The Great Pause Week 59: Joys of Soy

"Demand for soy in the EU uses 6 million square miles. 5.2 million of that is in South America."

Fifty-eight weeks ago I crossed the border from Belize and decided to make my stand in a small Mexican village with dirt streets and thatched roofs. I had been coming here to write for more than ten years and I knew that it would likely be well-insulated from the rest of the world as the pandemic raged. That was true for many months because this town, and many neighboring towns, wisely ignored the denialism of Mexican state and federal health authorities and closed themselves to routine comings and goings. Unfortunately, like many places, willpower faltered, they reopened too soon, many of my neighbors became sick and died, and that continues today. Lacking vaccines, México, like India and Brazil, is an incubator and exporter of Covid variants to the rest of the world. One factor I did not anticipate when I made my decision to remain here was the speed with which effective vaccines would be developed, meaning that the pandemic will be years shorter in the affluent North, where the world’s supplies of vaccine are restarting normality, than in the South, where the pandemic has no end in sight.

A little while ago, I got a hankering for something that is standard fare in my ecovillage in Tennessee but can’t be found even in gourmet vegan restaurants here — boiled soybeans. It is not surprising really, because unless you have been exposed to the rich, buttery flavor of properly cooked beans, you probably accept the myth that they are cattle-feed or something that can only be processed into secondary products like milk, tofu, miso, natto, or tempeh. But all through the 1970s, soybeans were the basis of our diet at The Farm community, not only because they were so versatile, but because they were so cheap. The world price of soybeans at this writing is $14.33 per bushel. In 1972 they were around $5. Adjusting for inflation, that would be $32 today. Today’s soybeans are less than half the price they were in the 70s. The reasons for that are that we grow so many more today than we did in 1972, it is mostly automated —air-conditioned giant combines steered by GPS across flattened fields — and we subsidize the production cost with Saudi oil and fracked gas.

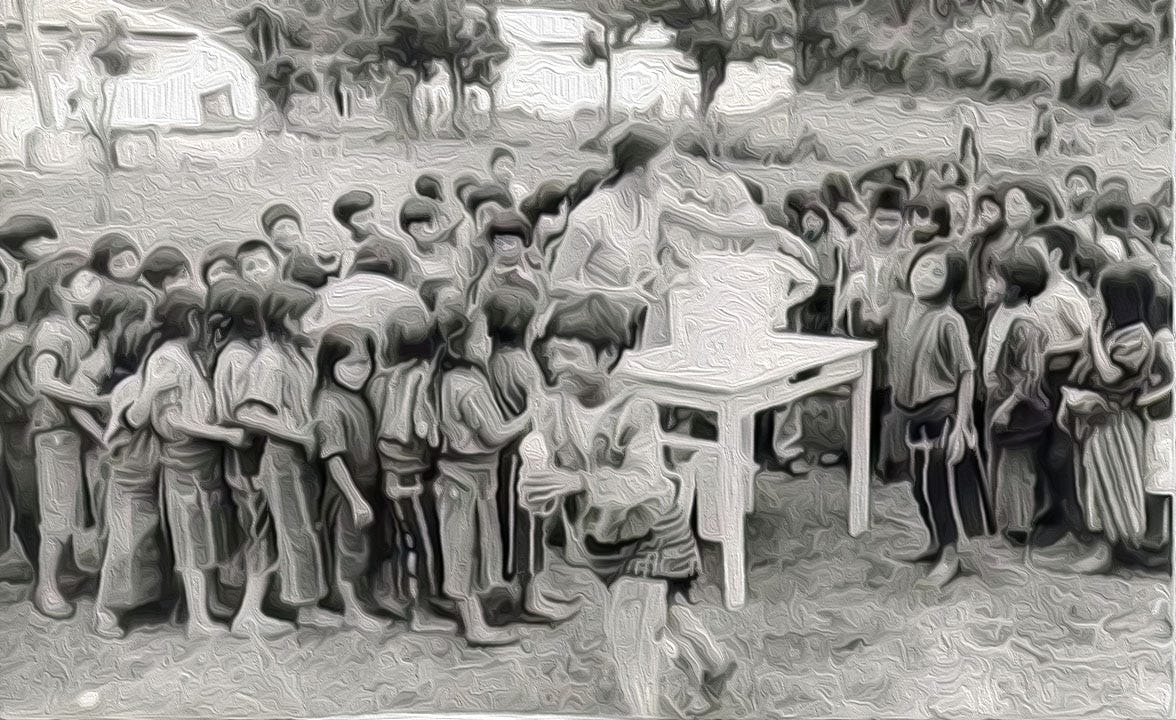

At the Sixth International Permaculture Convergence in Perth, Bill Mollison and I got into a spat in our stage presentations over the question of soy. He called them baby killers. He disliked soy only slightly less than he disliked “land lice,” as he liked to call goats. I showed slides of healthy babies in Guatemala where our project decimated infant mortality by introducing non-GMO soy, grown organically in the Japanese smallholder way. Soybeans have all eight essential amino acids in good balance. Lysine is the limiting amino, and you can get that from maize, which Guatemalans eat a lot of. Corn tortillas and boiled soybean frijoles make a complete protein, but in our camp in Solola we also made patés for babies, tofu, tempeh, soymilk, and, of course, ice cream. The image at the top of this piece is painted from a photo of Suzi Jenkins Viavant dispensing soy ice cream to schoolchildren in San Andreas Itzapa.

What my dear friend Bill was on about was something quite real; two things, actually. Because soybeans contain protease inhibitors that interfere with digestion activity, they have an antinutritional effect unless these inhibitors are deactivated. Whatever food you consume with them can be indigestible and give you a nasty stomach ache and gas. The inhibitors found in raw soy react primarily on trypsin, and chymotrypsin and plasmin to a lesser extent. Wild animals usually learn that any plant that contains a trypsin inhibitor is a food to avoid. Before feeding soy to cattle, it is ground into meal and heat-treated to remove the inhibitors.

Other foods containing protease inhibitors are lima beans (6 different inhibitors); winged beans; mung beans; raw egg white; and bovine pancreas and lung.

In a kitchen setting, boiling soybeans for 14 minutes deactivates about 80% of the inhibitors. Boiled 30 minutes, about 90%. At higher temperatures, e.g. in pressure cookers, shorter deactivation times are needed to reach 100%. When making soymilk, tofu and tempeh, good pre-cooking is part of the process. Any soybeans cooked well or fermented will be completely digestible.

To bring out the flavor in soybeans intended for burritos, lasagna, stroganoff, or burgers, they should be cooked until they are dark brown and soft enough to mash between your tongue and the back of your teeth. Straight from the boiling pot, they should melt in your mouth and have a buttery taste, smell, and feel. My experience with a pressure cooker tells me that proper cooking can take 90 to 120 minutes for rehydrated dry beans, and I always do the tongue-mash test.

The second point Bill made, and I agree with, is that the way soybeans are grown by industrial agriculture today is an abomination, leading to loss of family farms, biodiversity, topsoil and a habitable climate. The total area of soy now covers billions of acres — the total combined area of France, Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands. The fastest growth in recent years has been in South America, where production grew by 123 per cent between 1996 and 2004.

Soy produces more protein per hectare than any other major crop. It is also one of the most profitable agricultural products. Around 270 million tonnes were produced in 2012, of which 93 per cent came from just six countries: Brazil, United States, Argentina, China, India and Paraguay. Soy production is also expanding rapidly in Bolivia and Uruguay. The main importers are the EU and China, while the US has the greatest soy consumption per capita.

— World Wildlife Federation

The sad part is that 94% of this major world food crop goes into livestock feed or industrial uses and, counting vegetable oil and soy sauce, only 6% is consumed by people directly. When you feed it to cows, 98% of the nutritional value — the part that could be feeding people — is simply wasted. It is spent fattening a 350 pound-calf into a 1250-pound steer. Some of that can be recovered in the form of leather jackets or fertilizer, but a lot of it simply gets farted away as a greenhouse gas 87 times more powerful than carbon dioxide. Demand for soy in the EU uses 6 million square miles, 5.2 million of that in South America.

Nine out of 10 land-based species of animals and plants live in forests — the vast majority of them in the tropical forests of South America, Africa and Southeast Asia. Close to 1.6 billion people, including 60 million indigenous people, depend on forests for food, shelter, fuel and livelihoods. Forests provide vital ecosystem services, such as regulating water cycles, preventing soil erosion and helping to keep our climate stable: growing forests absorb and store carbon, but when they’re cleared, large amounts of carbon dioxide are released into the atmosphere. Half of the world’s tropical forests have been destroyed over the last century, and natural forests are continuing to decline in many parts of the world.

— World Wildlife Federation

Before Monsanto and Cargill, John Deere and Whole Foods, there was a habit of growing soybeans for 2000 years in China, Japan and Korea. In China today around 40 million farmers grow soy, with the average farm size being around 0.2–0.3 ha (half to three-quarters of an acre). By turning stover into biochar and returning manures (“night soil”) to the fields, soil fertility was maintained for 40 centuries. Thanks to the Asian Biochar Centre in Nanjing, farms across China are once more regenerating topsoil, retaining water, and re-learning these techniques. They are producing much higher yields today than they did just 5 years ago. Rotational smallholder cropping, with leguminous crops like soy restoring nitrogen, is the way of the future.

Using the power of soy in a regenerative, harmonious way, there is no food supply constraint holding human population from expanding ten-fold in this century. Other means will be needed to stop that.

In our next installment we’ll explore those means.

References:

Hwang, D. L., D. E. Foard, and C. H. Wei. “A soybean trypsin inhibitor. Crystallization and x-ray crystallographic study.” Journal of Biological Chemistry 252, no. 3 (1977): 1099–1101.

Liu, KeShun, Soybeans: Chemistry, Technology, and Utilization. Springer 2012.

Viavant, S.J., My First Experience in Guatemala as a Volunteer

https://munecaz.wordpress.com/my-first-experience-in-guatemala-as-a-volunteer-january-25-2014/

World Wildlife Federation. 2014. The Growth of Soy: Impacts and Solutions. WWF International, Gland, Switzerland

The COVID-19 pandemic has destroyed lives, livelihoods, and economies. But it has not slowed down climate change, which presents an existential threat to all life, humans included. The warnings could not be stronger: temperatures and fires are breaking records, greenhouse gas levels keep climbing, sea level is rising, and natural disasters are upsizing.

As the world confronts the pandemic and emerges into recovery, there is growing recognition that the recovery must be a pathway to a new carbon economy, one that goes beyond zero emissions and runs the industrial carbon cycle backwards — taking CO2 from the atmosphere and ocean, turning it into coal and oil, and burying it in the ground. The triple bottom line of this new economy is antifragility, regeneration, and resilience.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

#RestorationGeneration

“There are the good tipping points, the tipping points in public consciousness when it comes to addressing this crisis, and I think we are very close to that.”

— Climate Scientist Michael Mann, January 13, 2021.

Want to help make a difference while you shop in the Amazon app, at no extra cost to you? Simply follow the instructions below to select “Global Village Institute” as your charity and activate AmazonSmile in the app. They’ll donate a portion of your eligible purchases to us.

How it works:

1. Open the Amazon app on your phone

2. Select the main menu (=) & tap on “AmazonSmile” within Programs & Features

3. Select “Global Village Institute” as your charity

4. Follow the on-screen instructions to activate AmazonSmile in the mobile app

Comments