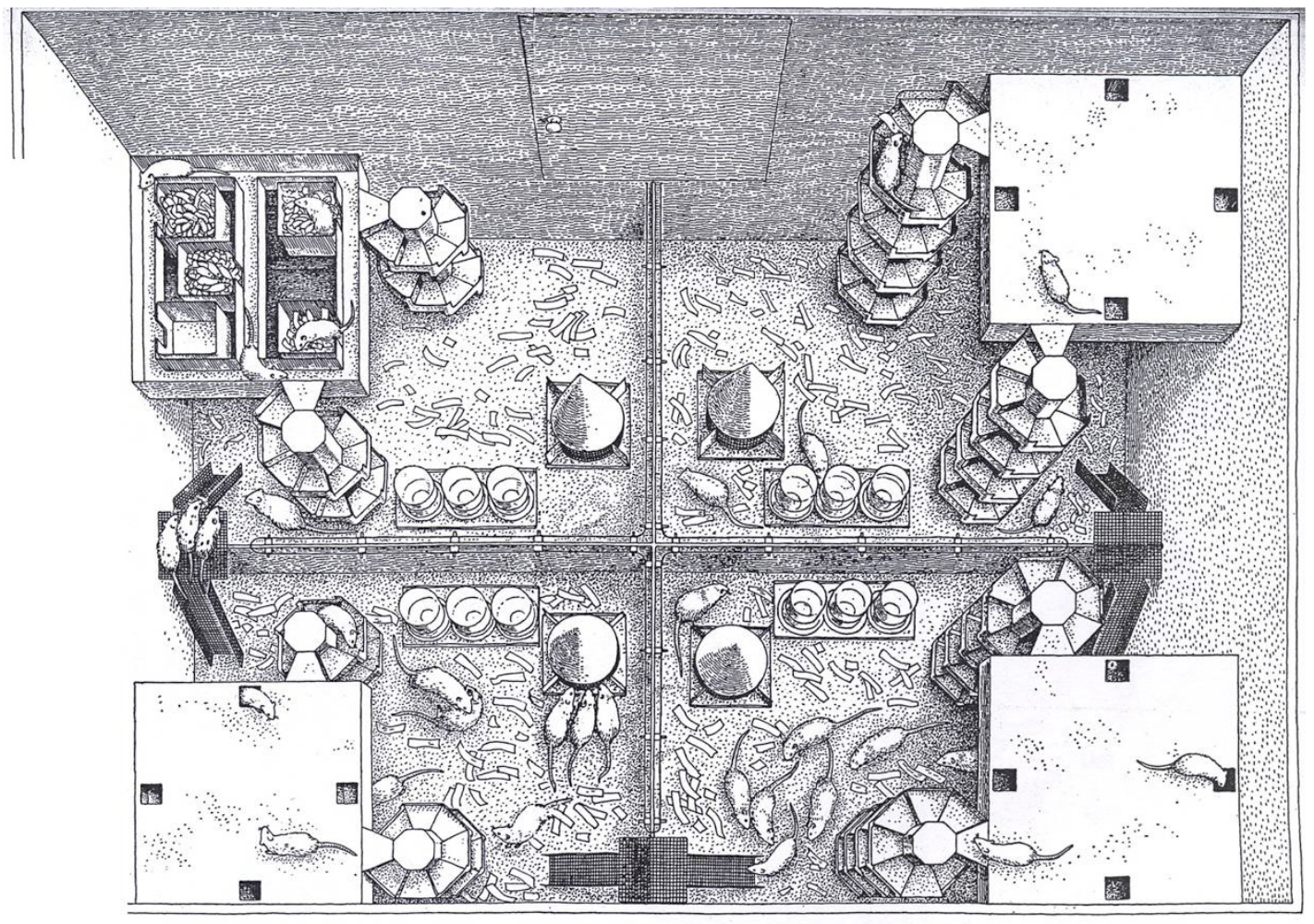

He repeated his experiment 25 times at different scales and observed nearly identical results every time. The layout was a rectangle measuring ten feet by fourteen feet divided into four equal sections equipped identically with a food hopper, water and nesting areas and separated from section to section by electric barriers.

|

| Universe 25 |

His final experiment, “Universe 25,” had space for 3,840 mice but population peaked at 2,200 and began to decline from there because the mice were exhibiting a what Calhoun called a behavioral sink — an increase in pathological activities due to the stress involved in high density living.

Regardless of the scale of the experiments, the same set of events would transpire each time:

- The mice would mate and breed in large quantities.

- Eventually a leveling-off would occur.

- The rodents would develop either hostile or anti-social behaviors.

- The population would trail off to extinction.

Males would lash out at other members — including infants — often biting and wounding them. Females would stop nest building or caring for the young. Eventually infant mortality topped 90 percent, mainly from abandonment.

The death phase of each experiment consisted of two stages: the “first death” — characterized by the loss of purpose in life beyond mere existence (including the loss of desire to mate, raise young, or establish a role within society) — and “second death” marked by the literal end of life and the extinction of the colony. But, ominously, it did not end there.

Before the death of the colony, Calhoun took the four healthiest males and females and allowed them to breed. Placed in a fresh new environment without all of the stress, one might expect a new generation of mice to follow. What Calhoun saw instead was epigenetic damage. Mouse behavior had been so inexorably abused that none of the infants survived to reproduce. Calhoun said, “I shall largely speak of mice, but my thoughts are on man, on healing, on life and its evolution.”

More than six decades have passed since Calhoun conducted his last experiment, nonetheless, questions linger.

Sure, we can be heartened by the fact that humans are not mice. We have science, technology and medicine to heal ourselves and explore new environments and possibilities. But we should also acknowledge that such distinctions are the standard go-to of incorrigible optimists.

Dennis Meadows, co-author of the original Limits to Growth study in 1971, says the problem is transitioning from rapid forward movement to being quiescent.

It’s like riding a bicycle. It is relatively easy to ride a bicycle and its also relatively easy to stand next to your bicycle holding it there still. But to get from rapid forward movement to dismounting and standing — that is a skill set, which if you don’t master it can cause a lot of damage. And that is what we face in our society. We don’t know, certainly at the community or the national level, how to envision a future that is attractive and which doesn’t have growth in it.

Meadows says population is now clearly declining in a number of nations — China, Japan, Russia, “so rather than fight it, by offering subsidies or banning birth control, it would be useful for governments to try to understand how they can run a system in which the population isn’t continuously expanding.”

In which you don’t continuously need more building stock, in which tax revenues don’t keep going up and up and up, in which there is not a steady supply of young people to support the old people in their pensions and so forth. It’s a lot of interesting problems, which you could address, and which would be intellectually challenging. Until we have answers to those questions we are going to ignore the fact that we are overpopulated.

In 1948, at the International Congress on Population and World Resources, demographer P.K. Welpton challenged the Congress to consider the obvious.

It seems to me that even in countries like the U.S.A., the population is above the economic optimum; that is, we have more people even there than is most desirable from the standpoint of the natural resources which we possess. That does not mean that a rapid decrease in population would be desirable, but I think it does mean that if we could choose between a stationary population of say, 100,000,000 and 150,000,000 or 200,000,000 we should without question be better off with the former.

The United States population today has grown above 330,000,000. It finds itself confounded by multiple interlocking crises — persistent drought in the West, urban decay in the Northeast, and rising sea level along its Atlantic and Gulf coasts. Population should be set not by good times, it is learning, but by what it can feed and shelter in the worst of times.

We have rodents who have mirrored our highest attributes of altruism by sniffing out land mines or tuberculosis, but are still unable to control their own fecundity. The question is, does this separate them from us, or make us more alike?

__________________

The COVID-19 pandemic has destroyed lives, livelihoods, and economies. But it has not slowed down climate change, which presents an existential threat to all life, humans included. The warnings could not be stronger: temperatures and fires are breaking records, greenhouse gas levels keep climbing, sea level is rising, and natural disasters are upsizing.As the world confronts the pandemic and emerges into recovery, there is growing recognition that the recovery must be a pathway to a new carbon economy, one that goes beyond zero emissions and runs the industrial carbon cycle backwards — taking CO2 from the atmosphere and ocean, turning it into coal and oil, and burying it in the ground. The triple bottom line of this new economy is antifragility, regeneration, and resilience.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

#RestorationGeneration

“There are the good tipping points, the tipping points in public consciousness when it comes to addressing this crisis, and I think we are very close to that.”

— Climate Scientist Michael Mann, January 13, 2021.

Want to help make a difference while you shop in the Amazon app, at no extra cost to you? Simply follow the instructions below to select “Global Village Institute” as your charity and activate AmazonSmile in the app. They’ll donate a portion of your eligible purchases to us.

How it works:

1. Open the Amazon app on your phone

2. Select the main menu (=) & tap on “AmazonSmile” within Programs & Features

3. Select “Global Village Institute” as your charity

4. Follow the on-screen instructions to activate AmazonSmile in the mobile app

Comments

Sure does offer explanatory hypothesis for human's tragic tendency to act against our own self-interest.

Is there a sequel? Or only always extinction of the colony survivors?

One of many analogs is modern day use of propaganda by the oligarchic elites of government and corporations et al. When most of us drink the koolaid, the rest of us become the hunted.

[see Mark C Miller Prof in media studies, well published, on propaganda campaign of covid https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YggAXyG7vMw)