The Great Pause Week 51: Chalupas Chapulines

"Grasshopper powder contains 72% protein, all essential amino acids, and a balanced ratio of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids."

|

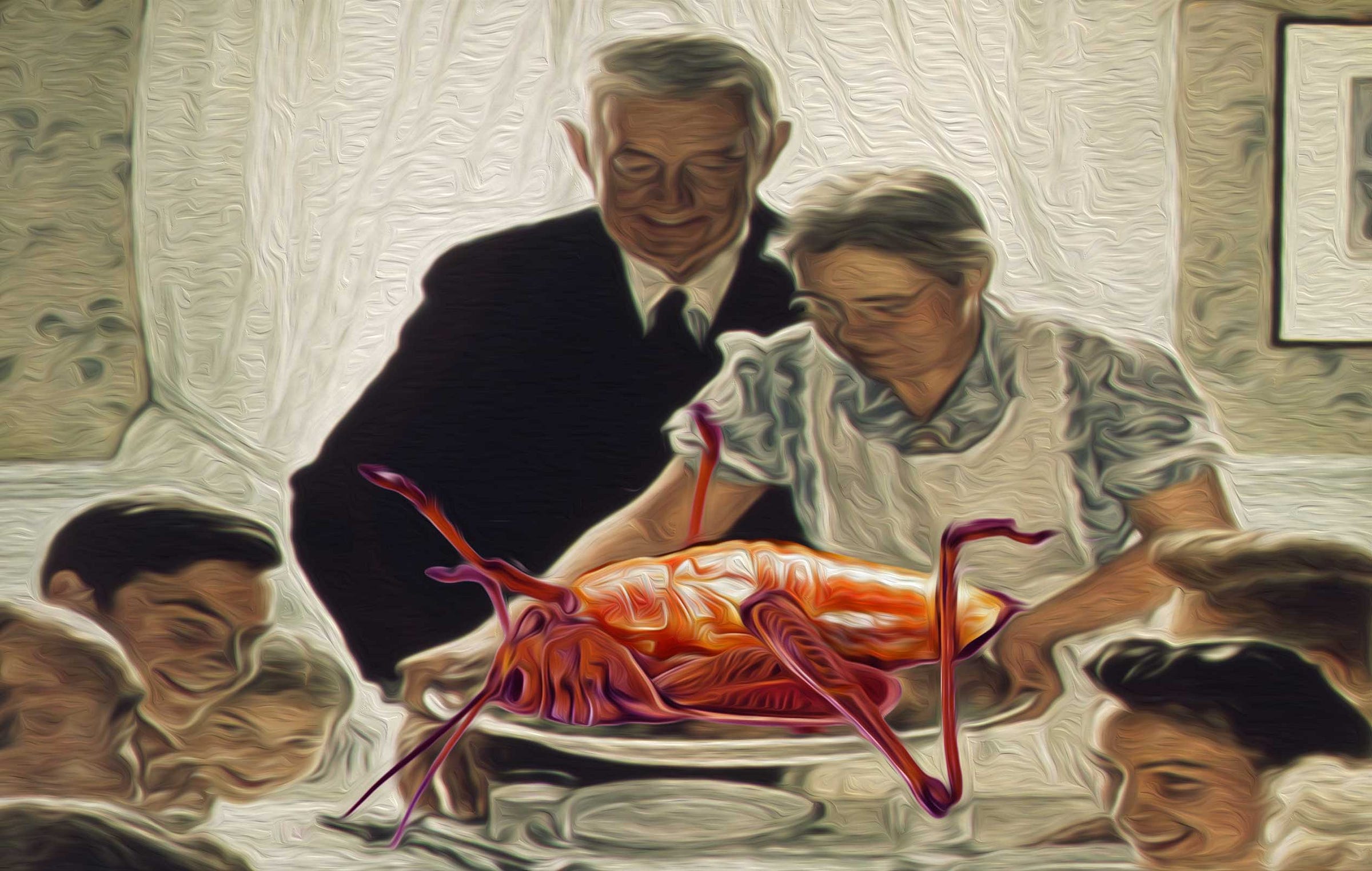

after Norman Rockwell, Freedom From Want — U.S. National Archives and Records Administration |

Eating bugs is nothing new. I often see confusion on vegan friends’ faces when I point out that:

- Every fork-, spoon-, or chopsticks-full of food they shovel in their pie-hole contains over a billion animals, some of which have eyes and try to get away.

- Most, if not all of these feel pain, avoid it when they can, and do not want to die.

- Ethically distinguishing the animals you will or won’t consume by their size is a dubious proposition. By that logic it would be better to eat an elephant or a whale than a snail or an oyster. Seriously?

Such fun aside, by 2050 food production will have to grow by more than 70% to meet Earth’s human population, but the farmland needed to produce that food won’t exist. Much will have been drowned, desertified, degraded, and chemically euthanized. The old stand-by, beating forests into farmland, will have an uphill slog to find political traction in a time when trees are a critical part of the fight against climate change.

That is the real reason we’ll all need to eat lower on the food chain, and more efficiently. The same soybeans used to fatten a single steer can produce 10 times the amount of nutrient-dense, life-giving protein if devoted to tofu and tempeh.

Salmon farms are now the fastest-growing food production systems in the world, but those caged fish are fed a diet of land-intensive crops plus wild fish harvested at unsustainable rates.

Insects like cage-raised grasshoppers, beetles, crickets, and soldier flies already serve as a protein source in pet food and feed for livestock — and for humans to a lesser degree, but our commercial future holds for us insect delicacies at the gigaton scale.

Bug wrangling is still very niche, but it doesn’t require a lot of land for production, water, or capital. Founded in 2011 in Paris by scientists and environmental activists, Ÿnsect is now the world leader in natural insect protein and fertilizer production. The company makes premium, high-value nutriceuticals for pets, fish and plants. Robots feed, hatch, harvest, and process bugs grown in trays stacked in tall towers, with AI monitoring the environment to optimize the conditions, the principal feedstock is garbage, specifically local food waste. The factory produces no waste itself, with all parts of their tiny herds converted to protein or fertilizer. After power for the robots is offset by the carbon going into the ground, the factory is carbon negative.

Ÿnsect now has contracts worth $100 million with fish feed producers. This is significant because it is widely assumed and falsely promoted that as human population expands, farmed fish will fill the gap to prevent overharvesting of wild catch. That is false because most farmed fish are fed wild catch, and with the high feed conversion ratio of your typical salmon, around 1:1.2, farmed fish do more damage to ocean biodiversity than salmon trawlers in the Bering Strait.

A few years ago a group of scientists at UNAM in Mexico City compared the ecological footprint of three types of livestock that are most widely bred worldwide — cattle, pigs, and poultry — to new breeds of mini-livestock from the Orthoptera family (grasshoppers, locusts, and crickets).

Humanity’s most exploited food animals for the past 50 years have been cattle, packed into dense pens and fed antibiotic and hormone-laced maize and soy to speed weight gain. Cows, pigs, and poultry supply 302.5 million tons of meat worldwide, 12% of which comes from the USA. Twenty-six percent of the world’s land surface and 33% of global grain sowing area are used exclusively to feed cattle. Industrial cattle production also uses copious amounts of water, chemicals, and fossil energy.

Ruminants are very efficient in producing CO2 and methane (CH4). Overall, global livestock is responsible for 14.5% of greenhouse gas emissions, with ruminants accounting for 11.6% and cattle alone producing 9.4% (sheep and goats make up most of the rest). As your vegan niece may have reminded you in less than sweet terms, reducing beef burger consumption by half could significantly lower your carbon footprint and give her generation a chance to make it out of this century alive.

Insects, in the UNAM comparison study, have highly efficient metabolisms, moderate regeneration times, possess superior amounts of usable protein, have a lower impact on land, water, and climate, and are highly nutritious.

It was fitting that this ecological footprint research was carried out in a nation where grasshoppers and crickets for food and feed have been part of a traditional milpa regime since before the Columbian Encounter. In México, some 500 insect species are consumed daily, a quarter to a half of the total number of common food insects raised or hunted worldwide.

The UNAM researchers estimated that approximately 350,000 tons of wild grasshopper (Sphenarium purpurascens) biomass per year could be sustainably harvested just in México. Given the weight of your average bug, that is a lot of grasshoppers.

Whether to farm grasshoppers or catch them in the wild is no small question. Grasshoppers currently consume 16% of the world’s maize production (costing 220 billion dollars annually) and are the target of nasty insecticides, suggesting there is good reason to consider wild catch first. Wild grasshopper poachers are another reason — every year they trample down thousands of acres of valuable grains while trespassing in pursuit of their elusive quarry. But, with 8 billion human mouths to feed, there is an efficiency argument.

Farm-raised, grasshoppers (Acheta domesticus or potentially 6 other species) consume less than they do in the wild (penned feed conversion ratio is 1 kilo grasshopper to 1.17 grass, compared to 1:4 for free range — an average confined cow is 1:10). This speaks favorably for wrangling ‘hoppers in the corral, rather than in the arroyos.

Still, there are worrisome signs emerging from CAFO industries moving into this sector. Through manipulating temperature, humidity, light, ventilation and “more,” Israeli grasshopper farming firm Hargol Foodtech claims to have shortened the incubation time for eggs from 40 weeks to 2–4 weeks, and increased the number of life cycles from one per year to 10. “It’s about timing, it’s about climate, it’s about providing the right conditions at the right time,” a spokesman told AgFunder News. “This is getting us out of seasonal farming into intensive farming.”

Hargol’s CAFOs look very similar to chicken CAFOs — large climate controlled warehouses with cages stacked from floor to ceiling. Hargol facilities also have vertical walls of hydroponically grown wheat grass. But getting their product to market has proven difficult. There is a strong, unmet demand in México for whole grasshoppers for restaurants and delis, but import regulations are absurdly restrictive, as you might imagine. There is also a huge global market for pet food protein, but US and EU regulations are much more complicated and pet owners balk at the notion of feeding their loved ones creepy crawly things.

“You wont believe it. Grasshoppers are part of the natural diet of pets — cats and dogs and reptiles,” said the Hargol spokesman, “but when the pet owner thinks about their pet eating that, they find it disgusting.” For the Israeli company, US import regulations for food additives — virtually non-existent — make those the most simple and clear product choices, and there are sometimes even trade subsidies.

A cow that weighs 500 kg yields 28 to 60 kg protein (most of this weight would be water and to a lesser extent organs, tissue, bones, skin, etc.). Orthopterans, after their visit to the grasshopper abattoir, have a net protein yield of 75 to 100 kg per 500 kg of live bug — up to 20 percent of body mass. Factory farm CO2, CH4, and N2O emissions are also significantly lower (for methane it is zero). Grasshopper powder contains 72% protein, all essential amino acids, and a balanced ratio of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids.

México grows a lot of corn, but because it feeds half to cattle, it is a net maize importer, mostly from the USA and China. If it could switch to producing more grasshoppers, it could eliminate its trade imbalance. In fact, the UNAM scientists discovered, it could free up four times the amount of maize it imports, making the nation an exporter again.

The next time you go to the taco stand, see if they have any chalupas chapulines.

Grasshopper Chalupas

Serves 6

Ingredients

Guacamole

2 cloves garlic

1 large or 2 medium jalapeño peppers

1 small onion

1 large or 2 small tomatoes

1 sprig of fresh or 1/4 cup dried cilantro

2 large or 6 small avocados

1 lime

Pinch salt

Chalupas

2 cups (about 100) grasshoppers (the younger the better)

1/4 kilo of corn tortillas

250 grams of panela cheese

1 onion

2 tomatoes

2 green tomatoes

4 serranos chiles

1/2 cup oil

6 cups water

1 pinch of salt

3 cloves garlic

1 lime

Directions

Guacamole

Mince garlic, jalapeños, chiles, onion, and tomatoes. Finely chop cilantro. Coarsely mash avocados, squeeze in lime juice, combine other ingredients, and add salt to taste.

Chalupas

- Soak the grasshoppers in clean water for 24 hours. Boil them, then let dry. Substitutions include locusts, crickets, wild mushrooms, squash blossoms, huitlacoche (corn smut), and colorines (the flowers of the colorine tree, boiled first in salty water), sautéed

- In a frying pan or wok with hot oil, fry tortillas until soft and golden in color. Remove, dry excess fat and set aside.

- Fry grasshoppers in the oily pan until golden and crispy.

- Roast and remove the garlic, onion, tomatoes and chiles.

- Separate and blend the red tomatoes with 1 garlic and half an onion. Add salt to taste.

- Repeat the process to prepare a green sauce with green tomatoes. Sauté both sauces with the little oil remaining from frying the tortillas.

- Plate the tortillas, cover with red or green sauces, top with fried grasshoppers and crumbled cheese, with guacamole and a slice of lime on the side.

References

Wegier, A., V. Alavez, J. Pérez-López, L. Calzada, and R. Cerritos. “Beef or grasshopper hamburgers: the ecological implications of choosing one over the other.” Basic and Applied Ecology 26 (2018): 89–100.

_____________________________

The COVID-19 pandemic has destroyed lives, livelihoods, and economies. But it has not slowed down climate change, which presents an existential threat to all life, humans included. The warnings could not be stronger: temperatures and fires are breaking records, greenhouse gas levels keep climbing, sea level is rising, and natural disasters are upsizing.As the world confronts the pandemic and emerges into recovery, there is growing recognition that the recovery must be a pathway to a new carbon economy, one that goes beyond zero emissions and runs the industrial carbon cycle backwards — taking CO2 from the atmosphere and ocean, turning it into coal and oil, and burying it in the ground. The triple bottom line of this new economy is antifragility, regeneration, and resilience.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger subscriptions are needed and welcomed. My brief experiment with a new platform called SubscribeStar ended badly, with my judgement that they are not yet ready for prime time. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

#RestorationGeneration

“There are the good tipping points, the tipping points in public consciousness when it comes to addressing this crisis, and I think we are very close to that.”

— Climate Scientist Michael Mann, January 13, 2021.

Comments