Creative Loafing with Joe the Baker

|

Malthouse Couching by Andrea Gentl

|

While we have come to rely on experts for many things, most of what we want to achieve with the Great Change will not come from those. They will come from us.

Community design cannot be left to professional architects, engineers and planning officials alone but, once trained in whole-systems design, these professionals can become powerful change agents. Regenerative and sustainable communities emerge from the active participation of all (or most) of their members. Therefore, widespread education in community design and processes that stimulate civic engagement and community participation are essential.

— Daniel Wahl, Designing Regenerative Cultures (Triarchy Press, 2016).

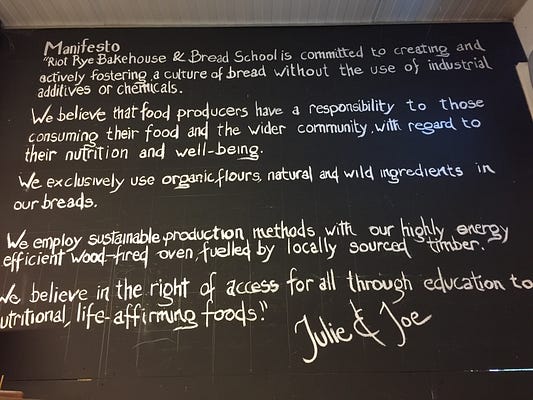

Joe Fitzmaurice and Julie Lockett are Riot Rye. Joe’s parents, Pauline and Joe, founded The Golden Dawn macrobiotic center in Dublin in the 1970s. His sister Lorraine set-up Blazing Salads, a whole-food/vegetarian restaurant in 1986 and then opened Blazing Salads Food Company with another sister, Pamela.

Joe Fitzmaurice and Julie Lockett are Riot Rye. Joe’s parents, Pauline and Joe, founded The Golden Dawn macrobiotic center in Dublin in the 1970s. His sister Lorraine set-up Blazing Salads, a whole-food/vegetarian restaurant in 1986 and then opened Blazing Salads Food Company with another sister, Pamela.

BSFC is a whole-food/vegetarian delicatessen with an amazing cookbook of the same brand. Brother Joe joined them as the baker, making rye, spelt and wheat sourdoughs for the deli.

In 2004, Julie visited Findhorn and after an infectious experience in ecovillage living persuaded Joe to join Cloughjordan Ecovillage. To sustain the move, they set out to create a small business that could support the family in a rural area, far from the bustling foodie scene of Dublin.

In 2004, Julie visited Findhorn and after an infectious experience in ecovillage living persuaded Joe to join Cloughjordan Ecovillage. To sustain the move, they set out to create a small business that could support the family in a rural area, far from the bustling foodie scene of Dublin.

Joe: “We wanted to look at having a wood fire oven and we got talking to this fellow who was from Tasmania, Alan Scott, blacksmith by trade and designed wood ovens. He got started by designing a better oven for Laurel Robertson of Laurel’s Kitchen fame in California. He traveled around looking at traditional French communal ovens and Quebec farmhouse ovens. He noticed that the ratio of the height of the dome to the height of the doorway was critical to the efficient firing of these ovens.

“Beech is one of the best woods for firing a wood-fired oven. The beech forest here was planted after the Second World War and beech is one of the best woods for baking. We got 50 ton of timber out the first year. Timber John has the contract to cut this forest. He takes it to Johnny Woodcutter who cuts it to the lengths we need.

“This year was the coldest its been in the last 7 years. Up until now the oven has never dropped below 100°C (212°F) — we can leave for a week or 10 days and it is still that hot when we come back.

“It takes 8 hours to fire the oven. We fill it a third with wood. We aim for 150 in the middle of the ceiling. There are 6 thermocouples, showing the layers from hot to cold. For this pizza night they are showing from 107 at the outer to 438°C at the inner right now. We’ll bake 150 loaves on average without having to re-fire. The most we’ve ever baked was 420 loaves on one firing.”

‘Did ye ever ate colcannon that’s made from thickened cream,With greens and scallions blended like a picture in your dream?Did ye ever take potato-cake or boxty* to the school,Tucked underneath your oxter with your book and slate and rule?

— Margaret Saunders, A Taste of Ireland

Julie: “We serve 250 households in this area. We sell everything locally. Our radius is the ecovillage and a few shops in Cloughjordan and a coop and café in Limerick and once a week to Nenagh and Roscrea. We run a bread club. Here in Cloughjordan people can buy our bread at a discount if they make a monthly standing order. The children take their wagon around the village and knock on the subscriber’s door or open the door and shout ‘Bread!’ and leave the sack.”

Joe: “We went for a black oven. It set the limits of our business. We can’t expand to 50,000 loaves per day. We can do 400. We fire this oven. That energy goes up there (points to the ceiling of the oven). It’s stored in the wall. When it gives up we’re done. We’re finished for the day. We don’t fire it up again. So we can’t bake any more than that. We can’t expand our business. We put a stop on how much we could grow our business, and that was a very conscious decision.

“A bakery used to have the market radius of as far as a horse could go and back in one day. That was the limit on a bakery. If there was lots of people in that area you could sell a lot and if there were few you’d sell less. Today there are bakeries in Dublin that ship off to New York and to Australia. It is not the same bread.

“We only bake 3 days a week at most. The usual rise is about 16 hours but it can vary. We work in the day, not at night, and the bread we bake lasts four days. It’s a bit like working on a Farm. Some days we will work 2 hours or 3 hours. Other days it is 14–15 hours, from 6:30 in the morning to 9 or 10 at night. Once all the bread is out you fill it up wood again so it can light easily again.”

When they first opened in 2011, the little oven shed next to their home was called Cloughjordan Woodfired Bakery. “Then someone brought us the rye taken straight from these fields out back here and we tried it and we loved it so now we are Riot Rye.”

Joe: “I don’t normally bake white bread anymore. I want the nutrition to come out of the earth. Now and again we will make special things, like pizza night, but we want to focus on the bread that comes straight from the earth and takes a long time to ferment. We only use wheat, rye and wild yeasts.

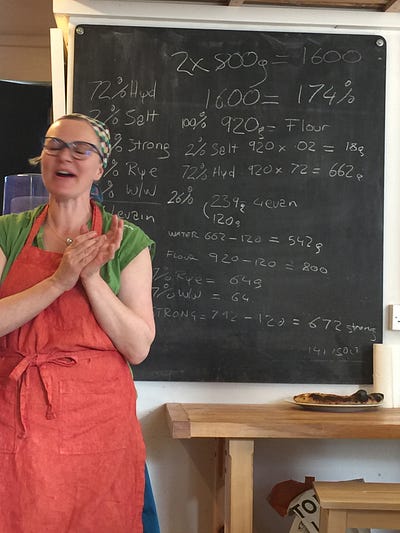

“Baking came out of two main historic themes — soda powder or cultured yeasts, and natural fermentation. In the natural fermentation you have lactobacillus bacteria and wild yeasts, and the bacterial feed on the proteins and break down the gluten and release the sugar and the yeasts will feed on the products from the bacteria and release carbon dioxide. Without the bacteria we don’t have the breaking down and releasing to feed the yeasts. There is an enzyme in the bran that will be chelated in the natural ferment but would remain in the other types of baking. Properly fermented bread will release all the nutrients and make them available for digestion in your body.

“So we need a long fermentation. It starts the day before, and allows the time to break down and release the nutrients.”

These enterprises and many others are helping to revitalise communities at the human scale where regenerative cultures can emerge. They all share two important insights: we can design as nature by deeply listening to and learning from the places we inhabit; and the first step towards creating regenerative cultures is to engage people in conversations to re-envision the future of the communities they live in. To do this we also have to re-envision our systems of production and consumption.

— Daniel Wahl, Designing Regenerative Cultures

Julie: “We don’t want to develop it as a business to where I spend more time on the computer than I have with my kids. And Joe says he doesn’t want to have to do this every day, but he enjoys it with the days each week that he has now. And he would rather be baking than selling.”

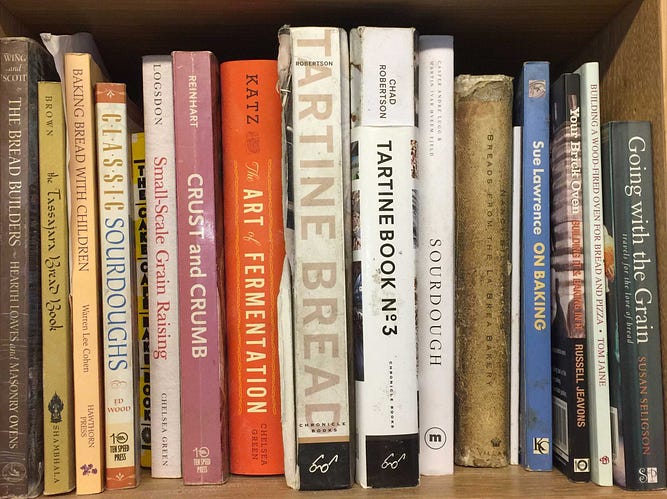

Joe: “My community of bakers is worldwide — Ireland, UK, San Francisco, Tasmania, Denmark, Germany. When you work at the scale we work we can share information about the things we discover. It used to be very hierarchical and lots of secrets, but now the information is democratized. We actively share knowledge with each other. We have to get lots of knowledge out there to allow baking to shift to this scale of production.

Joe: “My community of bakers is worldwide — Ireland, UK, San Francisco, Tasmania, Denmark, Germany. When you work at the scale we work we can share information about the things we discover. It used to be very hierarchical and lots of secrets, but now the information is democratized. We actively share knowledge with each other. We have to get lots of knowledge out there to allow baking to shift to this scale of production.

“The important thing is that it stays local. You can try a recipe from San Francisco that makes a crisp crust and really big holes, and you can order their sourdough starter, but you would have to get their local grain to make it work right. And their wild starter is not your wild starter. You are likely going to get something completely different.

“We have lost a heritage of Irish grains because people came to think they were no good. We don’t have the experience or the confidence to allow our grains to stand up against the mass-produced grains we import now.”

Joe and Julie are founding members of Real Bread Ireland to help spread the craft of local baking.

“We just want to enable everybody to have access to really good bread. And I just want to make a really good loaf every time.”

Update: In the early hours of the 22nd August 2017 the ecovillage barn was razed to the ground in a huge fire. You can help with a small donation to the rebuilding!

Rye Sourdough Starter

This starter takes one week to develop and then will last in perpetuity. Download the Riot Rye PDF to print this.

You will need:

— Container (1 liter) with lid (a kilner jar is a perfect shape, however, do not lock the jar as carbon dioxide is produced during fermentation and needs to escape. If the container you choose is too wide, during the initial stages the starter may be liable to spread too thinly and inhibit fermentation)

— Scales (digital preferably)

— 325g Organic Wholemeal Rye Flour

— 325g Water

Day 1

25g Organic Wholemeal Rye Flour

25g Water

25g Water

In your container, mix the flour and water together so that there are no dry bits, cover with the lid and leave in warm place (21–25°C or 70–77°F), a warm part of your kitchen should be fine or your hot press.

The wild yeasts and bacteria on the flour will then begin to ferment the flour and after a couple of days you should notice a slight sour smell and taste and also some air holes.

Day 2

Leave

Day 3

You are now going to refresh your starter by adding more flour and water to your juvenile starter. As the fermentation process has begun, this addition will ferment more quickly.

Add 50g Organic Wholemeal Rye Flour

50g Water

Mix the flour and water together so that there are no dry bits, cover with lid. Leave in warm place (21C-25C or 70–77°F).

50g Water

Mix the flour and water together so that there are no dry bits, cover with lid. Leave in warm place (21C-25C or 70–77°F).

Day 4

As you build up the beneficial bacteria and wild yeasts, you do so by keeping 1/3 starter and refreshing it with 1/3 flour and 1/3 water. To prevent from being over-run with and having too much excess starter you discard some.

As you build up the beneficial bacteria and wild yeasts, you do so by keeping 1/3 starter and refreshing it with 1/3 flour and 1/3 water. To prevent from being over-run with and having too much excess starter you discard some.

Compost 100g of starter keeping 50g

Add 50g Organic Wholemeal Rye Flour

Add 50g Water

Mix the flour and water together so that there are no dry bits, cover with lid. Leave in warm place (21C-25C or 70–77°F).

Add 50g Organic Wholemeal Rye Flour

Add 50g Water

Mix the flour and water together so that there are no dry bits, cover with lid. Leave in warm place (21C-25C or 70–77°F).

Day 5

Compost 100g of starter keeping 50g

Add 50g Organic Wholemeal Rye Flour

Add 50g Water

Mix the flour and water together so that there are no dry bits, cover with lid.

Leave in warm place (21C-25C or 70–77°F)

Add 50g Organic Wholemeal Rye Flour

Add 50g Water

Mix the flour and water together so that there are no dry bits, cover with lid.

Leave in warm place (21C-25C or 70–77°F)

Day 6

You are now going to build up enough starter so that you can make your bread tomorrow.

Add 150g Organic Wholemeal Flour

Add 150g Water

Mix the flour and water together so that there are no dry bits, cover with lid

Leave in warm place (21C-25C or 70–77°F).

Add 150g Water

Mix the flour and water together so that there are no dry bits, cover with lid

Leave in warm place (21C-25C or 70–77°F).

Day 7

Make the ‘Common Loaf’.

The recipe for the ‘Common Loaf’ uses 300g starter.

Whenever you make the ‘Common Loaf’, you will use 300g of starter and the remaining 150g should be stored in your fridge for your next bake.

Whenever you make the ‘Common Loaf’, you will use 300g of starter and the remaining 150g should be stored in your fridge for your next bake.

Next time

12hrs before bake

Repeat from Day 6

Repeat from Day 6

Porter Cake

Adapted from Theodora-Fitzgibbon, A Taste of Ireland (1970)

from Margaret Saunders (b. 1875), Carrick-on-Suir, Co. Tipperary

|

| Liffey Riverfront, Dublin |

In Dublin the best ales traditionally came from the country, arriving by flatboat down the River Liffey and off-loaded to Temple Bar establishments like the PorterHouse. The ale was carried off the boats by longshoremen walking up planks with a cask on their shoulder. These heavyset men were called porters, hence the name of the distinctive artisanal ales. The heavier, darker ales had greater gravity and required especially stout porters to shoulder the casks, and thus we get stout.

Ingredients:

1 lb (4 ½ cups) sifted cake flour

1 lb (2 ½ c.) brown sugar

1 lb (3 c.) seedless raisins or currants

½ lb (1 ½ c.) sultanas (Thompson seedless grapes in USA)

1 level teaspoon biocarbonate of soda, melted in warm porter

4 eggs

½ lb (1 c.) butter

4 oz (1 cup) glacé cherries

4 oz (1 c.) blanched chopped almonds

4 oz (1 c.) mixed chopped peel

½ pint porter or stout, warmed

grated rind of 1 lemon

pinch of mixed spice

1 lb (2 ½ c.) brown sugar

1 lb (3 c.) seedless raisins or currants

½ lb (1 ½ c.) sultanas (Thompson seedless grapes in USA)

1 level teaspoon biocarbonate of soda, melted in warm porter

4 eggs

½ lb (1 c.) butter

4 oz (1 cup) glacé cherries

4 oz (1 c.) blanched chopped almonds

4 oz (1 c.) mixed chopped peel

½ pint porter or stout, warmed

grated rind of 1 lemon

pinch of mixed spice

Rub the butter into the flour and add all the other dry ingredients. Blend very well. Beat the eggs with the lukewarm porter and add the bicarbonate of soda. Mix this very well into the dry cake mixture. [note: if you leave this to stand for a day or two, the wild yeasts and bacteria on the flour and in the porter will then begin to ferment the flour and after a while you should notice a slight sour smell. Alternatively, you could blend in some sourdough starter and let stand for 8–10 hours. This adds in the element of wild fermentation that Ms. Saunders left to the porter.] Turn the dough into a greased and lined cake tin, measuring 9 in. in diameter and 3 in. high. It should be covered with greaseproof paper and baked in a slow oven (200–250°F) for about 3 to 3 ½ hours, removing the paper for the last half-hour. Test with a skewer before removing from the oven. It makes a good Christmas cake and if iced will keep well in the tin.

*Boxty Bread

from 1879–80, Patrick Gallagher, Co. Donegal.

Boxty is a traditional Irish potato dish served on the eve of All Saint’s Day, All Hallows’ Eve (before El Día de Muertos).

Ingredients:1 lb raw potatoes

1 lb (4 c.) flour

1 lb (2 c.) cooked mashed potatoes

4 oz (1/4 c.) melted butter or bacon fat

salt and pepper

1 lb (4 c.) flour

1 lb (2 c.) cooked mashed potatoes

4 oz (1/4 c.) melted butter or bacon fat

salt and pepper

Peel the raw potatoes an grate into a clean cloth. Wring them tightly over a basin, catching the liquid. Put the grated potatoes into another basin and spread with the cooked mashed potatoes. When the starch has sunk to the bottom of the raw potato liquid, pour off the water and scrape the starch onto the potatoes. Mix well and sieve the flour, salt and pepper over it. Finally add the melted butter or fat. Knead, roll out on a floured board and shape into round, flat cakes. Make a cross over, so that when cooked they will divide into farls. Cook on a greased baking sheet in a moderate oven (300°F) for about 40 minutes. This quantity will make about four cakes. Serve hot, split in two with butter.

We post to The Great Change and Medium on Sunday mornings and 24 to 48 hours earlier for the benefit of donors to our Patreon page. Albert Bates will be traveling and speaking later this year at Web Summit-7 in Lisbon, COP-23 in Bonn, IPC-13 in Hyderabad, and ESP-9 in Shenzhen.

Comments