The Measure of a Man in 120 Breaths

"“It has been a disappointment to me that so many people, including all too many environmentalists, thought the spirit of liberation of the 1960s was and is dispensable.” — Jan Lundberg"

One mark of a life well spent might be whether anyone takes a moment to write or say something publicly to note your passing. You could easily estimate the number of breaths that effort takes, in this case about 120. One hundred twenty breaths to sum up a person’s life.

On

this autumn week of 2018 Jan Lundberg shed his painful, cancer-riddled

mortal coil. He had been non-violently resisting his killer for several

years using diet, exercise and fasting. His mind had overcome his pain

but the disease had claimed his speech and strength and in the end he

fell after he chose to rise one last time, perhaps to go to the window

and look out towards the calm, blue ocean waters he knew so well.

He

was born to an ocean view in Baja California in 1952. His father had

driven his mother down from their 3-acre ranch in the San Fernando

Valley into México for the birth.

My parents had three reasons: medical freedom surrounding birth, Mexican nationality for owning land on the coast, and being able to stay out of the U.S. military should I need to do so, through Mexican citizenship.

Despite

often being badly treated when his father would fly into a drunken

rage, Jan admired his parents. He wrote of his father:

Dan Lundberg and I have in common these penchants: being the muckraking journalist, fasting for health, growing organic food, disdaining institutions, enjoying movies and plays, and setting out our individual future according to scripts we write for ourselves and loved ones along with anyone who might get close…. I owe to him my zeal, self-confidence and skills.

If you have watched the Amazon Prime series, The Romanoffs,

you may appreciate that Jan could have been in that as a character in

one of his father’s screenplays. Dan Lundburg’s Swedish mother could

have been a Romanoff heiress, were she not illegitimate. Dan’s first

love was writing movie scripts and stories. His autobiographical novel, River Rat, published in 1942, was described by Jan as a cross between The Catcher in the Rye and Gidget. It would fit right into that Romanoff story line.

Jan’s

father moved to México City in 1938 out of sympathy for the Loyalists

in the Spanish Civil War and divided his work between the US State

Department there and as a foreign correspondent for CBS. In 1945, the

32-year-old Dan Lundberg asked the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs

what a good career move for him would be. “Go into the stupidest

industry in the world,” said Standard Oil heir Nelson Rockefeller.

“What’s that?” asked Dan. “Why, the oil industry!”

Moving the family to Los Angeles, Dan got heavily into screenwriting (Gunsmoke, Jack Benny, World of Giants, and other productions), radio journalism, and promoting “Health Jubilees” about fasting and related modalities.***In the early 1950s Dan Lundberg created The Dan Lundberg Show, on KCOP’s (Copley Newspapers) Channel 13. Every Sunday evening for seven years, this “first talk show on television” competed in southern California with the national Ed Sullivan Show.

Dan’s

radio guests included Linus Pauling and Ray Bradbury, who in later

years told the father and son that despite living in L.A., he never

drove a car.

That shocked the father but impressed the son.

Making

his radio profile pay in more ways than one, the senior Lundberg became

a public relations consultant for gasoline marketers on the side. He

introduced self-service gasoline marketing to the Los Angeles area as a

way for independents to compete with the majors. That led to the Lundberg Survey as a retail price reporting service for gasoline marketers.

By the 1960s, the Survey

had become an industry standard and made the family wealthy. They

bought a mansion in the Hollywood Hills and a 39-ton yacht. Jan’s father

was able to put the newsletter on autopilot, so when Jan was a

pre-teen, the family set sail for 5 years, down the coast of México,

through the Panama Canal, and along the coasts of Colombia, Venezuela,

and Brazil, eventually through the Caribbean and up to the Bahamas. They

weathered Hurricane Dorothy on an 18-day Atlantic crossing until Jan

spied the volcanic peaks of the Azores on his 14th birthday. In

Gibraltar, Jan entered British Grammar School, affected a “to-ally

Bri-ish” accent and took up guitar, teaching himself “Yellow Submarine.”

From there his parents sent him to L’Ecole des Roches in Normandy.

It was here that I was awakened politically. I was asked by my dormitory leader Michel Blanc, “Que pense-tu de la guerre au Vietnam?” (What do you think of the war in Vietnam?) I replied, “Je n’aime pas la guerre.” He retorted, kindly enough, “Il n’y a personne qui aime la guerre.” In other words, English words, I was not being let off by saying I didn’t like war, because Michel was pointing out, “Nobody likes war.” I realized that I had to be against what the U.S. was doing in Vietnam, but I knew almost nothing about it.

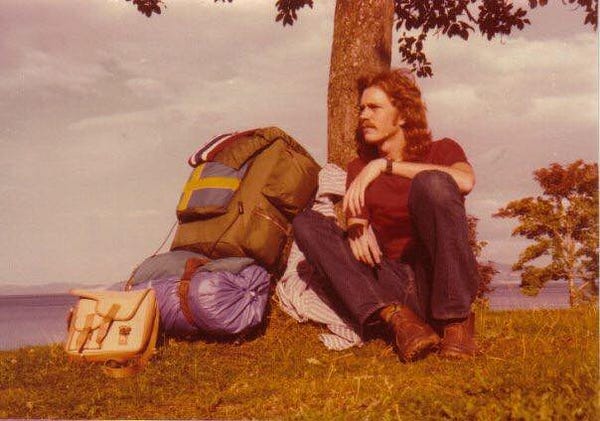

By

the summer of ’68, Jan was quickly shedding American parochialism and

becoming a world citizen. After a trip to Istanbul and later Palestine,

he mused, like Keats, that he had leapt headlong into poetry, and

thereby become better acquainted with the soundings, the quicksands, and

the rocks, than if he “had stayed upon the green shore, and piped a

silly pipe, and took tea and comfortable advice.”

I didn’t want to return to the States, having already reached that liberating decision. The English-speaking high school I attended and the jet-setting social circle I enjoyed were exhilarating, while I learned languages and believed I would always taste the delicacies of life.***I met Xenia Anagnostopoulou, whom I was to marry, in Overseas School of Rome. I can still remember sitting next to her by chance, during our 10th grade first-day orientation when we were 15 years old, and asking her name… Our high school romance began a year later when we coincidentally ended up in the same high school in Greece.

Jan

and I passed close to each other that summer, as I hitchhiked from

Luxembourg through Yugoslavia down to Mykonos and he and his family

sailed from Rome along the Dalmatian coast to Dubrovnik, through the

Gulf of Corinth and into Patras.

In

the autumn of 1969, shortly before returning to the US to attend

college at UC-Riverside and later UCLA, Jan attended a talk by

world-renowned architect and town planner Constantinos A. Doxiadis in a

downtown Athens hotel ballroom.

But my father stood up at the end, causing me to go pale in embarrassment, and asked a question of Doxiadis. It was something like, “Aren’t you condoning or contributing to the industrial destruction of the planet by paving over nature? Don’t we need a little nature?”

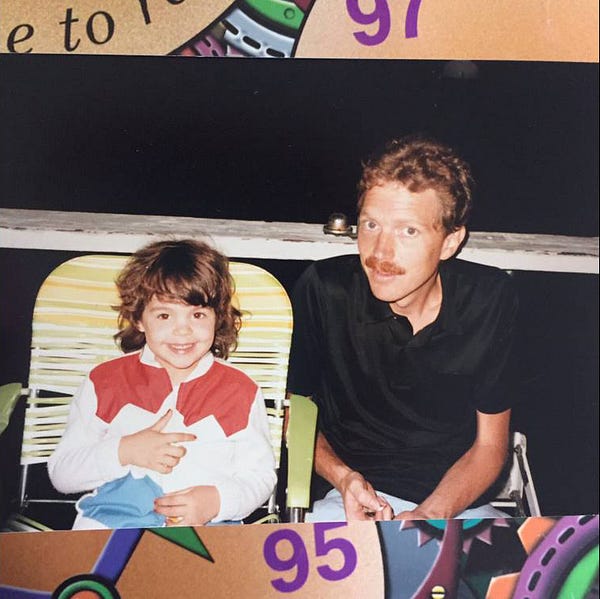

Jan’s

college career lasted just 2 years. At 19 he was drawn into his father’s

business. By 1978 he was running it. A newly sprouted mustache helped

him look older. In 1980, he and Xenia had a child, Vernell “Zoé” Zephyr

Lundberg, and Jan’s guitar work progressed from Bach to Pink Floyd. He

was a workaholic, though, and when he could not spend the time to take

the family for long stays in Greece, they divorced. He carried that

sadness with him the rest of his life, writing that, “Despite the

increasingly interesting work, the truly meaningful thing in my life was

being a father.”

My first job at the firm was actually during college, part time, 1970–1971, on every Friday night. Our team had to take down over the telephone the gasoline station survey-data from around the country, mostly just price changes for the grades of gas. It was an easy job and was suffused with camaraderie and free food.

In

those days they surveyed over 10,000 stations per month. With the

Iranian Revolution and the Second Oil Shock, Jan’s weekly Lundberg

Letter with alternative fuels surveys that set natural gas prices in the

US and abroad became much sought after, and made him real money. “I

hated the effects of my work but I loved my job and our prestige. Crazy,

huh?” he wrote.

In

1986 Jan celebrated the birth of his second child, Bronwyn, with his

new wife Heidi, and suffered through the death of his father. Although

given control of Lundberg Survey by his father’s will, by September he was out of the Survey, and soon would be out of the oil business forever.

When I found out about the present danger of global warming it was on a sweltering evening over dinner in the summer of 1988 in Washington with the chief economist of the Environmental Defense Fund, Dan Dudek. His bad news made me feel as if I lost some innocence as a child of the Earth. Yet this spurred me on to jump into the movement with all I had.

In August 1988, USA Today

ran his photo over a “Lundberg Lines Up With Nature” headline and the

story of a new global warming think-tank, Fossil Fuels Policy Action

Institute. Jan then launched the Alliance for a Paving Moratorium and

published the Auto-Free Times, later called Culture Change. He lost Bronwyn to Heidi’s acrimonious departure, but he got to have Zoé. He wrote:

My new life in 1989 saw me happily caring for my older daughter full time, I had my stimulating work, and I picked up the guitar again — and have not put it down since.

***

I realized I had made a mistake: I could have and should have used the settlement from Lundberg Survey to exit the business/nonprofit culture entirely. I could have bought a farm and got close to the land.

But

there were more pressing matters. In 1992, an historic warning by 1,670

eminent and honored scientists, including 110 of the 138 living winners

of Nobel prizes for science, was issued:

“We are fast approaching many of the Earth’s limits. Current economic practices which damage the environment cannot continue. Our massive tampering could trigger unpredictable collapse of critical biological systems, which are only partly understood. A great change in our stewardship of the Earth and the life on it is required if vast human misery is to be avoided, and our global home on this planet is not to be irretrievably mutilated.”

Jan later wrote of this:

Because this warning was not heeded, major tipping points have been crossed. I see humanity and our fellow species on an alarming slide down to an unknown and terrible chasm. Few people seem to realize or admit it.

Jan moved with Zoé from Virginia to Humboldt County, California and when not writing for Auto-Free Times and Culture Change launched

new projects. Zoe later recalled, “People could stay for free as long

as they bicycled in the produce to the Farmer’s Market every week. He

called it “Pedal Power Produce” and I remember painting the A-frame sign

for the booth. He taught me about organic food long before it was

trendy.”

From

1993 to 2001 he wrote about 350 stand-alone essays and reports and

published 20 magazine issues. From 2008 to 2011 he labored at his

self-published autobiography, Songs of Petroleum.

My findings and interests in both lifestyle and cultural change came through years of promoting transport reform and land-use changes so as to end urban sprawl, which I still push as secondary priorities.***

Getting the word out, even when fraught with negativity, seemed to be what I had been preparing for since a very young age. I was influenced greatly by my father’s example as a reporter, author and talk-show host. After ending my oil analysis career in 1988, I was soon to find that I had something positive and exciting to share.

***[S]ongs and the usual activism aren’t getting us very far — or so it only may seem, as countless seeds planted may still germinate and grow into a sustainable, just society. But perhaps we need a new idea, a new approach.

There are days when I believe it could it be right under our noses. Can lifestyle and culture change be presented as an appealing solution, or do we have to see collapse before people go into action and cope with even worse chaos?

When

Zoé was about to turn 16, the two traveled to Kerala, India, and then

out beyond the paved precincts into the upland tribal areas in the

Wyanad region. He wrote: “Vernell and I were in India only 3 1/2 weeks,

but it felt like much longer, and we wanted to stay.”

I was with Jan at the Petrocollapse Conference he hosted in Washington

DC in 2005, at any number of Association for the Study of Peak Oil

conferences over the years, including one at Cooper Union where we first

met Dmitry Orlov and Jim Kunstler. Jan and I were at the march against

the Dakota pipeline, in Zuccotti Park for Occupy Wall Street, and in San

Francisco to celebrate the Anniversary of the Summer of Love. He and I

boated across the Bay and hitchhiked up the coast to the Regenerative

Design Institute in Bolinas. In 2010 he trekked down to Belize to attend

the 2-week permaculture course Maria Ros and I gave at the Maya

Mountain Research Farm.

Like

few others, Jan understood that there are no technological or resource

impediments to solving the climate crisis. The only impediment is

people. The tools and methods we will use to surmount that obstacle are

the those he spent his life imagining, creating, and honing. He spent

most of his life trying to infect the human population with the virus of

simple living. Perhaps we could call it the antidote to consumer

culture. “Collapse now and avoid the rush,” he joked. In the

introduction to Songs of Petroleum, he wrote:

Demanding social justice is righteous, but our course must be well thought out; there are no second chances with a totally trashed ecosystem and climate. I have come to my assessment not just in my mind, based on research from various disciplines, but in my heart….

In my quest and environmental career I have adopted “simple living” and even veered toward what one might consider to be primitivism — how “green” can we be to match the ecosystem’s and our species’ real needs?

This

was a man who put his body where his words were. He invested everything

he had or would ever come by. In the end, when cancer crept up on him,

he abandoned the hospital course and fasted, choosing to return, at

last, to his beloved Greece, where his Sail Transport family took him in

and cared for him as he gradually lost his power to speak, and to walk,

and to write. His daughters came to visit with him and that gave him

his greatest joy.

But

no one was with him at that final moment, when, in desperate, exquisite

lucidity, he knew the end of this Greek drama was finally upon him, and

he raised himself up and stood one last time to stare into the heart of

this world he had known and loved.

Goodbye my friend.

Comments