The Great Pause Week 37: Thanksgiving

“They … brought us parrots and balls of cotton and spears and many other things… They willingly traded everything they owned… They were well-built, with good bodies and handsome features…. They do not bear arms, and do not know them, for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance. They have no iron. Their spears are made of cane… . They would make fine servants…. With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.”

— Jornada de Colon, 1492

Columbus did indeed subjugate the native peoples of the Caribbean. Bartolome de las Casas, a former slave owner who became Bishop of Chiapas, described to his church elders in Spain how Conquistadors tested the sharpness of blades on native peoples by cutting them in half or beheading them in contests. They also liked to toss them into vats of boiling soap. He wrote of suckling infants being lifted from their mother’s breasts to be dashed headfirst onto pikes or large rocks. “Such inhumanities and barbarisms were committed in my sight as no age can parallel,” he wrote.

In the province of Cicao, Columbus ordered all persons over 14 to supply at least a thimble of gold dust every three months. Those who did not fulfill their obligation had their hands cut off, which were tied around their necks while they bled to death — some 10,000 died handless. In two years’ time, approximately 250,000 Indians on Hispañola were dead. Many deaths were from mass suicides or mothers killing their babies to avoid their torture. In the Caribbean settlements butcher shops sold Arawak, Taino, and Carib bodies for dog food. There was also the montería infernal, a manhunt in which Indians were hunted by dogs that wore armor and were raised on human flesh. Live babies were fed to these war dogs as sport, sometimes in front of their horrified parents.

Thanks to Bishop Bartolome’s reports and the injunctions of the Catholic church, a Royal Commissioner was sent to Hispañola to arrest the Admiral and bring him back in chains. After trial he was pardoned by King Ferdinand who subsidized a fourth and larger voyage of conquest.

Humans have a propensity to mythologize. Storytelling serves an evolutionary function. It alerts those of us who may not not have directly experienced some hazardous or fortunate event to remember the experience, should we personally encounter something similar in the future. Storytelling elevates our group skill set.

Exaggeration is a storytelling craft that serves to embed the experience more viscerally. It stimulates the memory’s filing system to prioritize some memories over others — to place them in a red folder for faster retrieval. Societies and ethnic cultures develop myths and propagate them by teaching (or frightening) children or embedding lessons in rituals that are observed in season or on occasion. Sometimes the myths evolve over time and become more lurid, fanciful, or real-sounding.

Thanksgiving is like that. Those who don’t travel may never have encountered it, or may not know it is only observed in Australia, Brazil, Canada, Grenada, Liberia, Netherlands, Philippines, Saint Lucia, and the United States. There are similar holidays in the UK, Germany, India and Japan, although rituals of gratitude are universal. The celebration of a successful harvest with a grand feast likely extends back into pre-history. We know it existed among the tribes of Turtle Island prior to the 17th century.

The English Reformation reduced the number of church holidays to 27, but some Puritans completely eliminated even those, including Christmas and Easter. They did, however, commemorate events that were thought to be a punishment or blessing from God by later observing them as days of fasting or days of feasting. Among memories thus preserved were the English drought of 1611, the floods in 1613, the plagues in 1604 and 1622, victory over the Spanish Armada in 1588, and the failure of the Gunpowder Plot in 1605. Guy Fawkes Day November 5 comes from that last one. When settlers arrived in Canada, they observed a harvest thanksgiving that was later made a legal holiday every 2nd Monday in October. Epidemiologists are tallying the death toll from this year’s observance. In Brazil it’s the 4th Thursday in November, with caskets still to follow.

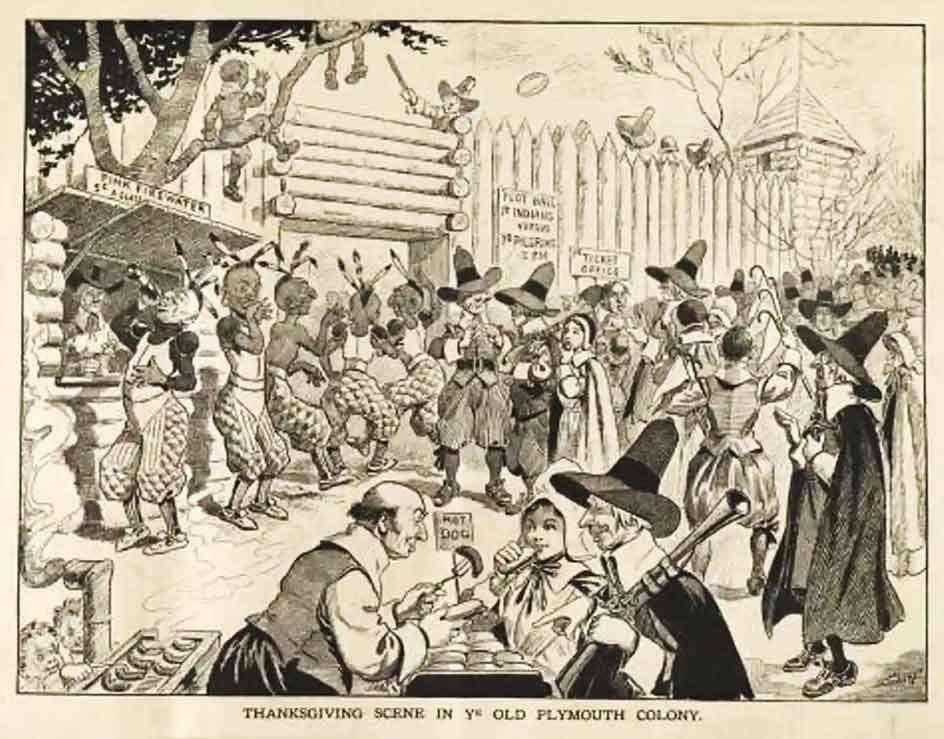

The United States really went overboard in its mythologizing, using Thanksgiving to paper over historic cruelty towards native peoples and genocide of unparalleled scale. Children are still given to associate the day with a Norman Rockwell painting of turkey dinner or a picture of Indians welcoming European settlers to the Americas with gifts of corn and feasting on wild game. The national myth serves to legitimize theft, wasting, and murder because the Pilgrims were merely shouldering their “white man’s burden” (Kipling) of bringing civilization and religion to savages.

No exaggeration is required to tell the true story. It is what should actually be taught to children for the lessons it holds.

When the Mayflower departed England in September 1620 it had 102 passengers aboard a relatively small ship. Only about a third were religious zealots. The rest were adventuring immigrants and land speculators. There were a number of “second sons,” members of the gentry who would not inherit fortunes but were well educated and hoped to build their own fortunes where land and resources were free for the taking.

“Young scions were then pushed out from the parent-stock and instructed to explore fresh regions and to gain happier seats for themselves by their swords.”

— Thomas Robert Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population 1798

On the two month crossing, despite the confined quarters and poor diet, only one passenger died and one child was born. Departing in September was a really bad idea, however. In the first place, that was the middle of hurricane season, so getting across the ocean unscathed was only through sheer luck. In the second place, they arrived in November, too late to plant crops and the provisions they had for their voyage were nearly gone. Lost at sea, the Mayflower failed to arrive at Jamestown, Virginia as planned. Instead, it heeled up on the sandy spit of Cape Cod.

If spending a provision-less winter in snowy New England wasn’t bad enough, imagine spending it in tents and lean-tos on the tip of Cape Cod, exposed to Atlantic storms. They robbed the graves of native peoples in search of anything edible.

That area was once Patuxet, a Wampanoag village now abandoned. Before 1616, the Wampanoag numbered 50,000 to 100,000, occupying 69 villages scattered throughout southeastern Massachusetts and eastern Rhode Island. Plagues brought by whalers, trappers, and slavers had already killed two-thirds of them.

By the time spring arrived, only 44 of the English remained, and those only because the Wampanoag noticed their plight and intervened to share their valuable winter rations. Pilgrim men ate first. Of the eighteen women that came with their husbands, all but five died — a 72% death rate.

Among the Wampanoag was a former slave who had been exported to Spain. He had learned to speak English in order to escape and return on an English vessel, but on his return he discovered his entire tribe had died resisting slavery or from European diseases. His name was Squanto. He offered to serve as an interpreter for the colony’s elected governor, William Bradford, and to negotiate favorable trade and defense treaties with Massasoit, the chief of the Wampanoag Nation. Squanto also taught the Pilgrims to gather chestnuts, walnuts and beechnuts and the farming techniques required to produce reliable crops of flint corn, beans, garlic, pumpkins and squash.

Having been to Europe, Squanto may have believed and would have advised Massasoit that armed resistance to the invasion was futile, although at that time the Wampanoag could have crushed the invasion as easily as crushing straw in the palm of your hand. But Massasoit realized that their only chance to remain and survive in their traditional home would be through diplomacy and alliance.

The generosity of the Wampanoag supplemented the food supply of the Pilgrims until they could grow and harvest what they required and in 1621 Massasoit and about ninety other Indians joined the Pilgrims for the tradition of harvest festival, dining on venison, goose, duck, turkey, lobster, fish, soups, stews, porridge, and cornbread. US historians and the Encyclopedia Britannica say the tradition was repeated every year. Wampanoag tribal historians say it never happened again.

Mashpee Wampanoag Tribal Historic Preservation Officer Ramona Peters, interviewed in 2017 for Indian Country Today, said, “It was Abraham Lincoln who used the theme of Pilgrims and Indians eating happily together. He was trying to calm things down during the Civil War when people were divided. It was like a nice unity story.”

In 1636, a murdered settler was found in his boat and the colony decided to blame the neighboring Pequots. The colonists burned the Pequot village on the Mystic River and killed all 700 men, women and children. William Bradford wrote:

“Those that escaped the fire were slain with the sword; some hewed to pieces, others run through with their rapiers, so that they were quickly dispatched and very few escaped. It was conceived they thus destroyed about 400 at this time. It was a fearful sight to see them thus frying in the fire…horrible was the stink and scent thereof, but the victory seemed a sweet sacrifice, and they gave the prayers thereof to God, who had wrought so wonderfully for them.”

The day after the massacre, Bradford wrote that “from that day forth shall be a day of celebration and thanks giving for subduing the Pequots” and “For the next 100 years, every Thanksgiving Day ordained by a Governor was in honor of the bloody victory, thanking God that the battle had been won.” Massacres are almost invariably labeled as “battles,” as they were at Sand Creek, Wounded Knee, Lawrence Kansas, Blair Mountain, Cajamarca, Mÿ Lai, Panama City, and El Mozote.

Bradford was only following in the tradition of Columbus, whose barbarism appalled even the Pope. A law unto himself, there was no Pope or King to sanction the Massachusetts Governor.

For USAnians and many other nationalities, Thanksgiving is a time of coming together and family reunions. There is much handwringing in this time of plague that sadly many will not be reunited this year. When we pause now, instead, to consider what was really being celebrated, maybe it is for the best that we take an overdue time out.

For me the lesson of Columbus and Bradford should be that no man is above the law, no matter what elevated station they attain. Failure to sanction their heinous offenses only insures the crimes will be repeated. Maybe we should reserve our thanks for when myths get shattered and justice prevails.

The COVID-19 pandemic has destroyed lives, livelihoods, and economies. But it has not slowed down climate change, which presents an existential threat to all life, humans included. The warnings could not be stronger: temperatures and fires are breaking records, greenhouse gas levels keep climbing, sea level is rising, and natural disasters are upsizing.

As the world confronts the pandemic and emerges into recovery, there is growing recognition that the recovery must be a pathway to a new carbon economy, one that goes beyond zero emissions and runs the industrial carbon cycle backwards — taking CO2 from the atmosphere and ocean, turning it into coal and oil, and burying it in the ground. The triple bottom line of this new economy is antifragility, regeneration, and resilience.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. Please help if you can.

Comments