Horse on the Roof, Monkeys on the Pavement, Oh My!

"“They were falling out of the trees like apples”"

If the title wouldn’t have been too long I might also have included a line about dead people riding motorcycles. But read on.

Two weeks ago, I published a post, The Day After Next Week, about current weather records. That featured a picture of Caramelo, the horse in the area of south Brazil trapped for four days surrounded by floodwater, balancing on two strips of slippery asbestos roofing tile on a flooded farm building.

I am happy to report that firefighters and veterinarians sedated and immobilized the horse and strapped him into a Zodiac boat. The operation involved four inflatable boats and four support vessels and was carried live on television. Caramelo is doing fine.

Caramelo was one of about 10,000 rescued animals from that flood. 12,600 hogs and hundreds of thousands of poultry died. It rained 20 inches in just a few days, displacing more than 600,000 people. Not all made it to a roof.

The ongoing heat has also been roasting animals on land and in the water across southeast Asia. An estimated 40 people are dying each day in Myanmar. People are dying while riding motorcycles to desperately try to get cool.

A Smithsonian Institution dispatch from México tells us that howler monkeys are dying from dehydration and heatstroke and falling out of their trees. At least 138 howlers have been found dead in Tabasco since May 16.

In Burn: Using Fire to Cool the Earth (New Society, 2019), Kathleen Draper and I described a hopeful program in the tropical country of Belize, on the southern border of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. There, the Maya Mountain Research Farm has spent 40 years trying to recreate the syntropic, regenerative, eco-agroforestry patterns that sustained the ancient Maya for millennia, allowing them to survive at least three major climate change events and the Spanish conquest. Here is a brief excerpt:

After taking a Permaculture Design Course in 1991, Nesbitt dug swales across his hillsides and added a number of ground-hugging plants and vines to keep the soils shaded and protected from erosion. For him, cacao was the keystone plant in the system, and there was a good reason that the Maya placed a high social value on it, beyond its health and nutritional qualities. Cacao’s scientific name Theobroma means “food of the gods.”… When Mayan women go into labor they are given a big thick mug of toasted cacao, cane sugar and hot water. Because it is rich in calories and healthful, that big mug can see them through days of labor and the recovery afterward.

No green chlorophyllic cells can photosynthesize 100 percent of the sunlight that falls on an unfiltered square inch of ground in a day, so most of that solar energy is bounced back to space or lost to heat. Multistoried polyculture forests with climbing vines and groundcovers, on the other hand, share dappled rations of light as a community and have far greater absorption, production of oxygen, retention of nutrients, and a greater potential to provide food.

The Nesbitts’ near-term pioneer crops are annuals like corn and beans, or pineapple, pigeon pea, squash and melons planted between the corn contours, along with perennials like nopal cactus, yam, purslane, basil, amaranth and gourds. The intermediate crops are perennials like avocado, golden plum, zapote, sea almond, allspice, bamboo, palms, breadfruit, coconut, coffee, coco-yam, banana, citrus, mango, cacao, papaya, tea tree, euphorbia, noni, blackberries, gooseberry, chaya, ginger and pineapple. They will yield sweet fruits, jams, wines, basket-fiber, soaps, beverages and medicines after a few years of fast growth. The long-term crops are samwood, mahogany, cedar, teak, Malabar chestnut, sea chestnut and other slow-growing trees that will close the over-story.

An important feature to the tropical landscape design is the creation of soil. Here in the equatorial latitudes, much of the nutrient value of soils is carried in the standing plants, and the process of transmitting soil elements through decomposers and carriers to next year’s crops is very fast. The couple make a daily ritual of making biochar in a special gasifying stove they use to cook breadfruit. The biochar is mixed with animal manures and spread below the food trees, which then grow faster and fruit sooner.

Lately the Nesbitts have been thinking about how the small town just downriver is starting to outgrow its borders and infringe on the mixed-used forest and its traditional caretakers. He sees the possibility for strategic intervention. In 2017 the Nesbitts began working on a proposal for the Common Earth project being developed by the Commonwealth of Nations, of which Belize is a member. Common Earth wants to channel finance to worthy projects that focus on regenerative development to reverse climate change. Nesbitt’s plan is to contract with local forest smallholders to supply feedstocks to a Cool Lab, centrally located within the village, from the waste products of their milpas. They could also supply raw superfoods like cacao, coconut, vanilla, moringa, acai, goji berry, and blue-green algae for processing into high-value products.

The Nesbitts have a pretty good idea of where they might site a new village school and health clinic. With biomass-to-biochar energy and quick returns on investment they envision opportunities to offer gainful, antifragile employment to the youth of the village as they finish school and look for work. Given just a little assistance to get started, they will show Belize, the Commonwealth, and the world how it can be done.

On May 10, Christopher wrote:

Then, May 18, disaster struck. He had seen the smoke over the hills, and the orange glow on the horizon. He called to let us know that he expected the forefront to reach him within a few hours. It is usual practice in the tropics for farmers burn the corn stubble after harvest, but in recent years many new farms have pushed into forested areas and with the intense drought, burning has been banned. Still, unwary newbies and migrants from Guatemala or Honduras continue to burn. Since April wildfires have raged across the country. A permaculture food forester I know in a Mexican part of the Yucatán, Juan Carlos, wrote:

That night it came to Maya Mountain. Christopher said it was like Mordor. He and his neighbors came together to fight it. His permaculture design for the farm helped slow and divert the flames around the buildings and animal areas. Most of the mixed hardwood plantation was spared. Chris texted: “Also had four sheep born yesterday in the chaos, to make it all complete….” The lambs all survived.

In a Facebook post, Christopher wrote the following day:

The impact on wildlife behind us, the vast forest of the Columbia Forest Reserve, is unprecedented in Belizean history. The financial loss to farmers, especially cacao farmers, is in the millions of dollars. Over 200 farms destroyed, as of this afternoon. Fires still burning.

Just as it was sometimes hard to promote cacao when I managed Toledo Cacao Growers Association in the 1990s and 2000s because every year one or two farmers lost their cacao to an escaped agricultural fire, it's a hard sell to push agroforestry as a tool for climate change mitigation and adaption as well as food security when you have people who are either incapable of making good decisions, or who do not care enough about their neighbors to not light those fires. At least in those days it was one or two a year, if any. Literally hundreds of farmers have lost their farms to these fires in the last few weeks. If not for the heroic effort of the people who came to our farm, we would have lost our life's work, too.

I think the part that hurts Celini, and me, as well, is that people made a conscious decision to light agricultural fires in Toledo when we have had no rain since February. How do you make people understand that this is the hottest it has EVER been in Belize, and that this may be the new normal as we walk blithely towards hothouse Earth? How do you communicate where we are as a species to people who are uninformed or ideologically committed to saying climate change is not real, or simply chose to pretend this is normal?

For once in my life, I have very little optimism that we as a species can turn this around because there are people who can light fires on an already burning planet. Feeling deeply disheartened and sympathy for the many, many, many farmers whose farms were destroyed by these fires. Hoping that there will be lasting solutions to this problem implemented both bottom up by farmers and top down by Government of Belize.

Please buoy Celini in love and support. Be kind. We all live on one planet.

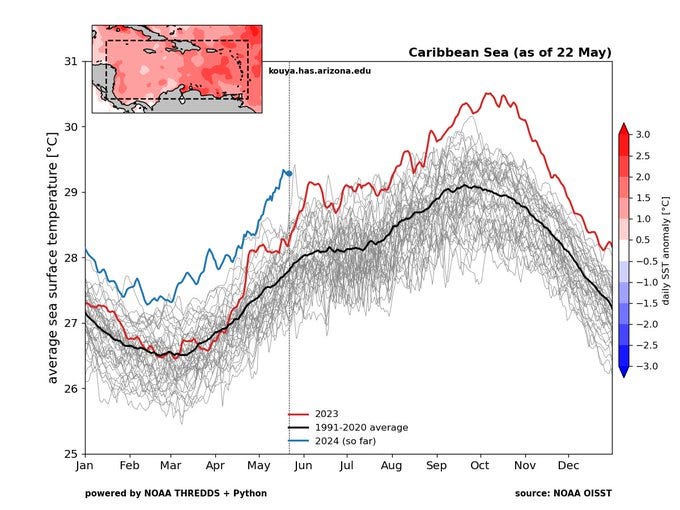

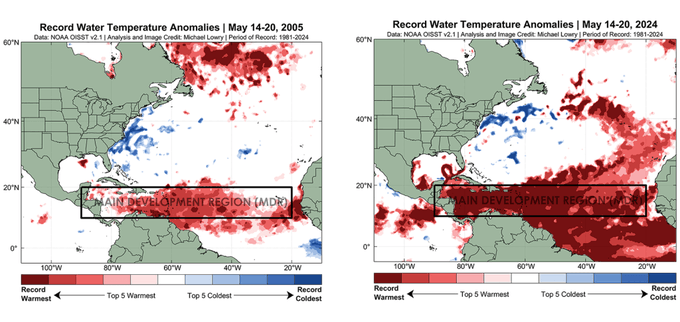

Of course, nowhere is safe now. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issued its strongest warning for Atlantic hurricanes this year due to the unprecedented surface temperatures in the area that hurricanes form that extend from West Africa to the Western Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico.

At the same time, hundreds of millions of Indians and Chinese are enduring record heat waves.

— The New York Times

Around the world, the accumulated losses from drenching thunderstorms are approaching those from hurricanes. The reason: Warmer air holds more moisture, which means there is more water vapor in the sky that can form clouds. The heat energy released into the atmosphere by this condensation is what feeds thunderstorms. More heat, stronger storms. Concentrated bursts can also produce strong winds that fan out in wide lines rather than follow more confined, circuitous paths like twisters. We saw this earlier this month in Texas.

— CBC

It is a vicious feedback loop. More condensation of water vapor also means less solar radiation leaving than coming in, leading to a build-up of heat due to the greenhouse effect.

We all live on one planet.

More trees, like they plant at Maya Mountain, would help. Rob de Laet at the EcoRestoration Alliance writes:

Clouds rise up to 15 km high, particularly in the tropics, transporting all that heat up and out. Deforestation has reduced this kind of cloud formation, which normally helps release latent heat as clouds form at higher altitudes. This heat partly leaves the atmosphere through the atmospheric window and partly warms the air at the tropopauze level and is carried away by the jet stream, eventually radiating out to space.

The total latent heat energy released from the Amazon can be calculated from its annual precipitation (2.25 meters per year on average). More forest area means more heat transport from the surface, combined with the effects of the biotic pump and cloud reflectivity (12%, based on McIlveen, we estimated it independently as slightly higher at 17%). Restoring rainforests to their size from 50 years ago would increase the flow of long-wave radiation to space, counteracting the enhanced greenhouse effect from CO2 and other gases and improving the EEI considerably through the combined cooling effects. Hence our calculation that converting 280 million hectares of open/degraded lands in the tropics to forest or multi-layered agroforestry would ''stand-alone'' cool the planet by almost 1 degree centigrade.

I’d like to end on a hopeful note, but I confess, it keeps getting harder to do that. One thing that my readers can do that would be hopeful would be to help me help Christopher and Celini replant their vanilla vines.

I have taken down the paywall on this post this week. I will skip our usual pitch to help refugees from war zones reach safety, although that campaign continues, and make this pitch instead. If you would like to help the Maya Mountain Research Farm recover from the fire and continue to demonstrate the best way to adapt to climate chaos while also reversing it, using indigenous ancient wisdom, please contribute here: https://gofund.me/741758d4

References:

Bates, Albert, and Kathleen Draper. Burn: Igniting a New Carbon Drawdown Economy to End the Climate Crisis. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2020.

Ellison, David, Jan Pokorný, and Martin Wild. "Even cooler insights: On the power of forests to (water the Earth and) cool the planet." Global change biology 30.2 (2024): e17195.

Ford, Anabel, and Ronald Nigh. "Origins of the Maya forest garden: Maya resource management." Journal of Ethnobiology 29.2 (2009): 213-236.

Ford, Anabel, and Ronald Nigh. The Maya forest garden: Eight millennia of sustainable cultivation of the tropical woodlands. Vol. 6. Routledge, 2016.

Ford, Anabel. "The Milpa Cycle as a Sustainable Ecological Resource." Climatic and Ecological Change in the Americas (2023): 34.

Loeb NG, Johnson GC, Thorsen TJ et al. Satellite and ocean data reveal marked increase in Earth’s heating rate. Geophys Res Lett 2021;48:e2021GL093047.

McIlveen, Robin. Fundamentals of weather and climate. Psychology Press, 1998.

Comments