The Great Pause Week 26: Beer Cascades

"The Scots forest smallholding system is inherently democratic. It encourages innovation and prevents exploitation and waste."

Last week we looked at the Scottish distillery & pub chain BrewDog and its pledge to remove twice as much carbon from the air as it emits every year. It is buying carbon offsets until it can ramp up its reforestation strategy and it has purchased, with crowdsourced punk equity, 2,050 acres just north of Loch Lomond, where it will restore 1400 acres of native woodlands in the highlands and 650 acres of peatland in the lowlands. One of the premiums for punks who contribute will be access to the BrewDog Forest nature camp for hiking, partying, and retreats.BrewDog’s reforestation design goals, besides carbon sequestration, are biodiversity, natural flood attenuation and rural economic development. I cannot begin to express how important these other goals are. If you’re narrowly focused on hauling down CO2, you could, through dumb design, plant acres of non-native monocultures. That is not a forest. That is an impoverishment.

Not long ago I watched Outlaw King, a 2018 fictional recreation of how Robert the Bruce III, ancestor of Prince Charles, liberated Scotland from England in the early 14th Century after the martyrdom of William Wallace, as depicted by Mel Gibson in Braveheart. The filmmakers laid in many long sweeping shots of grassy highlands. I had to ask Mr. Google if it was true that Scotland was barren of trees in that time. “T’was,” He said.

The felling of trees didn’t wait for the clearances of the clans to make room for English sheep. They began in Roman times. The Caledonian Forest dates to the last glaciation ending about 7000 BC. It reached its maximum extent about 2000 years later when the climate warmed wetter and windier. For millennia, wildlife and humans flourished in a mosaic of trees, heath, grassland, scrub and bog until the dawn of herding and agriculture. There stands a yew in Glen Lyon estimated at 3000–5000 years, before hieroglyph was first set to papyrus in Egypt.

Yet, by the time the legions of Rome defeated the Caledonians in AD 82, at least half the forests were gone, felled to build homes and barns and heat them in the long dark winter months. The Romans did their best to harvest and export the other half.

By the time of the Industrial Revolution there was still enough forest left in Scotland for charcoal to cold-filter whiskey and feed the blast furnaces of Birmingham. Then, in the 1919 to 1927 period, with a world reeling from the twin disasters of trench warfare and the Spanish Flu, two British lords, Simon Fraser and John Stirling-Maxwell, launched a plan of land-settlement allied to forestry that could still serve as an ecovillage/eco-regions blueprint today.

Fraser and Maxwell created smallholdings of approximately ten acres, let for £15 a year. With men and women to care for the small trees and companion livestock and crops, the holdings were a great success and filled a genuine need in the rural countryside when Scotland entered the Great Depression.

“In practice, of course, these smallholdings attracted the cream of our men whom we were glad to employ on full time….”

Later government studies saw the program more as harm prevention than a profitable enterprise, reporting that it “was never a directly economic proposition, but in the pre-war days when motor traffic was lacking and it was much more important than today to have a solid caucus of skilled woodsmen living in the forests, the indirect benefits were inestimable.” (Ryle, Forest Service, 1969)

The Scots forest smallholding system is inherently democratic. It encourages innovation and prevents exploitation and waste. From 1934 and onwards the government recruited woodsmen, including the Women’s Timber Corps, groups of conscientious objectors, and workers from Belize to replenish lost highland forest and improve timber stands.

Unfortunately, these battalions of the underemployed ignored the 31 species of deciduous trees and shrubs native to Scotland, including ten willows, four whitebeams and three birch and cherry and a hundred other species so prized by the smallholders (and by pine marten, twinflower, crested tit, Scottish crossbill, black grouse, capercaillie and red squirrel). Instead, they covered almost half of the all forest land in the country with Sitka spruce and another 20% with Douglas fir, lodgepole pine, larches, and Norway spruce. The government foresters seemed to be preparing for another Ice Age.

This has left a gaping hole in the cultural fabric for the BrewDog punks to fill.

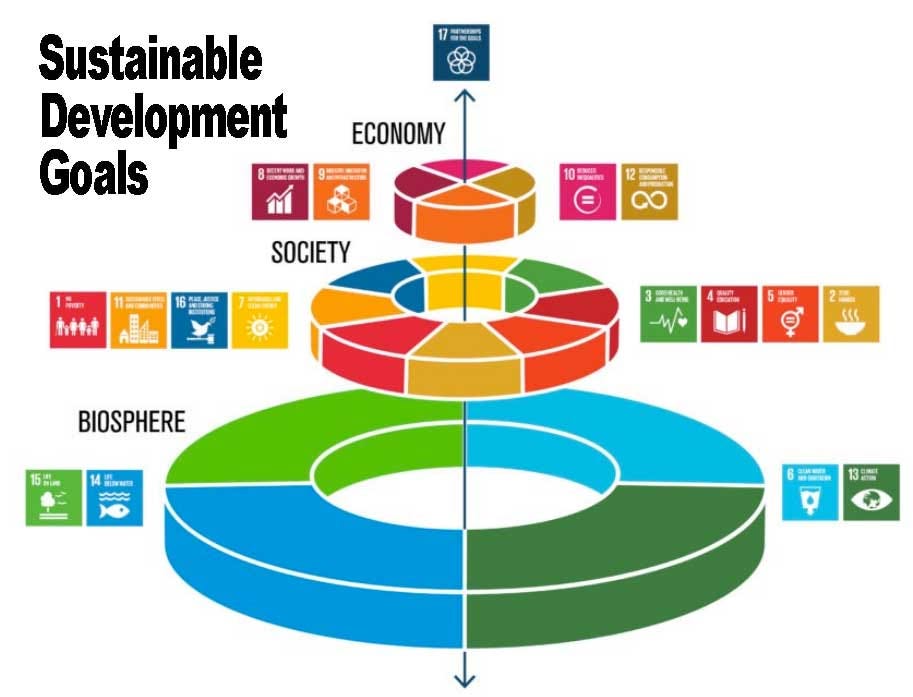

Most scenarios that achieve the Paris targets of limiting catastrophic heating to 1.5°–2.0°C rely on large-scale carbon dioxide removal (CDR) to drive net emissions negative after mid-century. Scenarios that overshoot emissions in the first half of the century must return Earth to the Paris temperature target or some barely habitable climate still within reach, by going strongly negative in the second half. This strategy is sort of like underdog Muhammed Ali doing Rope-A-Dope for 8 rounds in the Rumble in the Jungle or Silky Sullivan falling 41 lengths behind the field only to run the last quarter mile in 22 seconds. For this Hollywood-style come-from-behind finish, conversion to renewables and near-term experiments in CDR need to start now and prepare to ramp up rapidly, much the same way Big Pharma is prepping its vaccines. Once the best CDR methods are proven, they’ll need to operate for a century or so and become ubiquitous — an investment involving financial flows of billions to trillions of dollars per year.

And that’s the world’s plan. You can argue that it is a bad plan. You can say that CDR is fairy dust. You can point out that nobody in their right mind would take such a risk on the habitability of the whole planet, but that’s our designated plan. It wasn’t crafted, drafted, negotiated, and voted. It is the default result when you can’t negotiate and vote something meaningful because wealthy interests are spending billions to make sure you can’t. That, and the neurological discount factor Homo Sapiens evolved even before the last glaciation.

Variation among the different CDR methods’ constraints of scale, cost, or profit structures suggests governments and financial institutions will likely produce some rough ordering of these methods over the next decade or two. After studying this subject for many years, my best guess is that the low hanging fruit will shake out to be the natural varieties of negative emissions technologies (NETs) such as tree planting and conversion of photosynthetic wastes (from aquaculture, forestry and agriculture) to biochar and all its value-chains of products. The leading study on that in 2017 concluded we could pull 11.3 billion tons of CO2 from the atmosphere and ocean annually by 2030, at a marginal profit, and double that if we paid carbon credits and subsidized the drawdown at $100/ton. If the switch to renewables will bring man-made emissions down from 40 billion tons per year to half or a quarter of that by 2030, NETs could be actually pushing us back into a comfortable Holocene climate by mid-century, although admittedly there are still a lot of unknowns.For the BrewDog punk foresters this will be an opportunity to tap more potentials from their ecological restoration of the highlands, lowlands and other locations. A single tree can sequester 100 tons during its lifetime. If it falls and rots on the forest floor, all that goes back to the atmosphere. If it burns in wildfire, a large part will go back to the atmosphere. If it is harvested before it dies or is changed into biochar when it does, that 100 tons becomes a credit in the climate bank. By step harvesting — overplanting and then thinning at regular intervals — the greater sequestration intensity of juvenile trees can multiply the 100-ton average drawdown rate by orders of magnitude, and all that photosynthetic wealth can be turned to valuable, durable products.

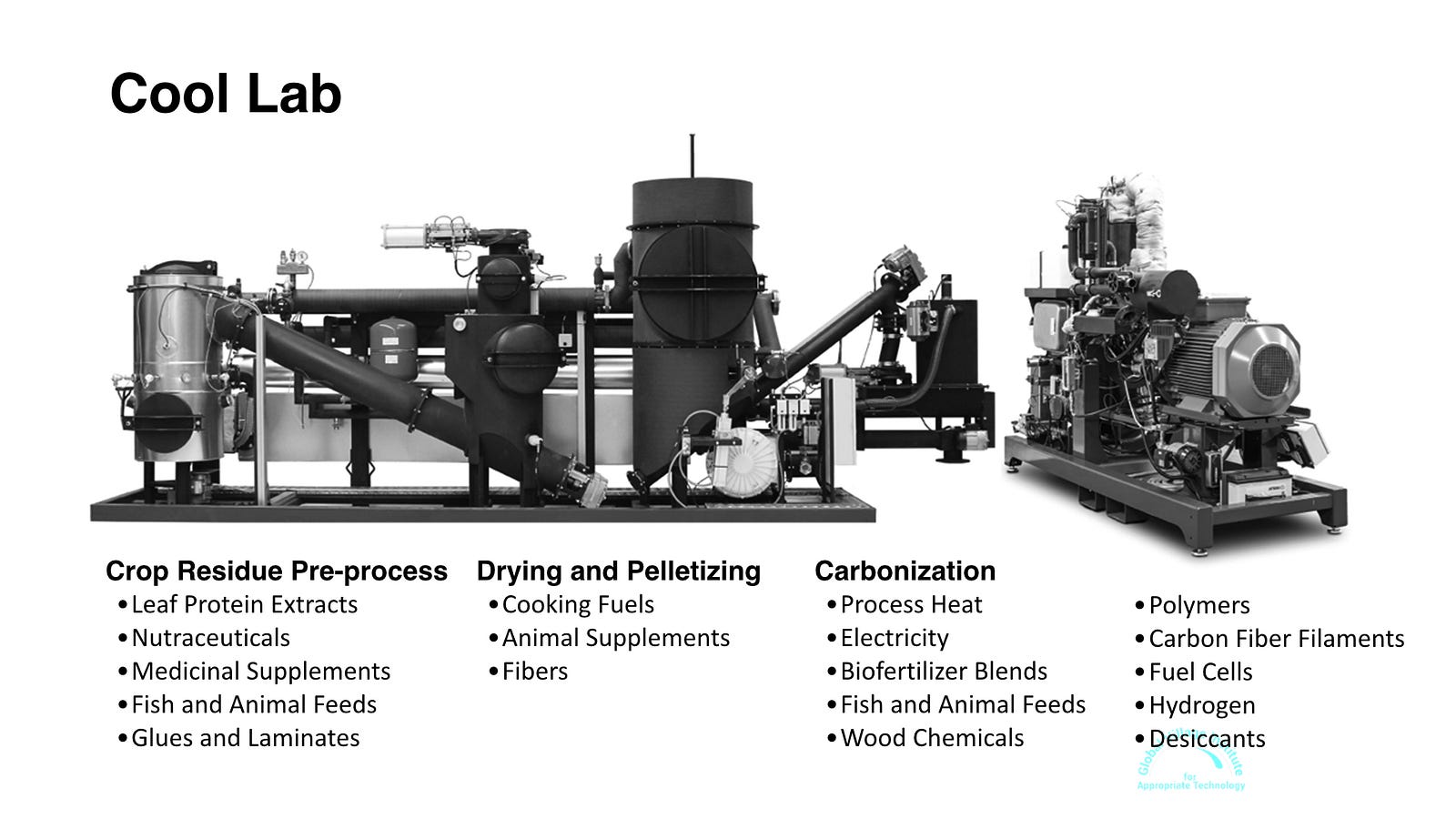

While it is possible BrewDog could be paid upwards of $100/ton for CO2 removal on a carbon exchange like Nori or Puro, more likely the aforementioned scheme of smallholder forested lots would generate far more income for rural Scotland by reviving lost crafts. Woodsmiths could build homes of timber and straw; fence and furnish them with coppiced poles and roundwood; heat and generate home power with firewood and pellets (using smokeless stoves like the Biolite, that produce both electricity and biochar); harvest fruit and nuts and process them; extract leaf proteins and medicinals; graze animals in the under-stories; and make biochar, bio-oils, and wood vinegar for fertilizers, mold-proof paints and plasters, insulation board, biocrete, polymers, electronic conductors and fuel cells, carbon fiber for 3D printers and structural wraps, water and whiskey filters, rubberizing compounds, lubricants, cattle-, aquaculture-, and poultry-probiotics, carbon black, graphene, and kitty litter. Brand all those new products BrewDog BioPunk. Build not only woodland homes, but homebrew Cool Labs.

This kind of distributed economic ramp compares favorably to BECCS (Biomass Energy with Carbon Capture and Removal), DACCS (Direct Air Carbon Capture and Removal — artificial trees), enhanced weathering (spreading rock dust), and other contrived, exotic CDRs which have yet to be proven at scale, cost $40-$1000/ton and likely will have significant impacts on water use, biodiversity, and other ecosystem health indicators.

The three most discussed means to accelerate CDR — (1) profitable products incorporating the removed carbon, (2) emissions-pricing policies like offset credit exchanges, and (3) government contracting at a scale that dwarfs the Manhattan or Apollo projects — all assume a stable world economy. In other words, they are prone to disruption in an era ravaged by the four horsemen of the Trumpocalypse:- Killer virus(es) on the loose;

- Economic collapse;

- Racial conflict and rioting; and

- Extreme weather.

Only a fourth possibility, CDR organized like the Scots’ forest smallholding system, with local cooperative structures meeting basic needs, is truly anti-fragile. The story could as easily be kelp forests in the tropics, rebuilding fish populations and coral reefs while softening hurricanes. Or it could be grasslands in Mongolia, holding back the desert while marketing salad bar yak.

Or the story could be beer brewers in Scotland, bringing back the trees of Caledonia while they sip their punk ale.

Help me get my blog posted every week. All Patreon donations and Blogger subscriptions are needed and welcomed. You are how we make this happen. Your contributions are being made to Global Village Institute, a tax-deductible 501(c)(3) charity. PowerUp! donors on Patreon get an autographed book off each first press run. My winter book, Dark Side of the Ocean, is shipping out now. My next book, Plagued, should be out in a few months. Please help if you can.

Comments